When Pearl (Polly) Adler disembarked at Ellis Island in 1913, she was among 13,588 “unaccompanied Jewish girls” from Eastern Europe who had landed in New York City in that year, according to the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society.

On the day she left her home in Yanow — a sleepy and changeless village of 3,000 Christians and Jews in the Russian Empire surrounded by dense forests, immense swamps and large estates — Adler’s mother packed an old potato sack with a few items she would need for the long voyage to the United States: clothes, four loaves of black bread, four salamis, cloves of garlic and apples.

Within a decade of arriving in America, or the goldenne medenne, as it was known in Yiddish, Adler had become a madam, the wealthy proprietress of Manhattan’s most renowned — or notorious — bordello. By then, she was raking in $60,000 a year, or $900,000 in today’s currency.

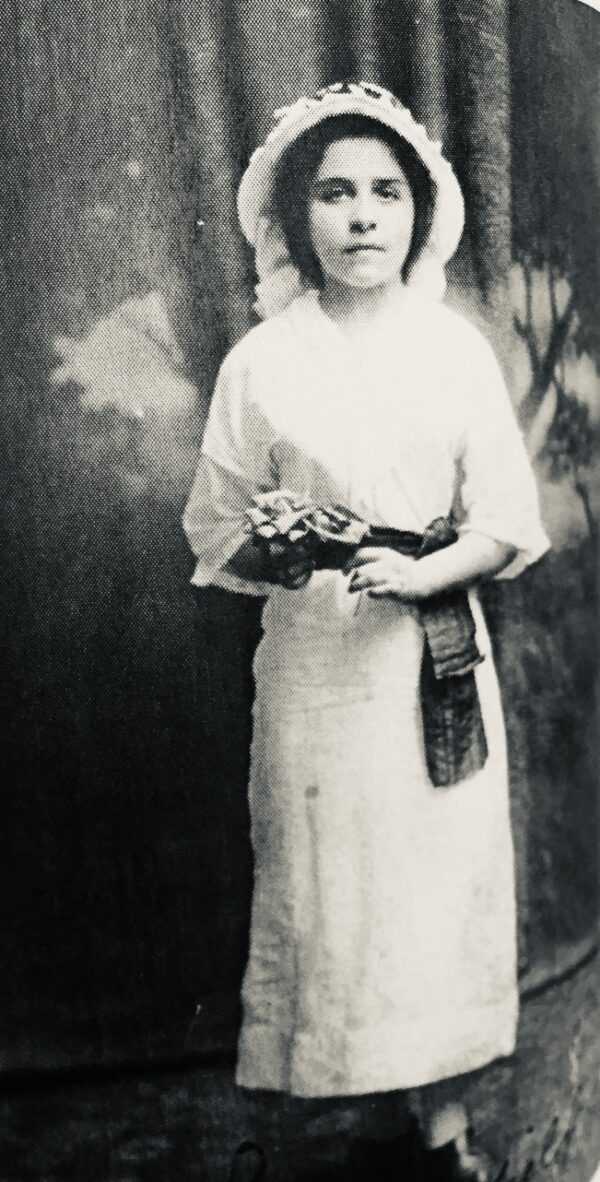

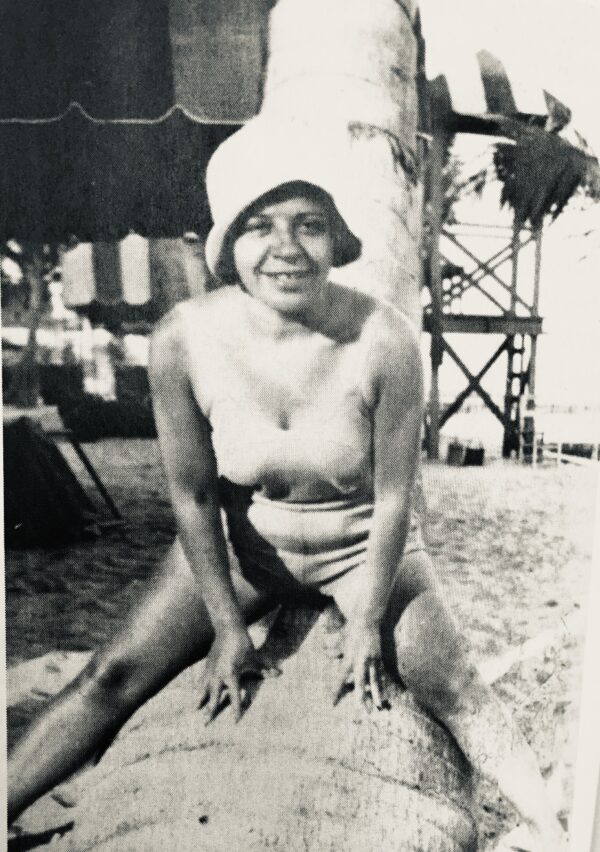

Barely five feet tall in high heels, flashing a sweet smile, she was a buoyant personality who spoke with Yiddish inflections, sprinkled with immigrant malapropisms and Broadway slang. She dressed primly in beautifully tailored clothes, though she had a weakness for mink coats and showy jewelry. Her hair was fashionably bobbed and her fingernails were tastefully manicured. Yet unlike the women of the night she employed, Adler did not wear heavy makeup.

“There were plenty of other madams in Manhattan, but none of them seemed to have the combination of charisma and brains that made Polly one of the ‘authentic Big Shots’ of the town, as one Broadway columnist dubbed her,” writes Debby Applegate in her superlative book, Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age, published by Doubleday.

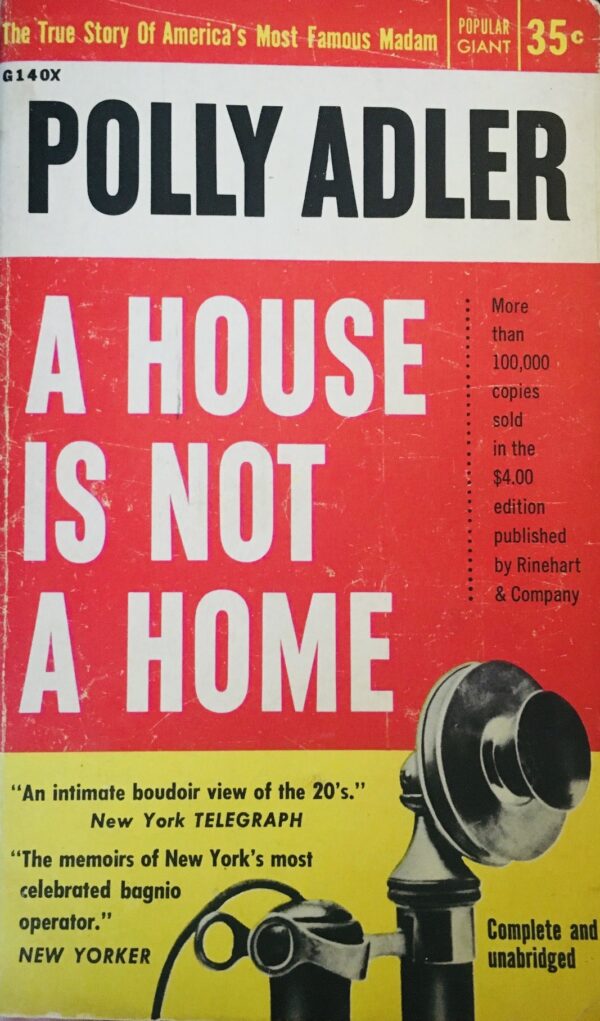

As Applegate judiciously notes, Adler was more modest about her success. “I was a creature of the times, of an era whose credo was: ‘Anything which is economically right is morally right,'” she wrote in her autobiography, A House Is Not A Home. “In fact, if I had all of history to choose from, I could hardly have picked a better age in which to be a madam.”

She opened her first “house of assignation” in a two-bedroom apartment across from Columbia University in 1920. She was only 20 years old, and New York City was on the cusp of a frenetic nine-year period of unprecedented prosperity.

Her clients, or johns, hailed from all walks of life — bootleggers, bookmakers, gangsters, gamblers, captains of industry, account executives, entertainers, politicians, conventioneers, salesmen and newspapermen, among others.

“Men sought out prostitutes for more than sexual relief, she soon realized,” writes Applegate. “They came to assuage loneliness or massage their egos, for relaxation, male camaraderie, or compensation for life’s disappointments, for the taste of power, or for the relief of letting down their public defences with someone who wouldn’t judge them.”

Being friendly and shrewd, Adler developed an aptitude for persuading customers to spend more money than they had intended, to tip well, and to become regular clients. “Men like flattery,” she said. “They’re vain and egotistical. Women can hold them if they just pretend.”

Delving into Adler’s childhood, Applegate presents her as an unusually clever and self-possessed, as her parents, Moshe and Gittel, knew. Their oldest child, she grew up in a seemingly timeless village in present-day Belarus, near Pinsk, where Jews comprised a little more than half its population of Belarusians, Poles and Russians.

By Yanow’s standards, the Adlers were well off. A tailor, Moshe lived with his family in a two-storey wooden house with a big yard, vegetable and flower gardens, an outhouse, a woodshed, and a barn to shelter a milk cow, a horse and chickens.

Like hundreds of thousand of Jews before them, antisemitism drove them out of Russia. Adler was the first to make the move. Her parents and brothers followed. Moshe, a man of the world, was acutely aware of the dangers that faced a young and vulnerable woman like his daughter. She would have to navigate a gauntlet of conniving steamship agents, roughneck sailors, slimy pickpockets, brutal police officers, and ruthless kidnappers who could sell a naive woman into prostitution in Argentina. Yet he was sufficiently confident she could manage and overcome these daunting hurdles.

Upon her arrival in New York, Adler decamped to Springfield, Massachusetts, the home of one of Moshe’s old friends from Yanow. A Hebrew teacher and a peddler of dry goods, he treated her kindly but indifferently. She enrolled in a local school, but was soon working in a low-wage job in a paper factory for 12 hours a day.

In 1915, she moved to Brownsville, a rundown neighborhood in New York City that resembled an East European shtetl. There she found an entry-level, back-breaking position in a corset factory that paid $5 per week.

As Applegate observes, her options were limited.

“A wedding was still the great goal … but marriage in Brownsville was no brass ring. For most women it meant an endless cycle of childbearing, hard-luck housekeeping, and scraping to make ends meet. Some lucky young women became stenographers, typists, department store clerks, or at the pinnacle of prestige, school teachers.”

Much to Adler’s misfortune, she was raped by the factory foreman. Finding herself pregnant, she had an abortion, which was illegal. Drifting aimlessly, she found a part-time job in another corset factory, but a general strike rendered her jobless.

Entering the world’s oldest profession, she turned her first “trick” at the age of 17, according to underworld gossip. “Suddenly, selling sex offered the answer to all her problems, a quick path to a glamorous life filled with cash, clothes and camaraderie,” Applegate writes.

In her memoirs, Adler was candid. “Economics, I suppose, drove me into it. I had no wish to marry a pickle factory foreman, or work for $3 a week in a Brooklyn corset factory. I was tantalized … by glimpses of an easier and more gracious life.”

A realist, she understood that her chances of success were far better in the role as a madam. As she put it, “I had to be a madam, I was never pretty enough to be a hustler.”

In Applegate’s recounting of Adler’s start in the business, she hooked up with a pimp named Nicholas Montana, and he set her up in a modest apartment in the Upper West Side. “I jumped at the offer,” she recalled. With his help, she soon had three girls servicing men from nearby speakeasies, dance halls and delicatessens. “It was in this informal, almost casual fashion that I began my career as a madam,” she wrote.

She regarded the sex business as “a temporary expedient, a means to an end,” but remained in it for more than four decades.

Her expenses were high. When she was not entertaining johns, she cultivated relationships with “go-betweens” — waiters, bar tenders, chauffeurs, taxi drivers, bus boys and elevator operators — who could guide men to her bordello for a small commission. The price of doing business was higher when the police were involved. To avoid arrest and shutdowns, she was forced to pay off police officers, bondsmen and lawyers. Nonetheless, she was repeatedly raided by police.

By Applegate’s reckoning, Adler was a consummate professional.

“It was an article of faith held by both urban reformers and the underworld that Jewish women made the best madams. This belief was backed by statistics. In the first decades of the twentieth century, when Jews were approximately 20 percent of New York’s population, they owned an estimated 50 percent of the city’s brothels. And for good reason.

“A successful madam needed to possess the efficiency of an office administrator, the discernment of a talent agent, and the social skills of a den mother. The shtetl tradition of a balaboosta — the cheerful, efficient wife who ran both the home and the family business while her husband studied Torah — developed in many Jewish women the rare combination of practical financial sense and homey hospitality required to run a successful house. This was certainly true of Polly. She was clever, quick on the uptake, (and) had a good head for math.”

It was incumbent on her to screen customers to ensure they were not policemen or, worse, madmen. To protect herself, she kept a “black book” of powerful men who frequented her bordello. It also fell on her to keep track of her clients’ preferences. And it was her responsibility to choose the right women. She recruited chorus girls, hostesses, entertainers and employees of boutiques, beauty parlors and drugstores. “They were all fair game as far as Polly was concerned,” says Applegate.

She took good care of her girls, providing them with under-the-counter diaphragms, regular medical examinations, and doctors in case of a pregnancy.

She offered her customers discreet, top-quality service. “She was known for running a deluxe hideaway where a man could have his fun any way he liked it, without fear of being blackmailed, rolled or swindled,” observes Applegate. “At Polly’s, you spent plenty, but you got what you paid for and left with your wallet and reputation intact.”

Adler’s reputation for discretion was universal. “She was the only madam in the whole city I could trust,” Applegate quotes the mobster Charles (Lucky) Luciano as saying.

Neither the stock market crash of 1929 nor World War II affected her business adversely. But in the mid-1930s, she pleaded guilty to a charge of keeping a house of ill repute. She was sentenced to 30 days in prison and fined $500.

As the 1940s wore on, she dreamed of ditching her vocation, plagued by the feeling that she was being bugged or followed by the police.

In 1944, she learned that the Red Army had driven German troops out of Yanow, but not before they had managed to murder its Jewish inhabitants.

A year later, she moved to Los Angeles for a fresh start. She enrolled in evening classes and acquired a high school degree in nine months. During this period, she wrote her memoirs with the assistance of a ghost writer. A House Is Not A Home, having been rejected by a string of publishers, was published in 1953 and received rave reviews, rocketed into best-seller territory, and sold an astounding two million copies.

The book was translated into Hebrew in Israel, where some of her relatives lived. But her visit to the Jewish state was unsatisfying. Family lore has it that her cousins were too embarrassed to even speak with her about it.

In 1961, she was diagnosed with lung cancer. Forty years of smoking had done her in. She died in the spring of 1962. Before she passed, she sold the film rights to A House Is Not A Home. The movie version, starring the Jewish actress Shelley Winters, was a flop, though the costume designer Edith Head was nominated for an Academy Award and the title song by Burt Bacharach became a top-100 hit.

By then, in Applegate’s view, Adler was “a certified American legend.” Hailed as a symbol of a decadent, long gone era, her career “coincided with New York’s flowering as the most vibrant … city in the world.”

In closing, Applegate argues that Adler was a “dealer in the illusions of intimate connection between strangers, of desires without limits or consequences, of spontaneous ecstasy on command, and whatever else the human id can dream up and pay for.” Adler’s mastery of this “mysterious art,” she believes, was the source of her significance.

Applegate, a seasoned historian with a Pulitzer Prize to her credit, has written a thorough account of an immigrant woman who might easily have been forgotten. Rich in historical, cultural and personal details and references, Madam is exceptionally well written, though far too often padded. Combining scholarship with journalism, it stands out as a paragon of biography.