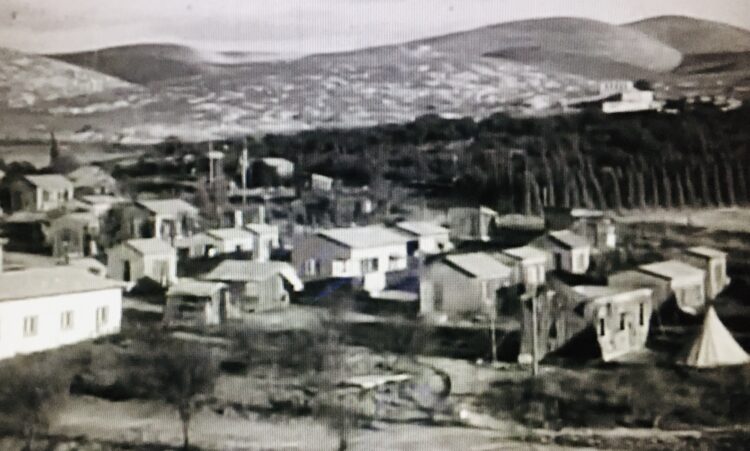

Left- wing Labor Zionists in Palestine and Israel attempted to build an egalitarian and socialist society within their web of cooperative settlements.

The children they raised in this cloistered milieu from the 1920s to the 1970s were expected to transmit their parents’ and grandparents’ hopes and dreams to future generations, but this would not be the case in many instances.

As times and values changed, the newest generation of kibbutzniks charted their own path into the shoals of modernity.

Ran Tal’s nostalgic documentary, Children of the Sun, which can be accessed on the website of the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation, traces this seismic ideological shift through the memories of middle-aged Israelis who grew up on kibbutzim and through the lens of file footage.

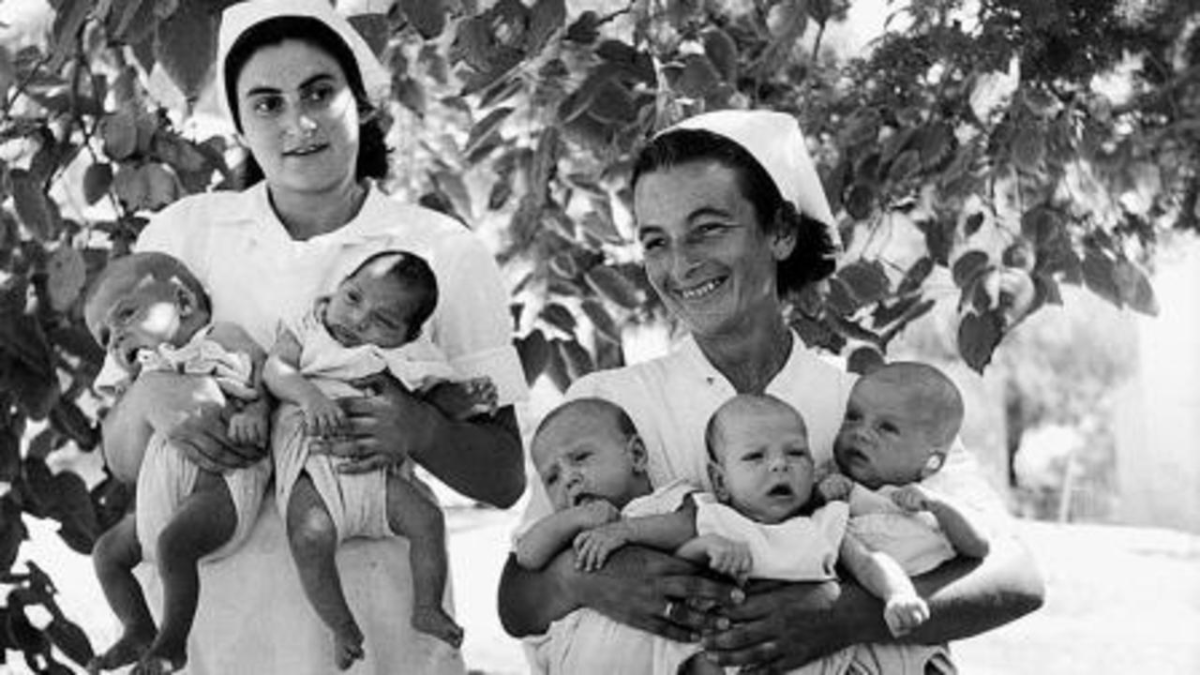

He focuses his gaze on children’s houses, which kept children and parents physically apart for much of the day and all of the night. Nurses, or nannies, attended to all their needs from the moment of their births until early adolescence.

As one of the kibbutzniks recalls, the typical nanny was usually a beloved and respected figure. “She was our whole world.”

When one of the nannies on a certain kibbutz died prematurely at the age of 40, a boy who had received her tender loving care cried the whole night in his bed.

On average, parents spent about one-and-a-half hours a day with their child or children, often enjoying their precious time together on the expansive and shady lawn of the kibbutz.

Some of the children really missed their mothers and fathers after they parted ways. As a woman remembers, “All I wanted was to sit next to my mother.”

Until they entered the sixth grade in school, boys and girls shared communal showers and ate meals in common. Not until the late 1960s or early 1970s were movies or television sets available to kibbutzniks. “We grew up ignorant of the outside world,” says a man.

Individualism was frowned upon and group identity was encouraged. Which is why a girl who received a sweater from her grandmother in the United States was eventually compelled to share it with her comrades.

Manual labor was considered uplifting, and the goal of a worthy kibbutznik was to be a good worker.

The children of kibbutzim enjoyed incredible freedom and believed they were part of something much greater than themselves. “Spiritually, we felt at the top of the world, as if we were members of an elite,” says a kibbutznik.

“We lived in a bubble,” observes another one. “We were the chosen ones.”

In their constricted view, city dwellers were rotten and lacked values. The death of a soldier from a kibbutz bonded kibbutzniks. May Day parades underscored their commitment to socialism and, at least for a while, their affinity with the Soviet Union.

The allure of consumerism in Israel dented their fealty to a simple spartan life and forced them to reconsider their commitment to children’s houses and a sense of togetherness.

Some outgrew their need for the extended kibbutz family. Others preferred to raise their children themselves. Still others were disillusioned with the lifestyle and left the kibbutz altogether with an ache in their hearts. To one woman, the act of leaving was akin to having to learn a new language.

Yet all of them agree that the kibbutz, in its prime, was a safe harbor, a culture on to itself, and a beautiful place.