I was not entirely surprised by Peter Beinart’s recent disavowal of the two-state solution and his advocacy of a binational state or a confederation of states in place of Israel.

The left-leaning, iconoclastic American Jewish writer and political activist long ago broke with the dogma that Jews are obliged to support Israel whether it is right or wrong in its policy decisions. Now he has gone even further, much to the dismay of Jews who feel a deep attachment to Israel.

As he wrote in “I No Longer Believe in a Jewish State,” an op-ed piece published in The New York Times on July 8, “It’s time to abandon the traditional two-state solution and embrace the goal of equal rights for Jews and Palestinians. It’s time to imagine a Jewish home that is not a Jewish state.”

In a much longer version in the left-wing American Jewish magazine Jewish Currents, Beinart wrote, “The painful truth is that the project to which liberal Zionists like myself have devoted ourselves for decades — a state for Palestinians separated from a state for Jews — has failed. The traditional two-state solution no longer offers a compelling alternative to Israel’s current path. It risks becoming, instead, a way of camouflaging and enabling that path. It is time for liberal Zionists to abandon the goal of Jewish–Palestinian separation and embrace the goal of Jewish–Palestinian equality.”

Beinart, a progressive Jew, believes that his plan to untangle the maddeningly complex and protracted conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is a clarion call for peace and stability after so much strife and violence.

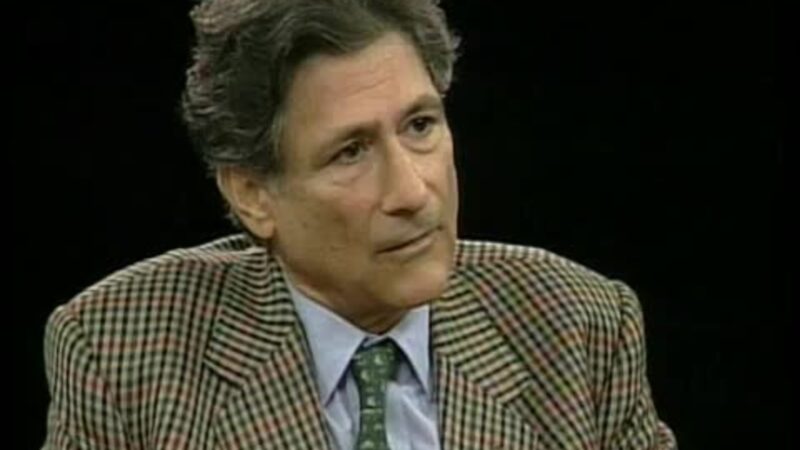

But to his critics, it is repugnant, utopian and unrealistic, a scheme promoted by Palestinian nationalists such as the late Edward Said, radical Arab nationalist regimes like Syria, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, which rejects Israel’s existence altogether.

In short, it is designed to upend the two-state formula, which has earned international acceptance and legitimacy, and by implication to dismantle Israel as a Jewish state underpinned by Zionist values.

Oddly enough, it mirrors the British government’s 1917 Balfour Declaration, which endorsed the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” in what was then Palestine.

Contrary to what Beinart’s detractors may claim, I don’t believe he identifies with Israel’s enemies or wishes them well. And he is not a “traitor,” an accusation that will surely be hurled at him by Jews on the right. But let’s face the unvarnished truth. Israel’s arch foes will jump on Beinart’s bandwagon with glee and feel emboldened by his sharp departure from conventional thinking.

To anyone familiar with his views, Beinart’s new position is hardly surprising. He’s a person who goes against the grain.

A decade ago, in a thought-provoking piece in the New York Review of Books, he correctly observed that Israel’s acquisition of territories captured during the 1967 Six Day War had produced a sense of hubris in the Israeli leadership and sharply turned Israel rightward. Palestinian suicide attacks from the mid-1990s onward only hardened the suspicions of Israelis about Palestinian intensions.

As Beinart noted, Jewish liberals were particularly alienated by Israel’s settlement project in the occupied areas and by Israel’s stubborn resistance to Palestinian statehood.

With an eye on the United States, Beinart wrote, “For several decades, the Jewish Establishment has asked American Jews to check their liberalism at Zionism’s door, and now, to their horror, they are finding that many young Jews have checked their Zionism instead.”

Although Beinart was increasingly disillusioned by Israel’s rigid stance toward the Palestinians, he stayed loyal to Zionism, which demanded a Jewish state as a necessity after the unprecedented horrors of the Holocaust.

As he told the General Assembly of Jewish Federations in 2011, “I want Israel to remain a Jewish state for my children and grandchildren as much as anyone in this room.” But he added an important caveat. For Israel to be a legitimate state, it would have to offer “citizenship to everybody in its borders, irrespective of race, religion, sex and ethnicity.”

This has not happened, of course.

Israel’s nearly two million Palestinian Arab citizens, representing 20 percent of its population, enjoy equal rights with Jews in theory. But in practice, they are second-class citizens concerning the allocation of municipal budgets, employment opportunities, and access to housing in Jewish villages, towns and cities.

The 2.5 million Palestinians of the Israeli-occupied West Bank are much worse off, having been subjected to draconian regulations since the first and second Palestinian uprisings. These revolts broke out in 1987 and 2000 and were accompanied by a wave of terrorism. As a result, Israel tightened security drastically, and now Palestinians are forced to pass through a maze of checkpoints and cannot move around freely.

Nor are the Palestinians eligible for Israeli citizenship or the right to vote in Israel’s general elections. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu confirmed this recently in comments he made about Palestinians who will live in Israeli-annexed areas of the West Bank.

The issue of annexation notwithstanding, Israel’s 53-year occupation of the West Bank presents huge problems for its future as a democratic Jewish state.

If the Palestinians of the West Bank are granted citizenship, they would soon form a majority of Israel’s population, thereby pushing Israel ever closer to binational status, a sharp step away from the goals of Zionism. But if the Palestinians are denied democratic civil rights, which is currently the case, Israel will drift into the treacherous waters of apartheid.

In the meantime, Israel has deliberately divided the West Bank into a patchwork of non-contiguous enclaves, which, in turn, are broken up by Israeli roads, army camps and shooting ranges.

Under the terms of the second Oslo agreement in 1995, Palestinians exercise full control of only a small chunk of the West Bank, Area A, the location of their major towns. In Area B, the Palestinian Authority wields civil power, but Israel is in charge of security. Israel retains 60 percent of the West Bank in Area C, where its array of settlements and outposts are found.

Even if Israel were to relinquish every square foot of the West Bank, which constitutes part of the ancestral homeland of the Jewish people, the Palestinians would receive only about 22 percent of pre-1948 Palestine. But let’s be clear: the current right-wing Israeli government has no intention whatsoever of ceding the whole of the West Bank to the Palestinians.

By the terms of U.S. President Donald Trump’s peace plan, the Palestinians would be handed 70 percent of the West Bank, but only under severe conditions. Yet even this ineffectual proposal is unacceptable to Netanyahu’s Zionist Revisionist government, which regards real Palestinian statehood as a non-starter and a dire threat to Israel’s existence.

Given these harsh realities, Beinart concluded that a two-state solution was passe and irrelevant and should be replaced with a far different model.

Justifying his rejection of Jewish statehood, he wrote in Jewish Currents, “This doesn’t require abandoning Zionism. It requires reviving an understanding of it that has largely been forgotten. It requires distinguishing between form and essence. The essence of Zionism is not a Jewish state in the land of Israel; it is a Jewish home in the land of Israel, a thriving Jewish society that both offers Jews refuge and enriches the entire Jewish world. It’s time to explore other ways to achieve that goal — from confederation to a democratic binational state — that don’t require subjugating another people. It’s time to envision a Jewish home that is a Palestinian home, too.

“The two-state solution — which has come to mean a fragmented Palestine under de facto Israeli control — cannot do that. It no longer provides hope.”

Writing in The New York Times, he said, “I knew Israel was wrong to deny Palestinians in the West Bank citizenship, due process, free movement and the right to vote in the country in which they lived. But the dream of a two-state solution that would give Palestinians a country of their own let me hope that I could remain a liberal and a supporter of Jewish statehood at the same time.

“Events have now extinguished that hope. About 640,000 Jewish settlers now live in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, and the Israeli and American governments have divested Palestinian statehood of any real meaning. The Trump administration’s peace plan envisions an archipelago of Palestinian towns, scattered across as little as 70 percent of the West Bank, under Israeli control. Even the leaders of Israel’s supposedly center-left parties don’t support a viable, sovereign Palestinian state.

“If Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu fulfills his pledge to impose Israeli sovereignty in parts of the West Bank, he will just formalize a decades-old reality: In practice, Israel annexed the West Bank long ago.

“Israel has all but made its decision: one country that includes millions of Palestinians who lack basic rights. Now liberal Zionists must make our decision, too. It’s time to abandon the traditional two-state solution and embrace the goal of equal rights for Jews and Palestinians. It’s time to imagine a Jewish home that is not a Jewish state.

“A Jewish state has become the dominant form of Zionism. But it is not the essence of Zionism. The essence of Zionism is a Jewish home in the land of Israel, a thriving Jewish society that can provide refuge and rejuvenation for Jews across the world.”

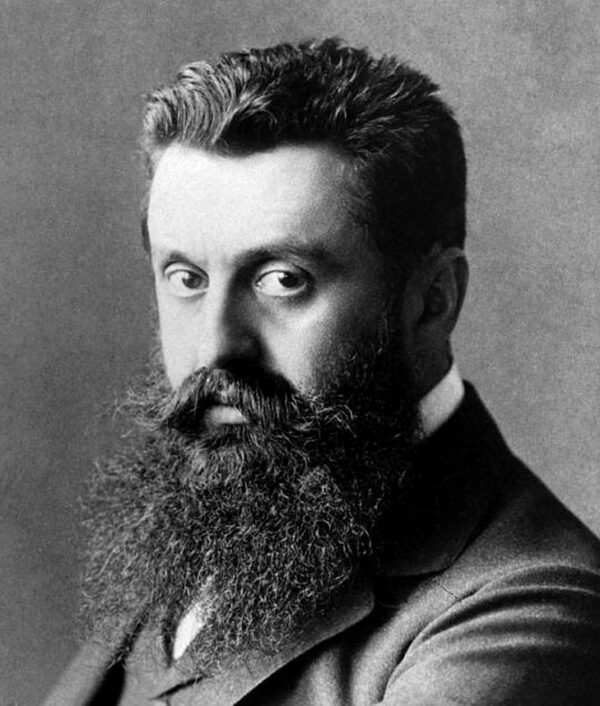

Beinart’s assumption that statehood was not the overriding aim of Zionism is historically incorrect. A minority of Zionists, coalescing around Ahad Ha’am and later Judah Magnes, were infinitely more interested in a spiritual homeland than in a full-blown state. But Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, envisaged Jewish statehood as its cardinal objective.

Certainly, David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, never wavered from his belief that statehood, even on a smaller territorial scale as defined by the United Nations 1947 Palestine partition plan, was absolutely necessary.

Rarely, if ever, did he and his colleagues seriously contemplate a binational state. Binationalism was not only unpopular among Palestinian Jews, but among Palestinian Arabs, who hungered for an independent Arab state.

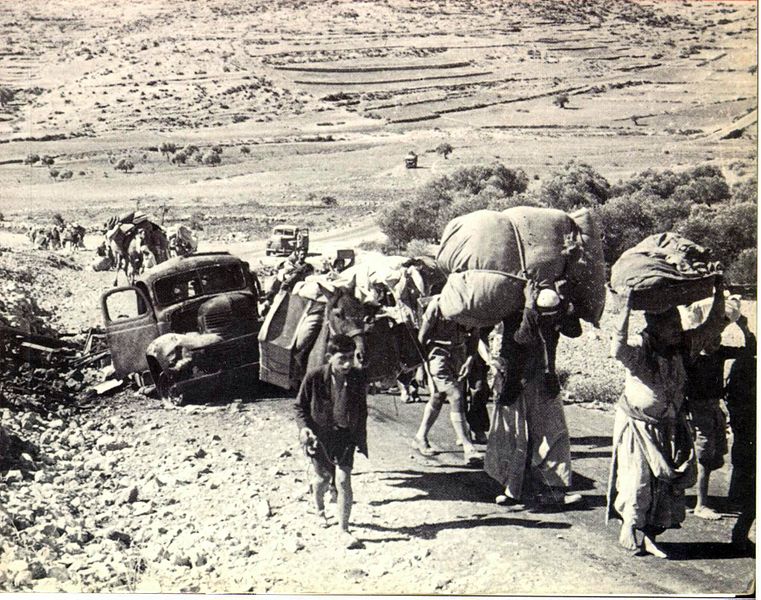

Before the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, precious few Palestinian leaders were even willing to discuss the notion of a binational state or a confederation. They were confident that their side would prevail in an armed confrontation with the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine.

In 1937, the journalist Arthur Koestler, having travelled to Palestine on assignment, expressed the view that, for all intents and purposes, partition already had occurred. “The two communities seem to live on different planets,” he wrote, adding that Palestinian Arabs sought “a state with, to be blunt, as few Jews as possible.”

The Jews of Palestine, he said, had created a self-governing entity with its own economy, political parties, cultural institutions, labor unions and medical system.

By no coincidence, the 1937 Peel Commission recommended partition as the best possible solution under the circumstances. As its report stated, “There is no common ground between (Jews and Arabs). Their national aspirations are incompatible.”

Once hostilities erupted in 1947, the Palestinian military commander Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini declared, “It is inconceivable that Palestine will be for the Arabs and the Zionists together. It’s us or them.”

Israel is a strong and prosperous nation today, its internal and external problems notwithstanding, and the idea that Israeli Jews would voluntarily surrender their hard-won sovereignty and independence for the sake of a binational state, or a confederation, is a grand illusion and a pipe dream.

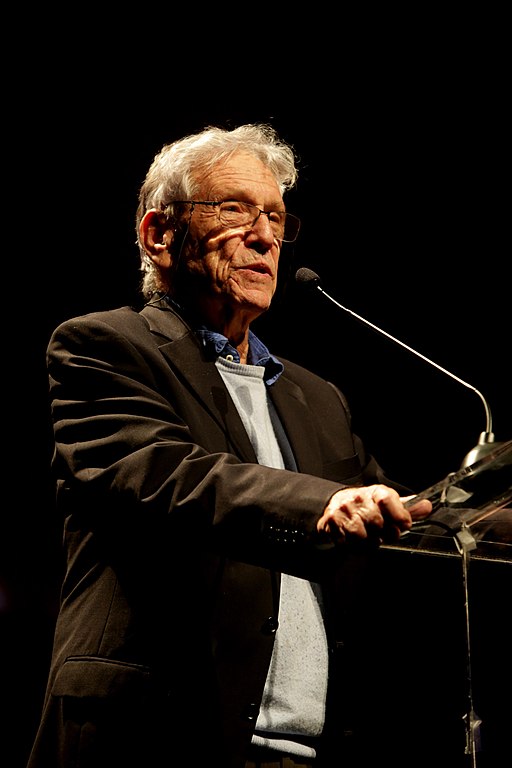

The late Israeli novelist Amos Oz, a dove who supported a two-state solution, dismissed that notion as “a sad joke.” As he said, “You can’t expect Israelis and Palestinians after 100 years of blood, tears and calamity to jump into a double bed and begin their honeymoon.”

He is absolutely right.

The surfeit of mutual Israeli-Palestinian animosity after more than a century of conflict means that Beinart’s idealistic solution cannot seriously be considered, much less implemented. It is neither practical nor doable. No less a person than the staunchly anti-Zionist academic Maxime Robinson dismissed the binational alternative as unrealistic. “One can speak only in terms of the coexistence of two states,” he said.

And there is something else to ponder. A binational state, given the imperatives of demography, would eventually morph into a majority Arab/Muslim state in which Jews would be a tolerated minority with religious rights.

There are something like 55 Muslim states in the world today. Surely Jews are entitled to one state. Is this too much to ask?

Although Beinart’s prescription for peace is far-fetched, his basic critique of Israeli policy is spot on. Israel’s occupation of the West Bank is morally unjustifiable and politically indefensible and untenable. The Palestinians need and deserve statehood, but this is an outcome that must be achieved through the framework of sincere and patient negotiations.

The current Israeli government, as well as some factions of the Palestinian national movement, have no interest in a fair and equitable process. But Israelis and Palestinians of goodwill are free to pursue this admirable yet elusive objective.

I’m convinced that Beinart’s motives in advocating a binational state, or a confederation, are well-meant. But he is heading down the wrong road.

A two-state solution, though battered and bruised by setbacks, is still possible if both sides are prepared to leave the past behind and make far-reaching historic territorial compromises.

I don’t expect this scenario to unfold any time soon, or even ever. But it has a far better chance of materializing than Beinart’s dreamy proposal.