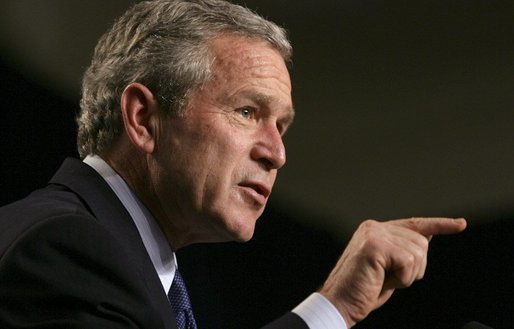

The architect of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was President George W. Bush’s deputy secretary of defence, Paul Wolfowitz. This is the considered opinion of Robert Draper, the author of To Start A War: How the Bush Administration Took America Into Iraq, published by Penguin Press.

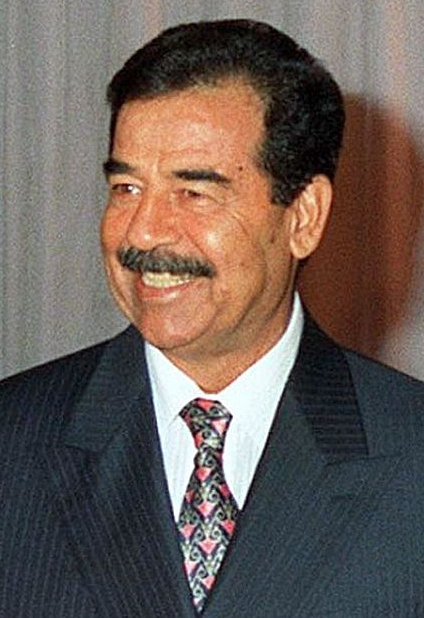

The decision to invade Iraq and depose its autocratic ruler, Saddam Hussein, and his Ba’athist regime was made by Bush, of course. But it was Wolfowitz, more than perhaps any other highly-placed and influential American figure, who had spent the previous decade calling for Saddam’s overthrow and “lending an otherwise beleaguered cause both intellectual brawn and moral ballast and, finally, a political path to realization.”

Wolfowitz, the son of a Polish Jewish mathematician whose family had been murdered during the Holocaust, was a mover and a shaker in Washington. He was the U.S. ambassador to Indonesia during part of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. And in George H. W. Bush’s administration, he served as an undersecretary for policy under Defence Secretary Dick Cheney, who admired his capacity for creative thinking.

Convinced that Saddam might have been involved in Al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, Wolfowitz argued that he represented the “head of the snake” in the network of global terrorism. It was a theory that was roundly rejected by, among others, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Counterterrorism Center, Cofer Black, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General High Shelton.

Wolfowitz also believed that Iraq’s nuclear, biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction had not been destroyed by United Nations arms inspectors after the 1991 Gulf War.

Animated by such convictions, Wolfowitz called for the ouster of Saddam and his repressive government. “We should invade southern Iraq, seize the oil fields, base ourselves in Basra and from there launch raids in Baghdad, and little by little we will bring the regime down,” he told Christopher Meyer, the British ambassador to the United States, in 1998 when he was dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Due to Saddam’s attempt to assassinate his father, George W. Bush was as hostile to Saddam as Wolfowitz. “Still, Bush’s disdain of Saddam fell well short of all-consuming,” writes Draper, a freelance American journalist, in this absorbing book. “Not once during the 2000 campaign did he advocate regime change in Iraq as his goal.”

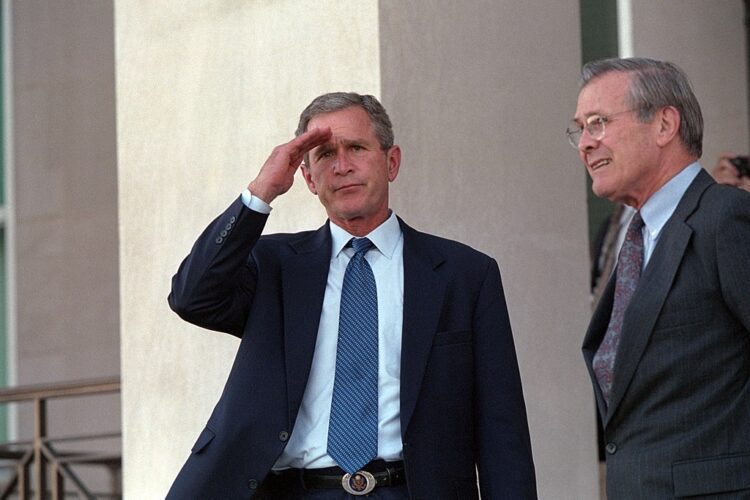

To Bush, Saddam was a problem to be managed and, whenever possible, ignored. But after 9/11, Bush instructed his national security advisor to ascertain if Saddam had been involved and asked Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz’s boss, for a military plan to deal with Iraq in case the need arose.

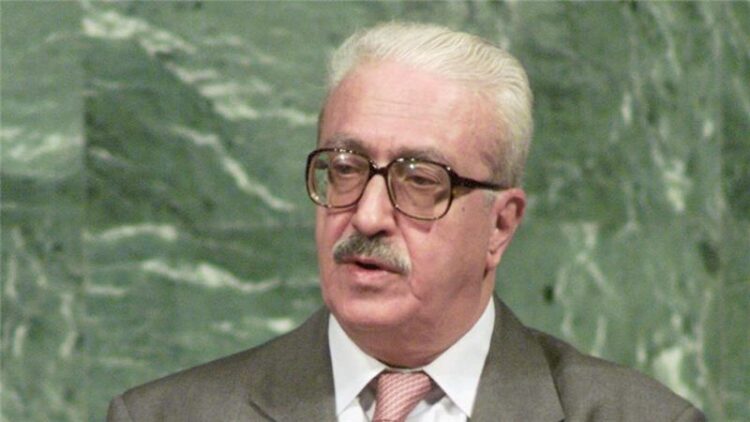

In the meantime, Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz let it be known that Iraq was not looking for trouble and sought a dialogue with the United States.

Toward the close of 2001, the commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, General Tommy Franks, presented Bush and his cabinet with a blueprint for invading Iraq. “What Franks laid out was not Wolfowitz’s modest scheme of establishing an enclave in southern Iraq, seizing Saddam’s oil fields, hammering Baghdad with air strikes, and then largely standing back while an indigenous opposition army swarmed the capital city and toppled the regime,” says Draper. Instead, it was a concept to unseat Saddam and unearth his weapons of mass destruction. “It constituted a U.S. commitment to war.”

Shortly afterward, Bush condemned Saddam. “Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and support terror,” said Bush, adding that his pursuit of weapons of mass destruction was intolerable. And in a reference to Iraq, North Korea and Iran, he said, “States like these, and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world.”

Bush’s denunciation of Iraq was hardly surprising.

Iraq had severed diplomatic relations with the United States in the wake of the Six Day War to show its displeasure with Washington’s support of Israel. The U.S. restored ties with Iraq in 1984 out of concern that its rival, Iran, might win the Iraq-Iran War.

In the winter of 1990, the first Bush administration dispatched an envoy to Baghdad to inform Saddam that the United States was interested in establishing cordial relations with Iraq.

Saddam remained suspicious that the United States would eventually turn against him.

It was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 galvanized Bush to form an anti-Iraqi coalition, which liberated Kuwait. Eight years later, the U.S. Congress passed the bipartisan Iraq Liberation Act to support efforts to remove Saddam’s regime and promote the emergence of a democratic government in Iraq.

Ahmad Chalibi, an Iraqi exile who hated Saddam, helped secure the passage of this bill. The scion of a prominent Shi’a family, he would settle for nothing less than his ouster and believed that the Arab-Israeli conflict could be resolved after he was unseated.

Despite his differences with the United States, Saddam ordered Iraq’s ambassador to the United Nations, Nizar Hamdoon, to reach out to the Central Intelligence Agency throughout the 1990s to lower tensions with Washington.

Hamdoon’s overtures were futile. Rumsfeld’s two deputies, Wolfowitz and Douglas Feith, believed that regime change in Iraq was unfinished business due to the U.S. decision in 1991 to leave Saddam in power. Rumsfeld himself had yet to decide what should be done.

The one issue that virtually everyone in the Bush administration could agree on was that Iraq had retained some of its weapons of mass destruction after the first Gulf War and could produce more if it so desired. According to Draper, this was a fallacy, based on information that was “badly outdated, almost completely circumstantial, and often fabricated.”

Saddam’s son-in-law, Hussein Kamel, told interrogators in Jordan after defecting in 1995 that Iraq’s stock of chemical weapons had been destroyed. The Central Intelligence Agency, however, had no physical evidence to substantiate this claim.

Nor could the head of the United Nations weapon inspection team, Hans Blix, confirm that Iraq had been stripped of its weapons of mass destruction.

Bush had no hard information as to how close Iraq was to developing a nuclear weapon, but he cast his doubts aside. “We cannot wait for the final proof — the smoking gun — that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud,” he said ominously.

Midway through his book, Draper examines a related issue: the absence of postwar planning after the U.S. occupation of Iraq. Wolfowitz claimed it was mostly unnecessary because Iraqis would greet their Western liberators joyously and Iraqi oil revenues would pay for Iraq’s postwar development. His assumption was largely unchallenged in the Bush White House.

Draper says that U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell was privately leery about the prospects of an American invasion. He was concerned that an occupying force would get bogged down and that Iran would be strengthened.

Three months before U.S. and allied troops stormed Iraq, Saddam informed his generals that its illicit weapons program had been discontinued and that its weapons of mass destruction had been obliterated by United Nations inspection teams.

Wolfowitz, meanwhile, laid out the objectives of the Bush administration — the liberation of Iraq from Saddam, the removal of its weapons of mass destruction, the dismantling of its terrorist infrastructure, the maintenance of its territorial integrity, and the rebuilding of Iraq into a free and democratic state.

Bush himself believed that Iraq’s political makeover would induce Israel and the Palestinians to reach a peace agreement.

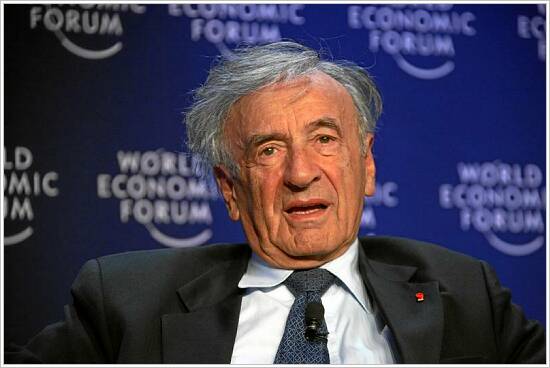

Less than a week before the launch of the invasion, Elie Wiesel, the novelist, Nobel Prize laureate and Holocaust survivor, visited the White House. Wiesel argued that World War II could have been averted if the United States and European countries had taken action against Nazi Germany in 1938. “In the name of morality, how can we not intervene,” he said of the imminent invasion. “Iraq is a terrorist state.”

As Bush would write, “The force of (Wiesel’s) conviction affected me deeply. Here was a man who had devoted his life to peace urging me to intervene in Iraq.”

Several days before the invasion, Bush denigrated Blix’s inspection efforts as a failure and claimed that his intelligence data “leaves no doubt that the Iraqi regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised.”

Less than a month after the entry of American and allied troops into Iraq, Bush stood on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln and prematurely declared that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.”

Says Draper, “The slogan accurately reflected the Bush administration’s wishful thinking and grandiose sense that history had already been made.”

Wolfowitz was surprised by the insurgency that erupted in Iraq following the invasion. Pentagon orders to de-Ba’athify the government and disband the Iraqi army had fostered resentments that fuelled the guerrilla war, which would be accompanied by a bloody Sunni-Shi’a sectarian struggle.

Bush thought that Saddam’s capture at the end of 2003 would defuse the insurgency, but it would only grow worse in the next few years. As for Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, they were never found by U.S. inspection teams.

As Draper suggests in his wide-ranging and expressive book, the underlying rationale for invading Iraq had proven to be devoid of substance.