During the early 1960s, when we were teens, my friend Henry Srebrnik and I popped into a midtown cafeteria in New York City and found ourselves in a bright, bustling and unfamiliar world of fairly high ceilings, dome lighting fixtures, marble floors and tables, and chrome and glass dispensers.

We had entered the inviting domain of Horn & Hardart, which had the distinction of being the first and finest American automat and the largest restaurant chain in the United States.

Long before McDonald’s and Burger King became synonymous with fast food, Horn & Hardart was dishing out fresh, tasty and incredibly cheap fare to legions of consumers.

Founded by Joe Horn of Philadelphia and Frank Hardart of New Orleans, it perfected the complicated art of mechanized food delivery from shiny vending machines. For less than one dollar, you could enjoy a decent meal with all the trimmings and wash it all down with a hot cup of coffee.

I don’t quite remember what I had for lunch, but if memory serves me correctly it may have been a plate of steaming macaroni and cheese, topped off with a generous slice of warm apple pie and a glass of cold milk.

I recalled this fond figment from my youth after watching Lisa Hurwitz’s nostalgic documentary, The Automat, which is currently playing in Canadian theaters.

Founded in the late 19th century, Horn & Hardart revolutionized the restaurant scene thanks to its state-of-the-art technology, comfortable interiors and affordable quality food, which ranged from Salisbury steak and baked beans to creamed spinach and an assortment of pies and puddings, all cooked and baked in a central kitchen and on the premises.

It attracted an eclectic clientele from stenographers and clerks to executives and out-of-town visitors like myself and Henry. And in an era when racial segregation was the norm, it broke the mould by welcoming African Americans.

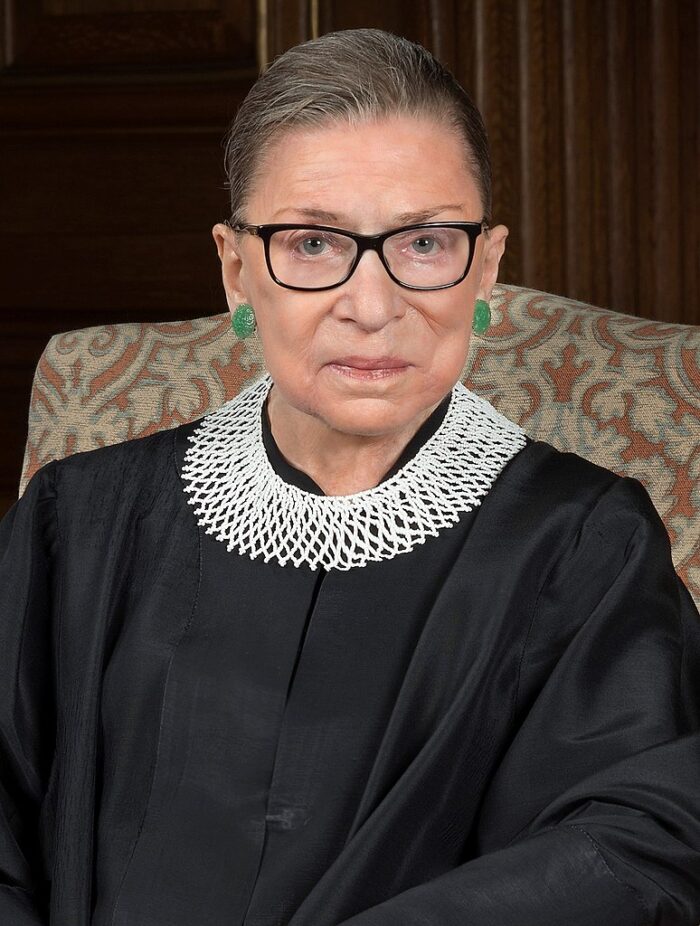

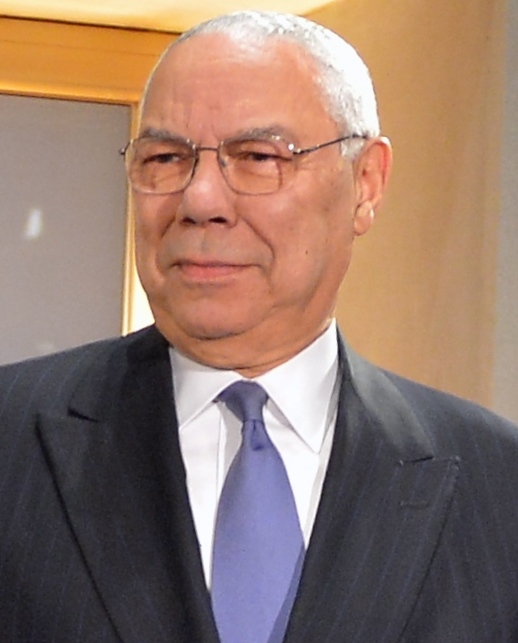

Hurwitz’s film unfolds through vintage photographs and old movie clips and on-camera interviews with New Yorkers, many of them Jews, who frequented Horn & Hardart. Some, such as Colin Powell, the former U.S. secretary of state, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the U.S. Supreme Court justice, achieved fame in their respective careers.

As Hurwitz correctly observes, Horn & Hardart was a prime tourist destination, on a par with the Statue of Liberty and maybe even the Empire State building. Mel Brooks, the comedian and film actor who grew up poor in Brooklyn, would eat there as an adolescent.

Unbelievably, back then, you could buy a plate of food for the grand sum of a handful of nickels. “You needed a lot of nickels, but not a lot of money,” says Brooks, fondly looking back to a time when inflation was low.

Howard Schultz, the chief executive officer of Starbucks, was so impressed by the Horn & Hardart concept that it inspired him to establish the nation-wide coffee chain.

Irving Berlin wrote a song about it after a visit.

Horn & Hardart thrived during the Depression, pleasing the palates of penny-pinching people. During World War II, it supplied U.S. troopships with hearty comfort food.

By Hurwitz’s estimation, it hit its peak of popularity in the 1950s, when it fed something like 800,000 people a day.

“It was a good place to eat,” says Ginsburg, who died last year. “The food was delicious. The price was right.”

Powell, who passed away in 2021 as well, liked its “beautiful diversity.” On a typical day, you could find diners there from every conceivable walk of life and racial origin, he says.

“Everything tasted delicious, even the napkins,” recalls the actor Elliott Gould.

Wilson Goode, the first black mayor of Philadelphia, remembers the meatloaf, his favorite signature dish. Most of all, though, he appreciated its openness. As he says, “It was a nice place where an African American could go and feel dignified.”

Horn & Hardart ran into resistance when it raised its price. It was also adversely affected by a population shift to the suburbs and the march of relentless inflation.

By the 1970s, its outlets had become somewhat dowdy, a refuge for vagrants and the homeless. Horn & Hardart attempted to burnish its declining image with the slogan, “It’s not fancy, but it’s good.” But the advertising campaign flopped, and the last Horn & Hardart restaurant in New York City closed in 1991, years after the chain’s failure in Philadelphia.

Brooks regrets its demise. “I wish someone could bring it back,” he laments.

Horn & Hardart is dead and buried, but Hurwitz lovingly brings it back to life in The Automat.