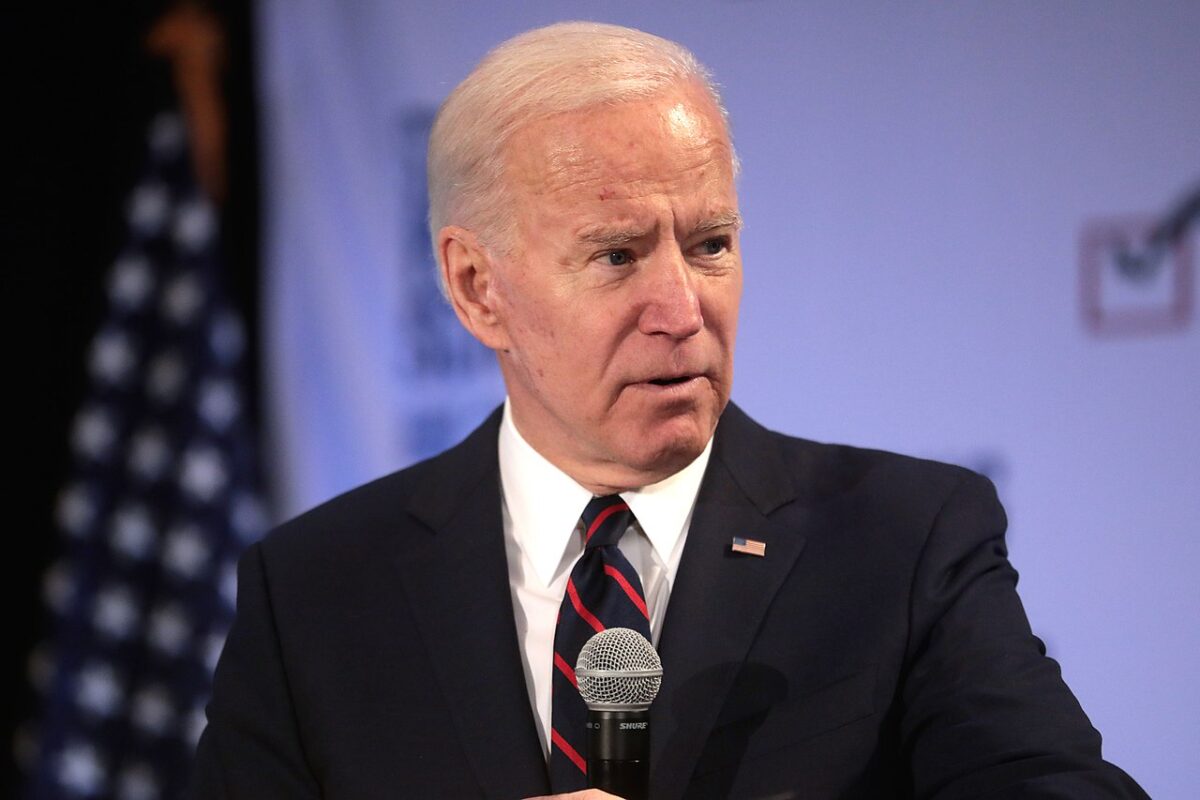

After nearly six months in office, President Joe Biden is tweaking rather than altering U.S. policy in the Middle East vis-a-vis Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iraq and Syria.

Apart from concerted efforts by the United States to normalize relations with the Palestinians and return to the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, Biden is more or less adhering to the status quo ante established by his predecessor, Donald Trump.

Trump, a disrupter of conventional political norms, upended U.S. policies with respect to Israel.

As per his election campaign promise, he recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, moved the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, and folded the American consulate in East Jerusalem into the embassy.

He recognized Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights. And he was instrumental in laying the groundwork for Israel’s breakthrough normalization agreements with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco.

As widely expected, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said the United States will honor Trump’s reversals on Jerusalem, but will reopen the consulate in eastern Jerusalem, which has dealt exclusively with Palestinian issues since the Six Day War.

And as Blinken said earlier this month, he has no intention of changing Washington’s position on Israel’s occupation of the Golan, which was captured by Israel in the 1967 war and effectively annexed by the Israeli government in 1981.

“As a practical matter, Israel has control of the Golan Heights, irrespective of its legal status, and that will have to remain unless and until things get to a point where Syria and everything operating from Syria no longer poses a threat to Israel, and we are not anywhere near that,” he said, referring implicitly to the current civil war in Syria.

Two months ago, Blinken not only voiced support for the Abraham accords, which Israel and four Arab states signed in 2020, but expressed a desire to expand them. “I expect Israel’s group of friends to grow even wider in the year ahead,” he said without spelling out the details.

In explicitly endorsing these historic agreements, the Biden administration joined Israel in approving the sale of F-35 stealth fighter jets to the United Arab Emirates.

While expressing support of the two-state solution, Blinken urged Israel to ensure that, in the meantime, the Palestinians in the West Bank enjoy “equal measures of freedom, security, prosperity and democracy.”

Blinken issued this comment shortly before the United States broke with Trump’s policies and restored humanitarian aid to the Palestinian Authority and the United Nations agency that assists Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

And in another break with the Trump administration, Blinken criticized Israel’s settlement policy in the West Bank. He said that Israel should refrain from taking “unilateral steps that exacerbate tensions and that undercut efforts to advance a negotiated two-state solution.”

Blinken referred to the West Bank as an “occupied” territory, a designation from which Trump notably departed. Blinken’s predecessor, Mike Pompeo, did not consider Israeli settlement construction in the West Bank as illegal under international law.

While Trump withdrew from the Human Rights Council, a United Nations body biased against Israel, Biden has returned to it as an observer with the caveat that its “disproportionate focus” on Israel is unwarranted and must end.

During the recent cross-border war in and around the Gaza Strip, Biden was supportive of Israel while seeking a ceasefire.

As the fighting raged, Biden repeatedly spoke to the then Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. This was a sharp departure from previous practice. After his inauguration in January, Biden waited about a month before phoning Netanyahu, causing concern in Israel that Biden was snubbing him. In a statement to the press following their one-hour conversation, Biden affirmed his “steadfast commitment to Israel’s security and conveyed his intention to strengthen all aspects of the U.S.-Israeli partnership, including our strong defence cooperation.”

Last week, U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin confirmed that the Pentagon will replenish the Iron Dome, Israel’s missile defence system, which intercepted 90 percent of the rockets fired by Hamas at Israeli cities.

Prior to his announcement, U.S. Senator Lindsay Graham disclosed that Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz was planning to submit a $1 billion replenishment request. “Iron Dome performed incredibly well,” he said. “I would imagine that the (Biden) administration will say yes to this request and it will sail through Congress.”

As well, the Biden administration has agreed to move forward with the sale of precision-guided missiles to Israel, a deal that is worth $735 million.

While campaigning for his party’s presidential nomination, Biden vowed that Egypt, a key Arab ally of the United States, would receive “no more bank checks” due to its dismal human rights policy.

Following a telephone call with his Egyptian counterpart, Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, Blinken said that human rights would figure significantly in the Biden administration’s relationship with Egypt.

Before they spoke, the United States approved the sale of almost $200 million worth of naval surface-to-surface missiles to Egypt. The U.S. State Department justified it on the grounds of bolstering the security of “an important strategic partner in the Middle East.”

The Biden administration indicated it would “recalibrate our relationship with Saudi Arabia” after he denounced it as a “pariah state” during his run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.

Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki, explained that his communications with Saudi Arabia will be conducted through King Salman rather than through his son and heir-designate, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who was accused of masterminding the assassination of Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 in Turkey.

There have been two major changes in U.S. policy since then. Biden has ended U.S. support for Saudi Arabia’s role in the war against the Houthis in Yemen. And in the interest of continuing the uninterrupted flow of humanitarian aid to Yemen, he has scrapped the Trump administration’s classification of the Houthi rebels as a terrorist group.

More importantly, Biden will maintain strategic ties with Saudi Arabia so as to preserve the American counter-terrorism campaign and contain Iran.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s decision to buy the S-400 missile defence system from Russia has frayed Turkey’s relations with the United States. As a result, the Trump administration cancelled the delivery of F-35 aircraft to Turkey. Despite this disagreement, the Biden administration is trying to keep its bilateral relations with Turkey on an even keel so that its military bases on Turkish soil will remain in place.

In Iraq, a country invaded by the United States in 2003, the Biden administration has opted for an advisory role. At present, there are 2,500 U.S. troops in Iraq, charged with training the Iraqi army and keeping the remnants of Islamic State at a bay.

But as General Kenneth McKenzie — the commander of American forces in the Middle East — said recently, “I don’t see us withdrawing from Iraq in the future.”

Pro-Iranian militias have regularly launched rocket attacks against U.S. bases in Iraq, where Iran has increasingly gained influence. This past winter, the U.S. Air Force bombed a cluster of buildings in eastern Syria belonging to two Iranian-backed militias believed responsible for the bombardments.

These limited strikes were intended to put Iran on notice that its proxy war against the United States is fraught with danger, but it is debatable whether Tehran has been sufficiently intimidated. American military sites in Iraq remain vulnerable.

As for Syria, the United States is keeping it on the back burner for now. In their first foreign policy speeches, neither Biden nor Blinken even mentioned Syria. Nor has Biden named a permanent replacement for Joel Rayburn, the U.S. special envoy to Syria, who assumed his post after his predecessor, James Jefferey, retired.

Nevertheless, the United States maintains a modest military presence in northeastern Syria, backs Kurdish fighters fending off Islamic State fighters, and supports rebels still trying to unseat Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.