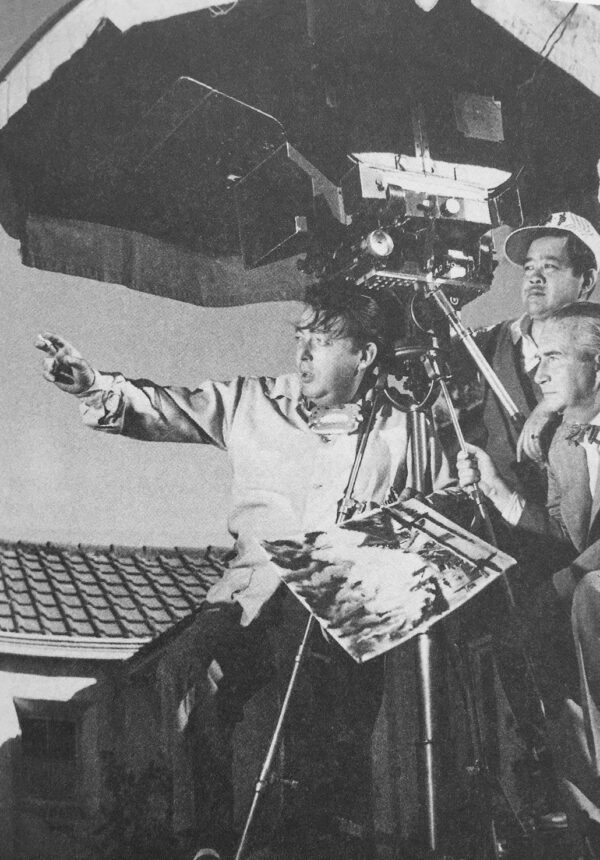

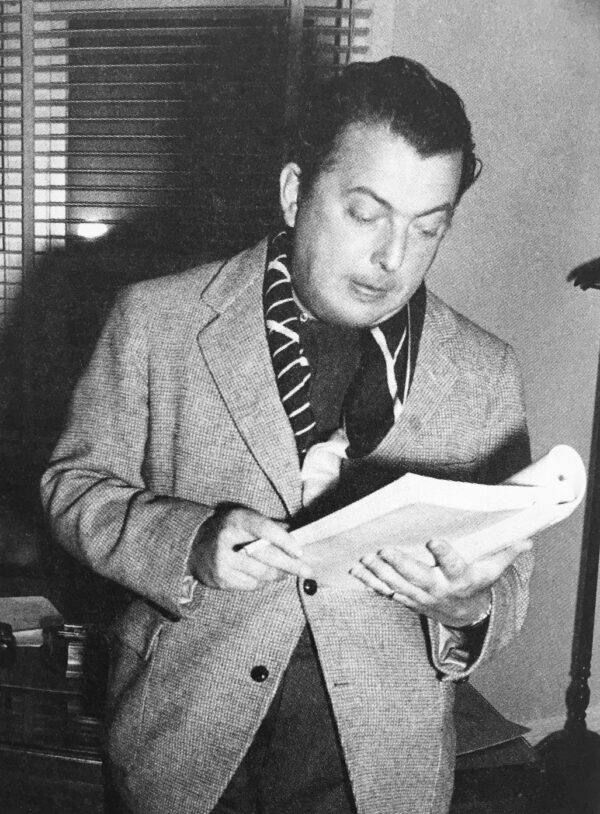

Lewis Milestone was a major figure in the Hollywood film industry during its golden era from the 1920s to the 1950s. One of its most imaginative and prolific directors, he churned out 38 films over a 37-year period from 1925 to 1962, amassing 28 Academy Award nominations and winning three Oscars.

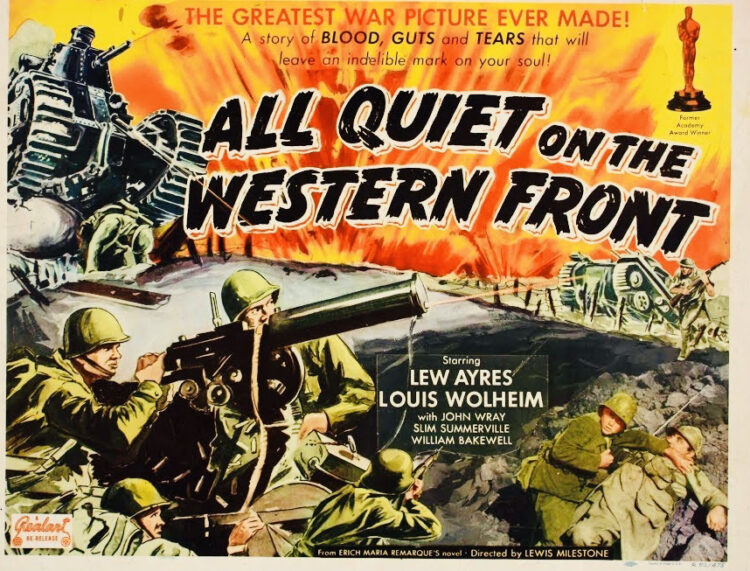

Several of his movies are recognized as classics — All Quiet On The Western Front (1930), The Front Page (1931), Of Mice And Men (1939) and Halls Of Montezuma (1951). Affectionately known as Millie, he directed a galaxy of stars ranging from Emil Jannings, Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich to Ginger Rogers, Errol Flynn and Gregory Peck.

Milestone brought to the screen the works of important writers: Erich Maria Remarque, Somerset Maugham, John Steinbeck and Lillian Hellman, among others. And he incorporated the scores of a procession of composers — Aaron Copland, Richard Rogers, Alfred Newman, Cole Porter, Nelson Riddle and Franz Waxman — into his pictures

Extremely versatile, he made the wrenching transition from the silent era to talkies with aplomb and worked successfully in a variety of genres. He directed musicals (Hallelujah, I’m A Bum, 1933), comedies (Ocean’s 11, 1960), war dramas (The General Died at Dawn, 1936) and costume dramas (Mutiny On The Bounty, 1962). And he turned out one film noir (The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, 1946).

Politically progressive, he used film whenever possible as a medium to convey messages of social relevance. His philosophy got him into trouble during the frenzied McCarthyist witch hunts of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Harlow Robinson’s comprehensive and highly readable biography, Lewis Milestone: Life and Films (University Press of Kentucky), covers his trajectory from birth in Russia in 1895 to death in the United States in 1980.

Milestone, whose real name was Lieb or Lev Milshtein, was born in the cosmopolitan port of Odessa, the son of a businessman. When he was five, his parents moved the family to Kishinev, the capital of the Russian czarist province of Bessarabia, which became part of Romania and is called Moldova today.

As a boy in Kishinev, Milestone battled pervasive antisemitism. One of his earliest memories was of witnessing the 1903 pogrom, which had an enormous impact on his development as a person and a movie director. “It helps explain why he was drawn to make films that deal with the persecution or exploitation of the less privileged by those in economic or political power,” writes Robinson, a professor emeritus of history and screen and media studies at Northeastern University and, since 2010, an Academy Film Scholar at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

He and two friends left Kishinev in 1913, bound for America. They spent their first night in New York City camped out in Central Park. For the next two years, he eked out a living as a manual laborer. In a raincoat factory, he got enmeshed in a labor-management dispute. Throughout his film career, as Robinson notes, he defended the rights of workers and unions.

In 1915, he gravitated into the world of photography, working as a technician in a darkroom, as an itinerant salesman and as a theatrical photographer. He enlisted in the U.S. army in 1917, joining the Signal Corps in the aerial photography division. Discharged from the army in 1919, he went west, having learned there was money to be made in the new and burgeoning movie industry in the Los Angeles suburb of Hollywood. By then, he had gained practical training in photography, editing and filmmaking.

Movies were a magnet for new immigrants like himself. The major studios had been founded by Jews from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

Milestone toiled in low-level positions before landing a job as an assistant film editor. Hired by the director William Seiter as his assistant, Milestone soon moved to Warner Bros., where he assisted Seiter on several films.

“For Milestone, editing was the key to filmmaking,” says Robinson. As Milestone himself would observe, “The cutting room was an excellent place to learn the rudiments of direction. My background there gave me a firm grasp on the mechanics of picture making.”

By 1925, he was ready to direct. His first film, Seven Sinners, was a comedy, like most of his silent features. He and a newcomer, Darryl Zanuck, co-wrote the script. Together they would write 19 scripts for Warner Bros. Zanuck would go on to be Warner Bros.’ head of production.

Due to being outspoken and authoritarian, Milestone earned a reputation as a cantankerous person who did not always try to ingratiate himself with producers or studio bosses.

Despite his image as a troublemaker, Milestone had a knack for meeting people who could advance his career. One such individual was the young oil tycoon Howard Hughes, who was drawn to movies. Hughes signed Milestone to a three-picture contract that proved mutually lucrative. The Arabian Knights, The Racket and The Front Page were all nominated for Oscars.

Milestone’s first talkie, New York Nights, was released in 1929. It was not a hit, but by then he had become an “insider, one of the founding fathers of the movie business.”

All Quiet On The Western Front, the first major war movie dubbed with sound, is described by Robinson as “a technical landmark in Hollywood history” and “a global box-office smash.” Premiered in Germany in 1930, it was denounced by the Nazi Party as a “Judenfilm.” But it picked up two Academy Awards and established Milestone as a celebrity.

The Front Page was its polar opposite, a frothy satire which underscored his versatility and further solidified his image as a leading director.

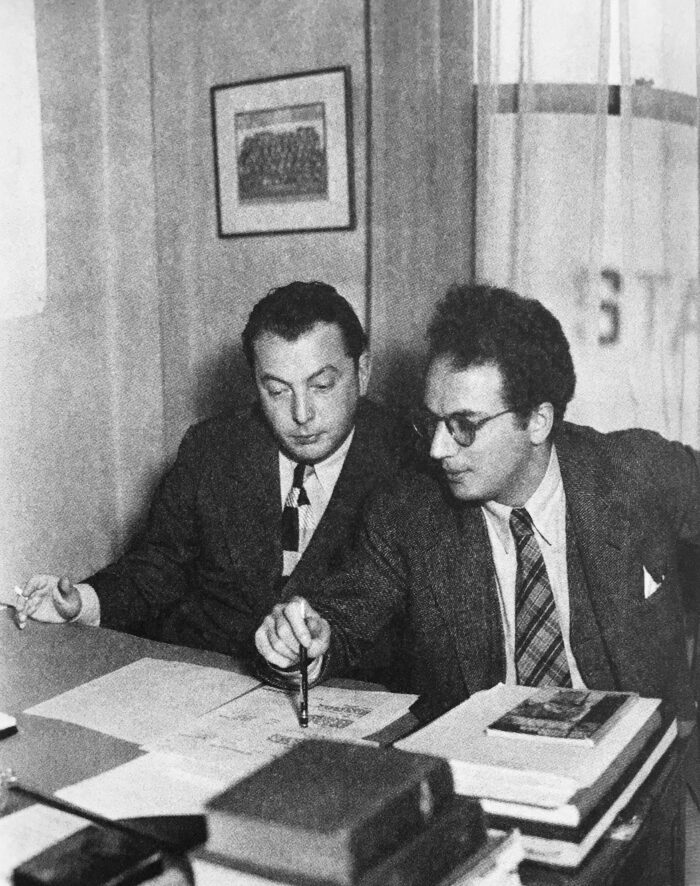

A judge of good writing, Milestone selected the playwright Clifford Odets to produce the script for The General Died At Dawn, which some had dismissed as pulp. Milestone also collaborated with John Steinbeck on Of Mice and Men and The Red Pony. According to Robinson, their relationship was exceedingly harmonious, both believing that literature and film should not only entertain but educate.

Of Mice And Men faced stiff competition for best picture of the year of 1939. The superlative contenders were Gone With The Wind, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, Ninotchka, The Wizard Of Oz and Stagecoach. Of Mice and Men received four Oscar nominations, but did not win in any category.

Still, it marked “an important turning point” in Milestone’s career, says Robinson. “After several years of drifting and unfinished projects, he had reestablished himself among Hollywood’s artistic leaders.” It also gave him financial security and renewed bargaining power for future projects.

From 1942 to 1962, he directed nine war films. “As a committed progressive and pacifist, with a strong personal interest in what was happening under Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism, he found renewed purpose in creating films dealing with stories of resistance, bravery and teamwork,” he says. “Several of these films, it is true, veer into the realm of propaganda — but propaganda for a noble cause. Nearly fifty, Milestone was too old to enlist as a soldier but uniquely qualified to contribute to the Allied cause through his art.”

His first effort was Our Russian Front, a short pro-Soviet documentary about Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. Within the next couple of years, he directed The North Star, a pro-Soviet movie which garnered six Oscar nominations, and The Purple Heart, which tells the story of the mistreatment of eight American airmen captured by Japan. “Today The Purple Heart seems uncomfortably nationalistic, racist and one-dimensional in its portrayal of both the Japanese and Chinese people, but at the time of its release critics hailed it as powerful … It was a movie that suited the mood of the times.”

One of his next pictures, The Strange Love Of Martha Ivers, dealt with themes such as crime, corruption, greed and revenge and starred Barbara Stanwyck and the newcomer Kirk Douglas. When Milestone started shooting it in the autumn of 1945, the term film noir, which had been reserved for low-budget B movies, was not yet in wide circulation. But it featured all the elements of this genre — strong narrative, somber nocturnal settings, glistening rain-drenched streets, swirls of fog, evocative sets and deep visual fields segmented by patterns of light and dark.

Another one of his postwar films, Arch of Triumph, was based on a bestselling novel by Erich Maria Remarque. Despite a big budget and a cast of glittering stars, it was a mismanaged and chaotic production and among the most damaging episodes of Milestone’s career.

In 1947, he received a subpoena from the House of Representatives’ Committee of Un-American Activities inviting him and 43 of his colleagues from the film industry to appear at a hearing in Washington. Milestone and 18 others, including the directors Edward Dmytryk and Robert Rossen and the writers Dalton Trumbo and Ring Lardner Jr., rejected the invitation, prompting The Hollywood Reporter to label them as “unfriendly.”

Robinson speculates that Milestone, a lifelong Democrat and an admirer of Franklin D. Roosevelt, was singled out for questioning because he had been born in Russia, had formed friendships with Soviet filmmakers, had directed The North Star, and had belonged to the Anti-Nazi League, which was later regarded as a Communist front organization.

For the next decade, Milestone remained under suspicion, was regularly visited by FBI agents and was tormented by conservative newspapers and magazines, which demonized him as a Communist. Like many others in the same position, he was hounded out of the United States. “It was pretty silly, but it drove me out of the business,” he said years later.

He and his high society wife, Kendall Lee, whose ancestors included Robert E. Lee, the commander of Confederate forces during the U.S. Civil War, moved to Paris. Thanks to Zanuck, who had become one of the most powerful players in Hollywood, Milestone was saved from oblivion. Zanuck asked him to direct a blockbuster film about the war in the Pacific, Halls Of Montezuma, as well as three other films of lesser importance, Kangaroo, Les Miserables and Melba.

Convinced by his financial advisor to cut short his sojourn in Europe, he and his wife returned to the United States in the mid-1950s. Milestone started working in television, a medium he did not view with either respect or interest. Fortunately for him, he was offered Pork Chop Hill, his seventh war film. It revived his flagging career and marked his successful return to Hollywood. “He was back in the game,” says Robinson.

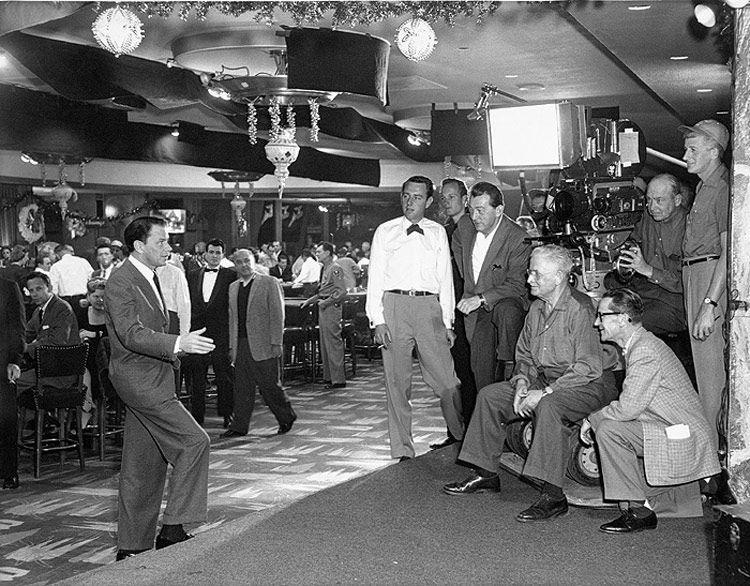

Milestone’s next movie, Ocean’s 11, a light comic caper starring Frank Sinatra and his friends in the so-called Rat Pack, also added lustre to his resume.

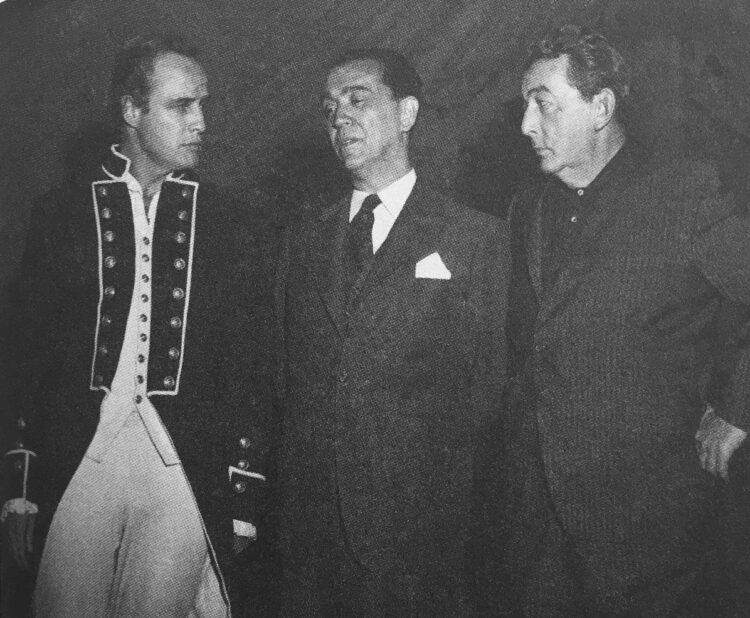

Robinson calls Mutiny On The Bounty perhaps his most complicated and physically demanding job and a film that brought him little pleasure. Ironically, it received more Academy Award nominations, a total of seven, than any of his previous films.

When it opened in theatres in 1963, he already had been fired from a new project, the first and only time he had been replaced during production. PT 109, based on President John F. Kennedy’s wartime service in the navy, was a disaster for Milestone because he and studio chief Jack Warner were constantly at odds, sparring over the script and the pace of production. PT 109 bombed at the box office.

As Milestone’s health declined, he tried to develop various projects, but none bore fruit. His wife died in 1978, and he outlived her by two years.

In summing up, Robinson theorizes that Milestone failed to achieve the same level of success as some of his more “diplomatic” contemporaries, like John Ford, Frank Capra, George Cukor or William Wyler, for a number of reasons. He was considered difficult. And at some crucial moments, he made questionable decisions about which projects to accept.

Yet he remained productive for almost four decades, and his best films are landmarks in the Hollywood pantheon of greatness.