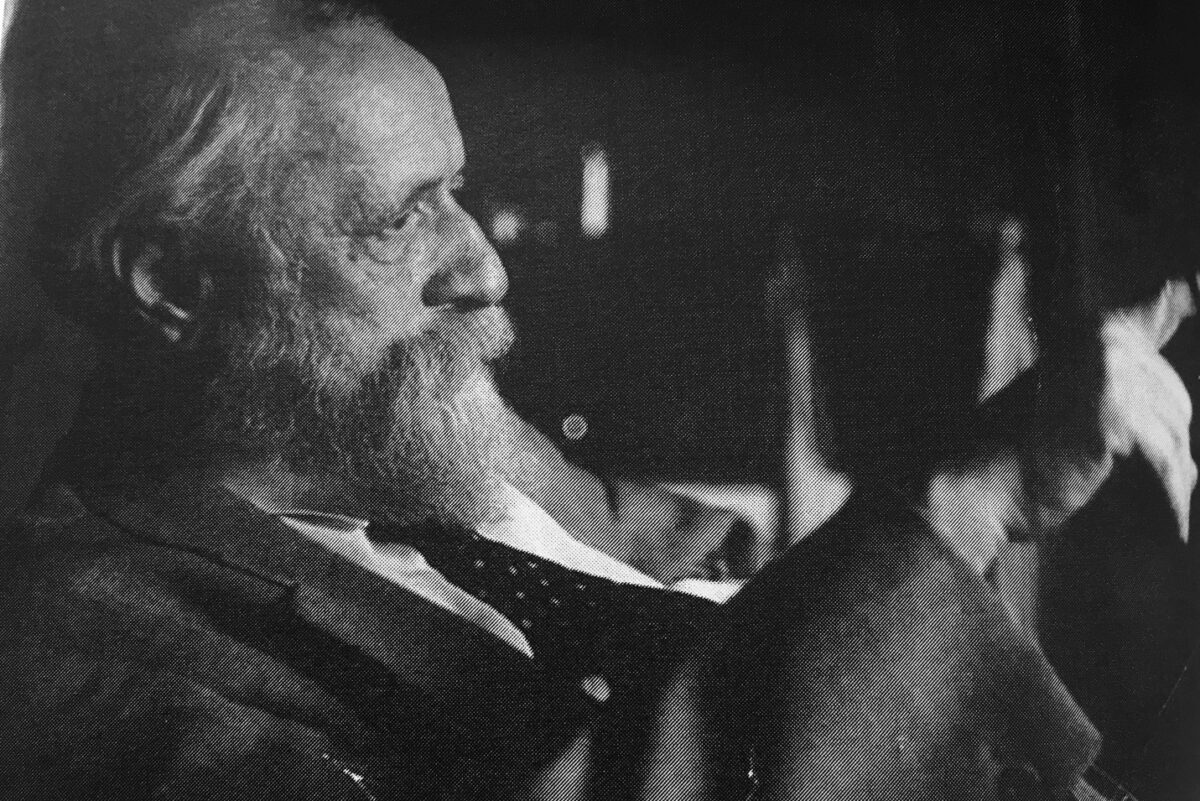

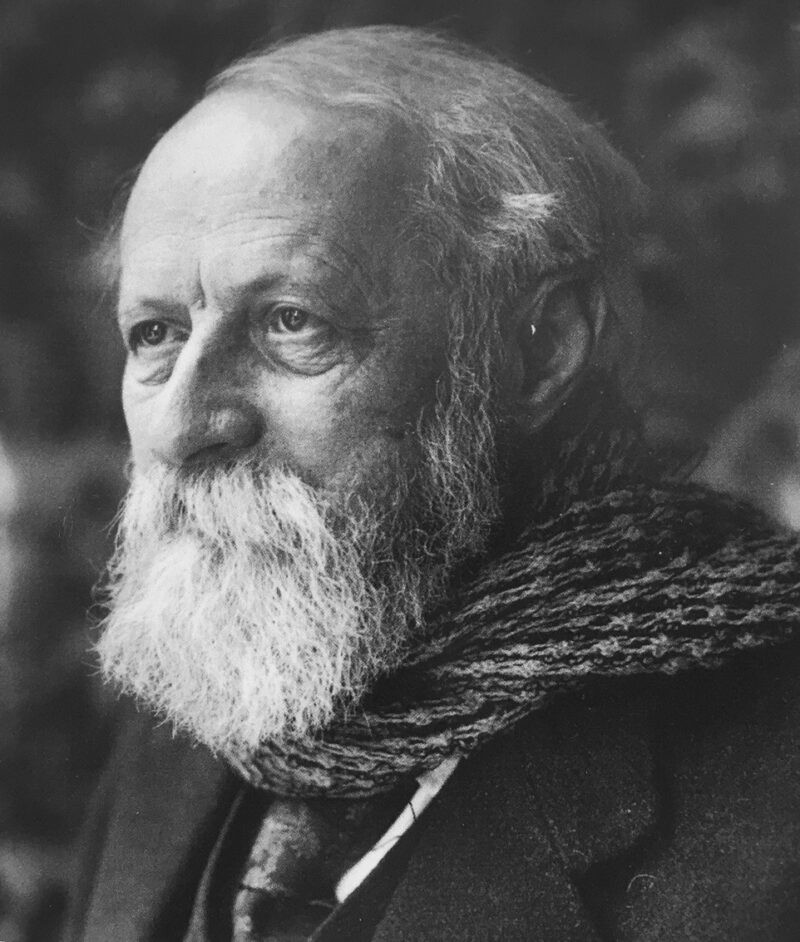

The philosopher Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a towering figure in academia, an interpreter of Jewish mysticism and Hassidism, and a dissident figure in the Zionist movement.

The first major biography in English of this seminal German-Jewish thinker in more than three decades has been published. It is written by Paul Mendes-Flohr, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the editor of a 22-volume set of Buber’s collected works.

Martin Buber: A Life of Faith and Dissent is the latest volume in Yale University Press’ Jewish Lives series. Mendes-Flohr, in meticulous fashion and with erudition, explores his childhood, academic career and complex relationship with Zionism. These topics are far more accessible for the average reader than his forays into the dense thickets of Buber’s philosophical theories.

Born in Vienna, Buber suffered a traumatic loss at the tender age of three when his parents, Carl and Elise, suddenly separated. His mother had an affair with a Russian army officer and left the family dwelling without even bidding farewell to her son. Her disappearance affected him profoundly. In early love letters to Paula Winkler, his future wife, he raised the possibility that she could be his surrogate mother.

His father, being unable or unwilling to care for him, sent Buber to Lemberg, since renamed Lwow, to live with his paternal grandparents, Salomon and Adele, a wealthy and cultivated couple who would raise him until he was 14.

Home schooled until 10, he receiving private lessons in German, English, French and traditional Jewish subjects. His observant and learned grandfather taught him Hebrew and the fundamentals of Judaism. His teacher in rabbinic literature was his great uncle. Buber credited his grandmother with having introduced him to books and reading and to spoken German.

As a young man, he grew a beard to cover up a twisted lower lip, an injury caused during his birth.

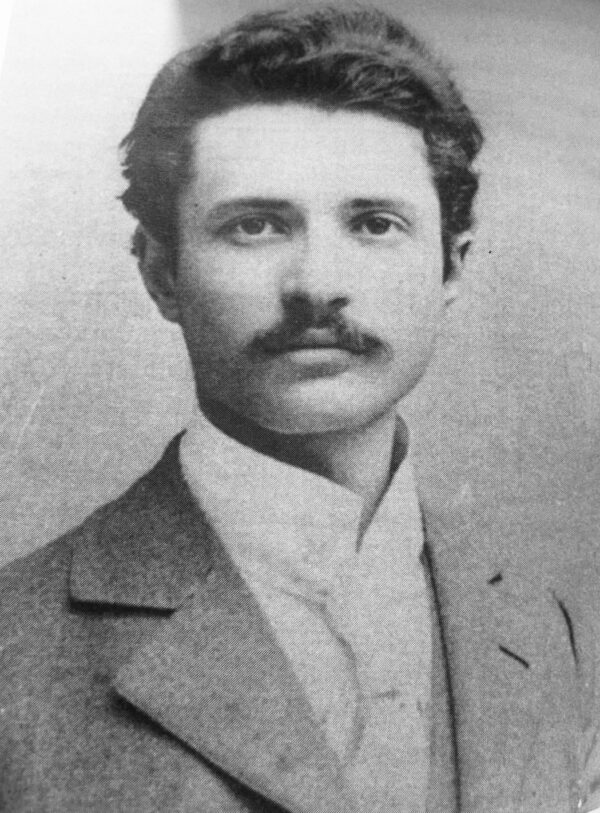

He met Winkler, a German Catholic from Munich, at the University of Zurich in the autumn of 1899. One of the very few female students on campus, she was vivacious, bohemian and intellectually engaged. She gave birth to his two children in 1900 and 1901. Winkler married Buber in 1907, a year after converting to Judaism.

A published novelist in her own right, she was a tremendous helpmate, supporting his growing interest in Zionism and serving as his consultant in German grammar and style. “Martin found in Paula not only the mother figure he longed for, but also a soulmate,” writes Mendes-Flohr, adding that they were bound together by romantic love and intellectual and spiritual compatibility.

Thanks to her encouragement, Buber plunged into a serious study of Hassidism, a gateway to knowledge of the underlying spiritual foundations of Judaism. “Buber’s early representations of Hassidism were primed by a desire to counter the negative views of Eastern European Jewry,” says Mendes-Flohr.

Buber’s quest to improve the image of Eastern European Jews was rooted in his love of Yiddish, the common language of the so-called Ostjuden. In 1902, he and several Polish Jews founded a journal that reprinted Yiddish and Hebrew poems in German by poets ranging from Hayim Nachman Bialik to Sholem Asch.

A year before assuming this position, Buber was appointed editor-in-chief of Die Welt, a Zionist weekly, by Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism. According to Mendes-Flohr, Herzl was impressed by his charismatic personality and oratorical skills. When the pair had a falling out, Buber withdrew from Zionist affairs.

This was hardly surprising. A cultural Zionist who rejected the goal of Jewish political sovereignty in Palestine, Buber was distrustful of the nation-state and feared that Zionism might degenerate into what Mendes-Flohr describes as “unalloyed political nationalism.” Consequently, he opposed the Balfour Declaration, issued by the British government in 1917.

“Buber was well aware that he was swimming against the current, and that his jeremiad against political nationalism would be dismissed as hopelessly detached from the brutal realities faced by the Jewish people,” says Mendes-Flohr.

On the eve of the Nazi takeover of Germany, Buber was comfortably ensconced as a professor at the University of Frankfurt and confident that the Nazis could be held at bay. “He clung to the belief that the devotees of the German humanistic tradition would rally their fellow citizens to resist the allure of Hitler’s diabolical nationalism,” says Mendes-Flohr.

His wife, however, was not as sanguine, fearing that even decent and upright Germans would be sucked into the vortex of Nazism.

In the autumn of 1933, a pack of Brownshirts — the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party — marched through Heppenheim, where the Bubers lived, and stopped in front of their home in a none too subtle gesture of intimidation. A week later, following the passage of a law barring Jews from holding jobs in government institutions, Buber resigned his professorship. In 1935, the Gestapo issued an order forbidding him to deliver public and private lectures. It was partially rescinded several months later.

Having been offered a professorship in religious studies at the Hebrew University, Buber immigrated to Palestine in March 1938, just months before the outbreak of Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogroms which spelled finis to Germany’s Jewish community.

He left the country with a heavy heart, unsure whether he could learn Hebrew sufficiently well. Prior to his departure, he had studied modern Hebrew. Once in Jerusalem, he took lessons in colloquial Hebrew, which, more or less, he mastered.

He and his family faced financial difficulties in British Mandate Palestine. The Nazis had imposed a 25 percent tax on his assets, while the Polish government blocked his access to his father’s inheritance. Buber’s financial position improved after World War II, when many of his books, including I and Thou, were translated into English and sold in the United States.

Much to his sorrow and disgust, he learned that his home in Heppenheim had been plundered and that much of his library had been destroyed during Kristallnacht.

Being lukewarm to Jewish statehood, Buber joined Brit Shalom, an organization advocating a binational state in Palestine. Two weeks into the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, he wrote an article bemoaning the Zionist pursuit of a Jewish state at any cost.

The war upended the Bubers’ lives. With Iraqi troops converging on Abu-Tor, a largely Palestinian neighborhood in which they resided, the Bubers were forced to vacate their apartment. Their possessions and library remained untouched, their Palestinian landlord having placed them in a locked room for safekeeping.

After the war, the Bubers moved into a large and comfortable house in Talbiya owned by a Palestinian who had fled to Turkey. He was uneasy about living in the former residence of an Arab family. “Buber’s response was to conduct a determined campaign to allow the (Palestinian) refugees to return to their homes or receive proper compensation, which led to a clash with David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel,” says Mendes-Flohr.

Like some Jews who had been forced out of Germany, Buber refused to set foot there in the wake of the war. But he was eager to resume his publications in German. Buber was a prolific writer, judging by the avalanche of books, articles and letters he churned out, yet writing exacted “a terrible strain” on him.

In 1950, Buber had a change of heart and returned to Germany, where he delivered a lecture in Heidelberg. He would return many more times. In 1957, he met the philosopher Martin Heidegger, a former Nazi, in Germany.

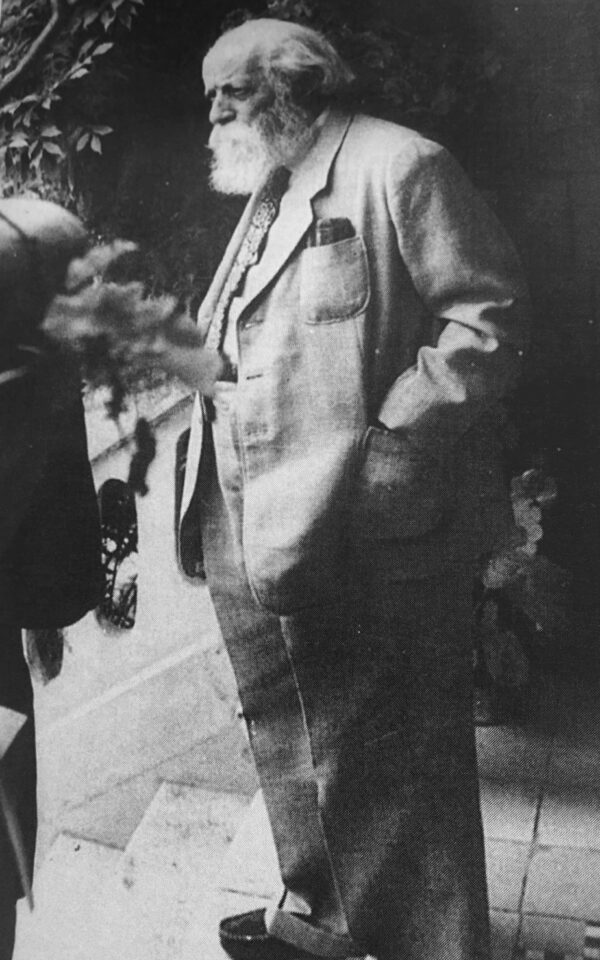

During the postwar period, he received a succession of honorary doctorates from European universities. In Israel, he remained something of an outsider, his unpopular views on the Arab-Israeli dispute having alienated some Israelis. Eventually, he received a measure of public recognition in Israel. He was awarded the Israel Prize for the Humanities in 1953 in a ceremony presided over by Ben-Gurion. In 1961, he was the recipient of Tel Aviv’s Bialik Prize for contributions to Jewish studies.

Buber was an iconoclast until the end. He expressed dissatisfaction with Israel’s treatment of Israeli Arabs. And after the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann was sentenced to death, he signed a petition to commute his sentence, claiming that Eichmann should have been tried in an international court.

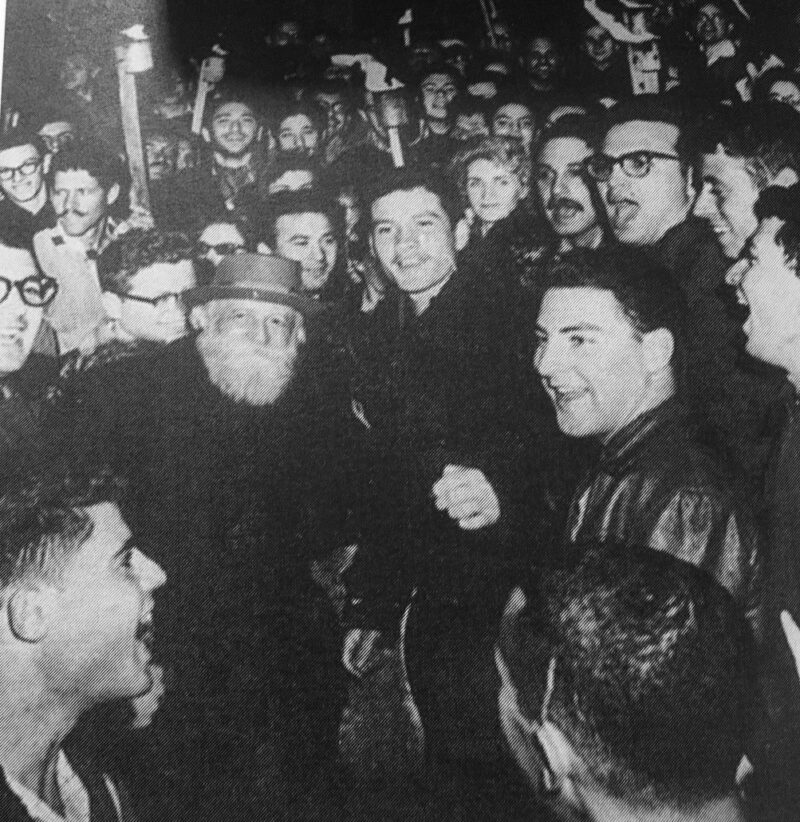

As Buber approached his 85th birthday, he was honored as one of the founding fathers of Zionism. In an ambivalent note of praise, Ben-Gurion sent him a cable saying, “I honor and oppose you.”

Buber died on June 13, 1965, prompting Ben-Gurion to eulogize his passing as “a great loss to the country’s spiritual life.” Ben-Gurion’s successor, Levi Eshkol, paid him a high compliment, calling Buber “the most distinguished representative of the Jewish people’s reborn spirit.”

Much to his credit, Mendes-Flohr skillfully distills the essence of of this great man’s life in this stimulating book.