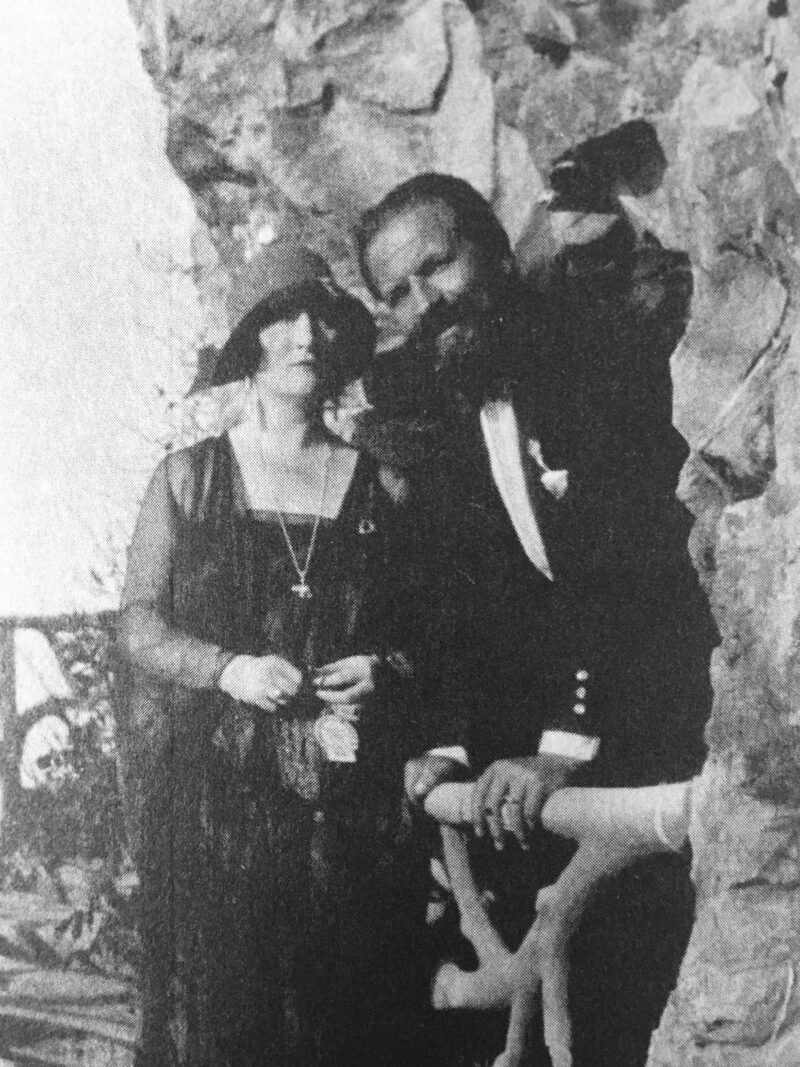

It was dubbed as a “Fascist Wedding in Rome” by the society page of The New York Times. The unlikely marriage between Attilio Teruzzi, an army officer and one of the rising stars of the Italian fascist movement, and Lilliana Weinman, an American Jewish opera singer, took place in June 1926.

Benito Mussolini, the supreme leader of Italy and the head of its fascist party, was Teruzzi’s best man.

The governor of Rome officiated at their civil ceremony, which was followed by a church wedding at the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels. Six hundred guests attended the glittering reception.

It didn’t seem to matter to Mussolini that Weinman, whose stage name was Lilliana Lorma, was Jewish. After all, Mussolini’s lover, Margherita Sarfatti, was Jewish, too. As far as he was concerned, Weinman was an American, period. Antisemitism would become a menacing factor in Italy only in the late 1930s. So for now, Weinman’s Jewishness was not an issue.

Three years later, after Teruzzi’s appointment as national commander of the Blackshirts, the paramilitary force that protected Mussolini’s regime, he renounced his marriage, claiming she had betrayed and dishonored by his bride. Since Italy had no divorce law, he sought an annulment, but Weinman stubbornly resisted.

Their tempestuous relationship, along with Teruzzi’s dazzling career and his affair with another woman of Jewish descent, form the backbone of Victoria de Grazia’s splendid work, The Perfect Fascist: A Story of Love, Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy, published by Harvard University Press.

Born in Milan in 1882, Teruzzi was an arresting figure. An affable socializer and horseman who played tennis and fenced, he was a dandy who could speak French and had a taste for gorgeous dress uniforms. Like many European military officers of that era, he groomed his facial hair meticulously, favoring a moustache, sideburns and a beard.

Having fought in a colonial war in Libya and in World War I, he joined the fascists in December 1920, before Mussolini’s ascent to power. Elected to parliament in 1924, Teruzzi was promoted to the powerful position of undersecretary of state of the Ministry of Interior in 1925. A year later, he served as governor of the Libyan province of Cyrenaica. In 1928, he was appointed commander of the 350,000-strong Blackshirts. On the eve of World War II, he was named the minister in charge of Italian colonies in Africa.

Mussolini valued Teruzzi, calling him “a soldier and fascist, valorous in the Great War and loyal in every moment of the fascist revolution.” In short, he was “a perfect fascist,” writes de Grazia, a professor of history at Columbia University.

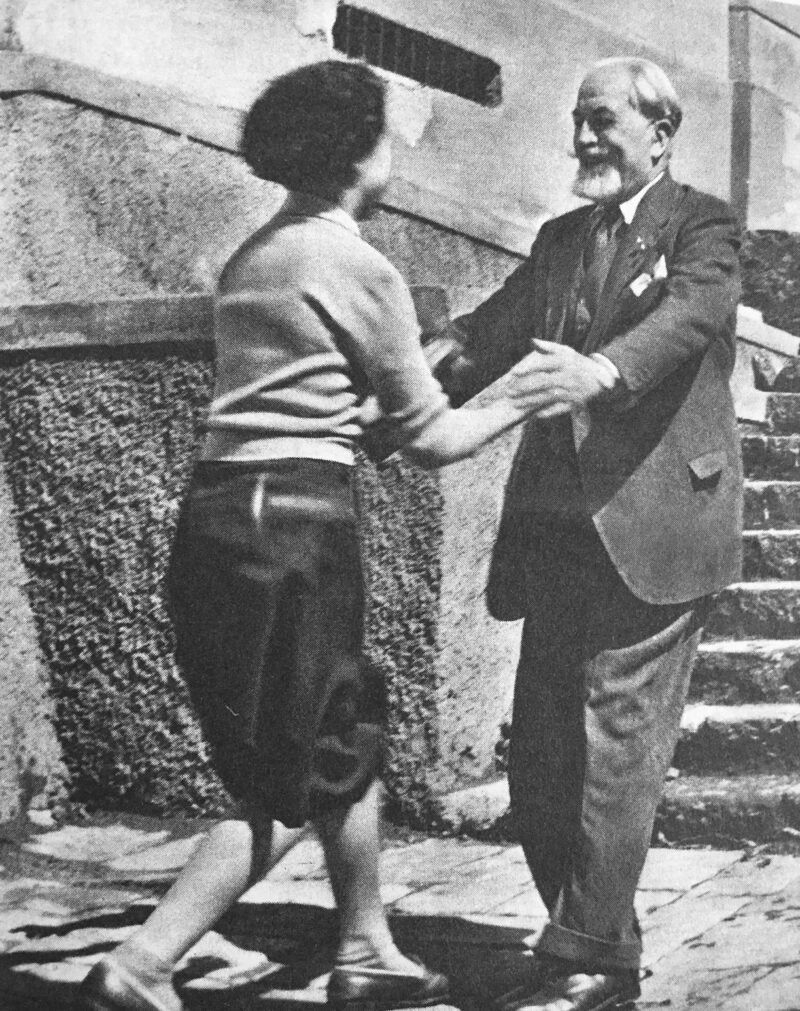

Teruzzi met Weinman in 1920 in Milan, where she was completing her operatic studies. But their courtship really began in 1925.

De Grazia has a high opinion of Weinman, whose wealthy parents, Isaac and Rose, hailed from the southern Polish city of Rzeszow. As she puts it, “Lilliana believed in her art, hard work, and the success arising from both. Unlike the Italian woman of aristo-bourgeois wealth, she had no family estates, no stash of ancestral porcelain and silver plate, baroque paintings, or antique furniture. She was the pure product of America’s grand experiment in meritocracy, entirely self-made, deservedly successful and thus a demonstrably superior person.”

De Grazia says that one of her mentors was Tullio Serafin, Arturo Toscanini’s successor at the La Scala opera house.

A secular Jew, Weinman did not have to convert to Christianity to marry Teruzzi. She received a special dispensation from the Catholic Church after promising to study catechism, baptize their children, and uphold her husband’s religious inclinations.

Interestingly enough, she was not his first Jewish girlfriend. While serving in Libya, he fell in love with a Jewish woman, the daughter of a merchant or cafe owner.

After the collapse of his marriage, Teruzzi met Yvette Maria Blank, supposedly a Coptic Christian who, in fact, was Jewish. He couldn’t marry Blank since he was legally married to Weinman, but they had a daughter, Celeste, who was born out of wedlock in 1938. As Italy’s alliance with Nazi Germany tightened and as Italy restricted the civil rights of Jews, Blank’s racial origins developed into a sensitive problem.

Once Weinman and Teruzzi parted ways, Weinman’s status as a Jew came into play. Teruzzi’s defenders made the case that he had been tricked into the marriage by a seductive and treacherous Jew. Weinman, however, did not believe her husband was anti semitic.

De Grazia takes a middle-of-the-road approach to this issue. After the Italian government passed its first antisemitic laws in 1938, he tried to help some Italian citizens of Jewish or partial Jewish descent. But in 1942, having come under increasing pressure to show his antisemitism, he decreed that Libyan Jews should be subjected to exactly the same restrictions as Jews in Italy.

The Italian fascist movement treated Jews as equal citizens for almost the first 20 years of its existence. But in the wake of Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy in May 1938, the Fascist Grand Council approved a package of antisemitic legislation, which was passed by the Council of Ministers and signed into law by the king on November 11, 1938, a day after the Kristallnacht pogroms in Germany. The Roman Catholic Church did not oppose these harsh limitations on Jewish rights.

Among the Jews affected by the race laws was Mussolini’s office manager, Jole Foa, who had been a loyal employee for 12 years, and Mussolini’s Jewish mistress, Margherita Sarfatti, who was forced into exile.

Weinman left Italy for good in 1938, returning to her home in New York City, where she joined the family business. She visited Italy after the war, but her romance with it had dissipated. She paid her visit visit in 1953.

She refused to grant Teruzzi an annulment on principle, claiming there had never been a divorce in her family. De Grazia doesn’t buy her rationale: “Lilliana saw no paradox at all in an American Jew fighting the Catholic Church to defend her right to preserve her marriage with a cad and a fascist, a declared antisemite, and an enemy of her country.”

Teruzzi’s career flourished during the first years of the war. He attained the rank of general, and in 1940, following Germany’s conquest of France, Hitler granted him a meeting. While in Berlin, he conducted talks with Reinhard Heydrich, one of the highest-ranking SS officials.

The anti-fascist movement declared Teruzzi guilty of war crimes after Allied troops liberated Rome in June 1944. Captured in northern Italy by partisans, he was placed on trial. He received a 30-year prison sentence and his properties were confiscated.

He spent the next five years in jail on the island of Procida, and was released in March 1950. Within a few days of being set free, he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. He died in April of that year.

Weinman, known as the Countess Attilio Teruzzi, passed away in 1987, the widow of the perfect fascist.