Max Steiner practically created the language of Hollywood movie music. In a career encompassing some 300 films, he composed and orchestrated scores that riveted hearts and minds.

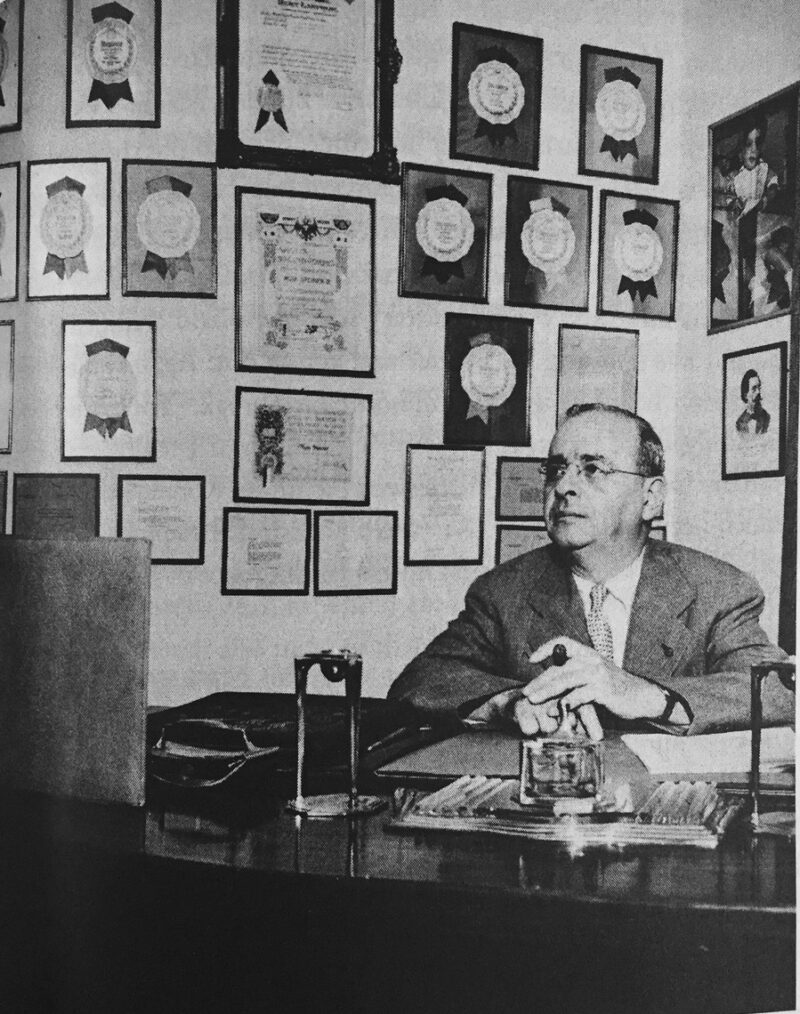

The recipient of 24 Oscar nominations and the winner of three Academy Awards who established background music as a crucial element in motion pictures, he worked with such luminaries as the producer David O. Selznick, the director Frank Capra, the composer Irving Berlin and the actress Bette Davis.

A master of the paradoxical art of film scoring, Steiner’s music “managed to be at once unobtrusive and indispensable and has thus survived the decades,” writes Steven C. Smith in his lively book, Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer, published by Oxford University Press.

A composer, arranger and conductor whose scores amplified the psychology of characters, portended bombshells and heightened climaxes, Steiner was involved in a procession of memorable movies: King Kong, The Charge of the Light Brigade, Jezebel, Gone with the Wind, Casablanca, The Big Sleep, Key Largo, and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

As Smith says, he was “one of the undisputed titans” in his industry. “He would do more than any other composer to invent and codify film scoring as we know it today.”

A Viennese Jew born in 1888, he arrived in Hollywood in 1929 as an orchestrator. Due to his inexhaustible gift for melody, his capacity for hard work and his reputation for reliability, he swiftly became its highest-paid, most honored composer.

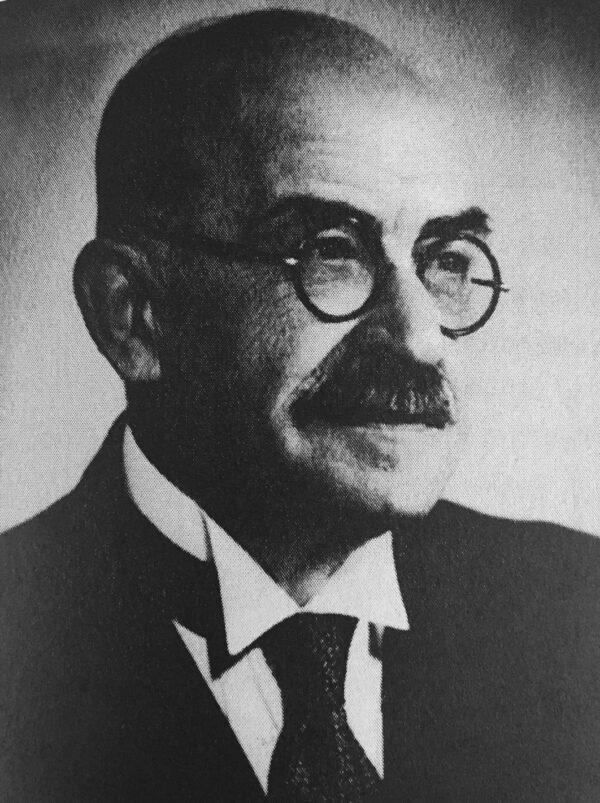

Steiner’s destiny was virtually preordained, his father, uncle and grandfather having managed several of Vienna’s most important musical theatres. The upsurge of antisemitism in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th century prompted his father, Gabor, to convert to Christianity in 1894. Steiner, baptized in a Protestant church in the same year, considered himself a Christian.

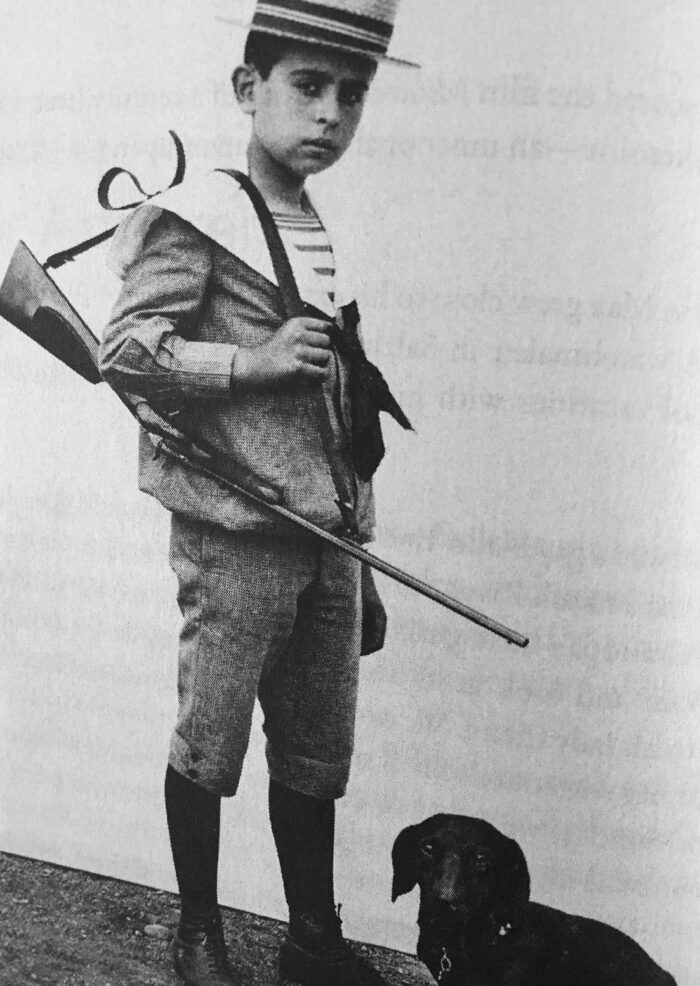

Under his father’s influence, he published his first song, Let Me Kiss You One More Time, at the age of nine. A fan of Richard Strauss’ waltzes and operettas, he studied counterpoint and harmony, mastered the piano and learned to play the organ, trumpet and trombone. His first operetta, The Beautiful Greek Girl, premiered in 1907.

He immigrated to Britain in the following year, convinced that his job prospects would be better in London. He had another reason for leaving Vienna. He had fallen in love with a British singer and dancer. She would be the first of four wives.

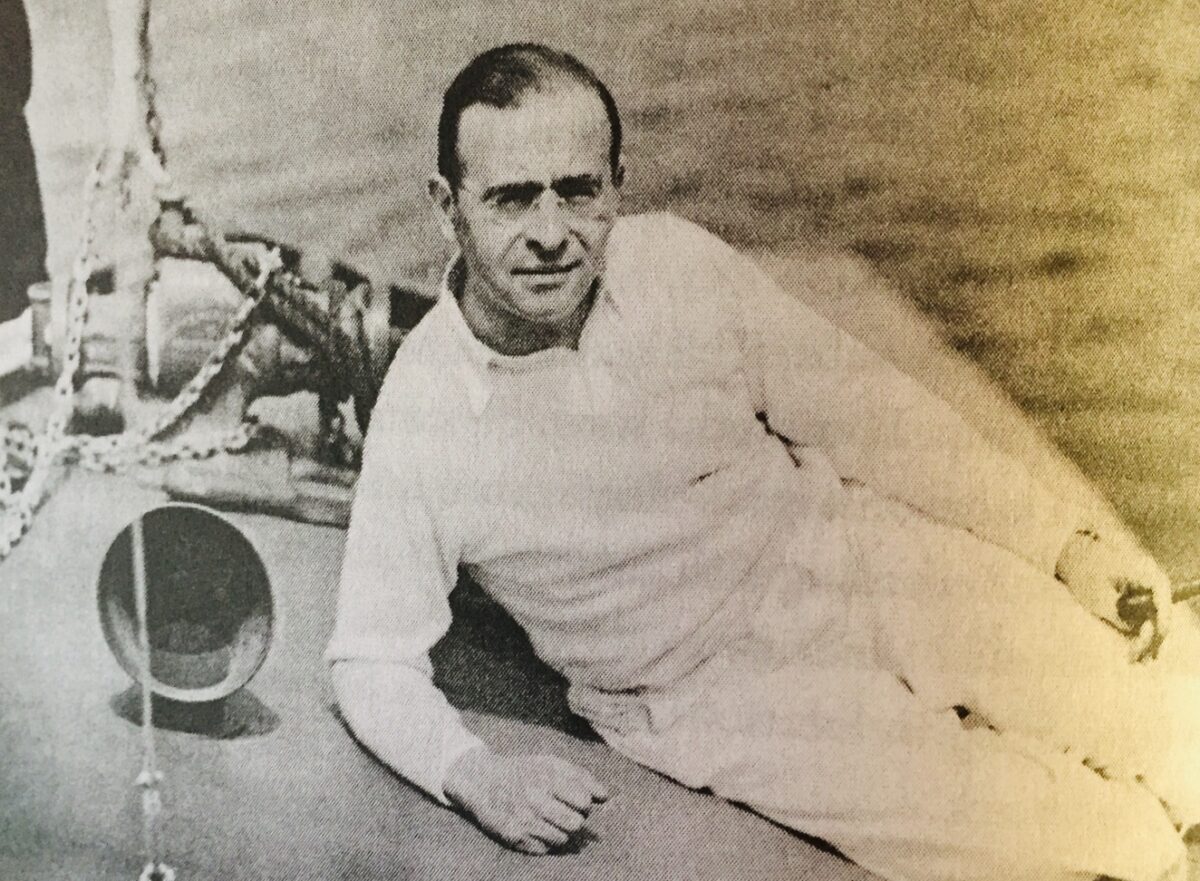

Steiner was moderately successful as a musical director in London, but when he learned he would be classified as an enemy alien following the outbreak in World War I in 1914, he left Britain. He arrived at New York City’s Ellis Island in November of that fateful year, and soon found work as a musician.

He was seldom jobless. Among the people he worked with was the celebrated American composer Victor Herbert, whom he had met in Vienna. He was also employed by the composers George Gershwin and Jerome Kern as musical director of two Broadway plays.

Steiner signed his first Hollywood contract with the RKO studio at a moment when talkies were coming into vogue. Yet Steiner had to convince producers and directors that music enhanced the quality of a film. By 1932, he and Selznick had collaborated on over two dozen films.

Impressed by Steiner’s scores, rival studios expanded their music departments and hired composers such as Franz Waxman and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, both of whom had been hounded out of Nazi Germany.

In 1937, Steiner moved to the Warner Bros. studio, commanding a weekly salary of $1,500, his highest to date. Within nine years, he was earning $2,250, the equivalent of $34,000 today. As Smith points out, he would never have a better contract.

Steiner’s father, to whom he was close, left Vienna in 1938 and settled in Los Angeles, where he died in 1944.

On the eve of World War II, he composed the music for Confessions of a Nazi Spy, an anti-Nazi film. He continued to contribute scores to more such movies.

Jack Warner, the president of Warner Bros., was pleased with his score for Gone with the Wind, which premiered in Atlanta. “You have done a great job for a great picture,” he wrote. Smith agrees with Warner’s assessment, saying his score imparted “both intimacy and the sweep of grand opera.” He adds that this blockbuster film brought him enhanced prestige in Hollywood and at Warner Bros.

Another one of Steiner’s defining scores, Casablanca, earned him high praise from its director, Michael Curtiz, who claimed it was his “best and most brilliantly conceived work.” In Smith’s opinion, Steiner reached the peak of his game in the mid-1940s, when his gift for creating “psychologically incisive music and indelible character themes was undiminished.”

But in his personal life, chaos reigned. He was a spendthrift who mismanaged his finances. His eyesight was failing and soon he would be legally blind. Fortunately, two cataract surgeries restored much of his vision. His beloved, rebellious and pampered son, Ronald, committed suicide, sending him into purgatory. His marriages floundered, his spouses feeling neglected by his workaholic habits.

During the mid-1950s, he endured a stretch of unemployment, but bounced back triumphantly with a hit song he wrote for A Summer Place. It was one of the best-selling scores in the history of recorded music. The royalties solved Steiner’s money problems once and for all.

Much to his regret, the last film he worked on was a low-budget horror comedy that he condemned as “an abortion.” He retired shortly afterward.

Steiner died in 1971 at the age of 83. A eulogist at his funeral said, “Do you think Maxie is dead? No. His music will live on like those men of Vienna whom he followed — Mozart, Beethoven, the Strausses, all of them.”

This eulogy was overdrawn, but Steiner left an indelible legacy, as Smith constantly reminds us in Music by Max Steiner.