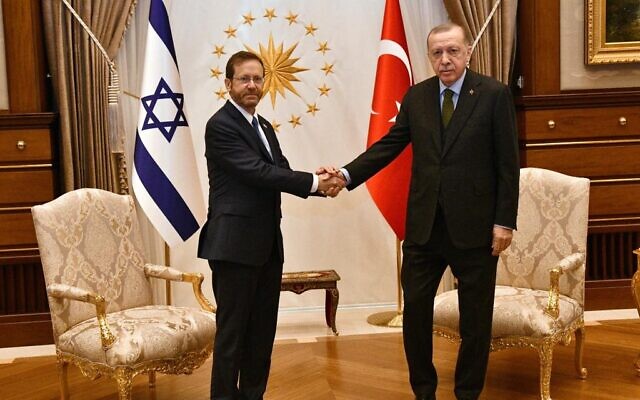

Israeli President Isaac Herzog spent a day in Turkey on March 9 hoping to reboot bilateral relations with Turkey after years of rollercoaster acrimony.

His host, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, struck an upbeat note, saying he believed that Herzog’s whirlwind visit would be “a turning point” in Turkey’s often contentious ties with Israel. “Strengthening relations with the State of Israel has great value for our country,” said Erdogan, an Islamist and a perennial critic of Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians.

Echoing his comments, Herzog declared, “Relations between Israel and Turkey are important to Israel, important to Turkey, and important to the entire region.”

Cognizant of Erdogan’s mercurial attitude to Israel, Herzog said, “The relationship with Turkey has had its ups and downs in recent years. We will not agree on everything, but we will try to restart relations. Hopefully, following my visit, a process of in-depth and serious dialogue with Turkey will begin at various levels, and we will eventually see progress and positive relations and results.”

Claiming he was “under no illusions” regarding the attainability of this objective, Herzog said he hoped he had laid the groundwork for a new and improved era in Israeli-Turkish relations.

This was certainly a pivotal moment in Israel’s relations with Turkey, the first Muslim country to recognize Israel. It was probably on a pair with Erdogan’s first and only visit to Israel in May 2005, just months before Israel withdrew unilaterally from the Gaza Strip.

Two years after Erdogan set foot in Israel, the then. Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, paid a visit to Turkey. And in the same year, the then Israeli president, Shimon Peres, addressed Turkey’s parliament.

These were the golden years when Israel’s strategic partnership with Turkey reached its peak.

Herzog’s visit may well have been on the same plane of importance. It unfolded in two cities. In Ankara, he met Erdogan. And in Istanbul, he paid his respects to the Jewish community at Neve Shalom synagogue, which has been attacked by terrorists three times since 1986.

Prior to leaving Ankara, Herzog announced that Turkey’s foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, would visit Israel in April to discuss ways of establishing a special mechanism to prevent future crises from spinning out of control.

Another topic on Cavusoglu’s agenda will likely be the full restoration of Turkey’s relations with Israel. Turkey recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv in 2018, less than two years after he had returned to Israel after a six-year absence. During this fraught period, the Turkish government ordered Israel’s ambassador out of Turkey.

Israel forged close political and military ties with Turkey in the mid-1990s, following the launch of the Oslo peace process and the hopes it inspired for reconciliation between Israel and the Palestinians.

In the wake of the first Gaza war in 2008-2009, however, Erdogan bitterly condemned Israel, branding it as a “terrorist state.” And in a juvenile spectacle at the Davos economic forum in Switzerland, he denounced Israel in the presence of Peres, who was clearly embarrassed and angered by his rant.

There was a further deterioration in Israel’s relations with Turkey in 2010 after Israeli naval commandos boarded a Turkish vessel, the Mavi Marmara, and killed nine Turks and one American of Turkish descent. The Mavi Marmara was the lead ship in a flotilla of boats attempting to break Israel’s siege of Gaza, which was seized by Hamas, a Turkish ally, in a bloody takeover three years earlier.

Israel and Turkey finally resolved their quarrel in 2016, following Israel’s decision to compensate the families of Turks who had been fatally shot aboard that ill-fated ship.

But in the spring of 2018, angered by Israel’s strong armed response to fierce Palestinian rioting along its border with Gaza, Erdogan went ballistic again. In a rage, he withdrew Turkey’s ambassador in Israel and kicked out Israel’s envoy, thereby returning to the status quo ante.

After these disruptions, Erdogan ratcheted up his verbal assaults on Israel, prompting the then Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, to respond in kind. These unpleasant incidents weighed heavily on Israel’s political relations with Turkey, but had no effect on its swelling level of trade and commerce with Turkey.

Starting last year, Erdogan and his advisors, worried by Turkey’s growing isolation in the region and the calamitous state of its inflation-ridden economy, decided they had nothing to gain and everything to lose by attacking Israel.

“We will exert efforts to move our bilateral relations to a very different place,” he said. “I can tell they (Israel) also have the same approach.”

Erdogan’s comments prompted his foreign policy advisor, Ibrahim Kalin, to initiate talks with Israel’s charge d’affaires in Ankara, Irit Lillian. This led to Erdogan’s invitation to Herzog to visit Turkey. Last month, Alon Ushpiz, the director-general of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, went to Turkey to prepare it.

Three days before Herzog boarded a plane bound for Turkey, a delegation of more than 100 Turkish businessmen, all members of the Turkish Exporters Assembly, arrived in Israel to meet their Israeli counterparts from the Federation of International Chambers of Commerce. It was the largest such delegation from Turkey to arrive in Israel in years.

Uriel Lynn, the president of the federation, hailed the event as “a turning point in our future relations both Turkey.”

The volume of Israeli-Turkish trade has grown from $4.9 billion in 2020 to $6.7 billion in 2021, the coronavirus pandemic notwithstanding.

This figure is expected to grow exponentially if, as expected, Israel and Turkey succeed in normalizing relations. Judging by Herzog’s visit to Turkey, there is more than a fair chance that this will happen in the near future.