Rashida Tlaib, the first Palestinian American to be elected to the U.S. Congress, introduced a unique and controversial resolution in the House of Representatives on May 16.

Its chance of passage is extremely slim, but its very appearance is unsettling and surely a sign of the times.

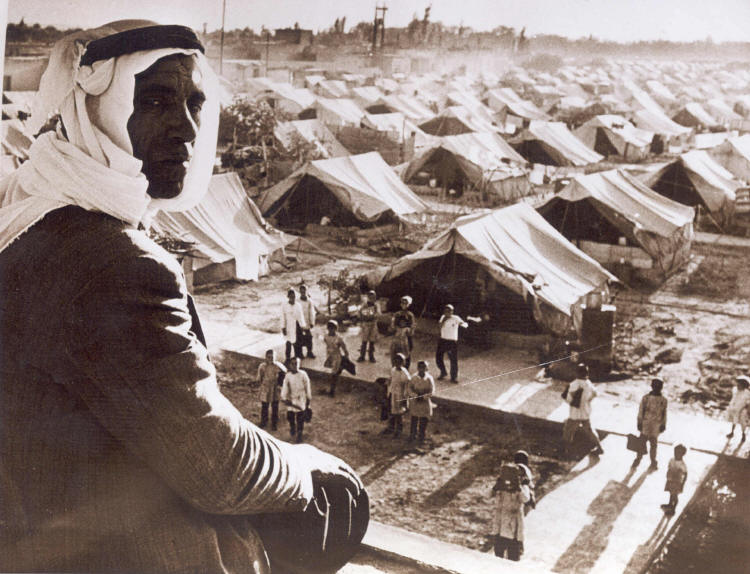

Tlaib’s resolution broadly calls on the United States to formally recognize the nakba, the displacement of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, and to support the implementation of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which enshrines the right of Palestinian refugees to return to what is now Israel.

She submitted it on the 74th anniversary of the nakba, an unmitigated disaster in Palestinian history. The voluntary and forced flight of Palestinians was traumatic in every conceivable respect and changed the demographic balance in Palestine and later in Israel. Understandably, the nakba is deeply seared into the consciousness of Palestinians wherever they may live today.

The resolution was co-sponsored by six members of the so-called progressive wing of the Democratic Party — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Jamaal Bowman, Cori Bush, Betty McCollum and Marie Newman. Since they are widely known for their pro-Palestinian orientation, their endorsement was fully expected.

Tlaib’s support for the “right of return” has been an established fact since her espousal of a one-state solution. At one point, she supported a two-state solution, but abandoned that position a few years ago.

She must surely realize that her resolution stands absolutely no chance of success because it would effectively delegitimize Israel, a major ally of the United States. For this reason alone, it probably will not even be considered by the House of Representatives.

At best, it is a purely symbolic resolution designed to commemorate the nakba, heighten awareness of it in the United States, and publicize the Palestinian cause at a time when Israel has come under critical scrutiny by Americans.

Tlaib is well aware that U.S. official policy is invested in a two-state solution. This has been the case for decades now. Under no circumstances will the United States, within the foreseeable future at least, back the “right of return,” a code phrase for Israel’s piecemeal destruction.

The mass resettlement of Palestinian refugees and their descendants in Israel is simply a non-starter and has been since the 1948 war. Israel, conceivably, might one day allow a very limited number of refugees to go back, but this is a concession that would only be offered within the framework of a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.

For now, this rosy scenario lies far off in the hazy distance partly because Israel, to its long-term detriment, prefers conflict management to conflict resolution.

Tlaib should also bear in mind that the refugee problem would not have arisen in the first place had the Palestinian leadership in 1947 accepted the United Nations Palestine partition plan. The majority of Jewish leaders in Palestine embraced it as a pragmatic compromise, but Palestinian leaders adamantly rejected it in the hope that Arab armies would quickly snuff out the new Jewish state and push its Jewish inhabitants into the Mediterranean Sea.

The Palestinian refugee issue is a human tragedy, an oozing sore in geopolitical terms, and should be settled once and for all. But Israel alone cannot bear full responsibility for its successful resolution. This is a complex imbroglio that the Palestinians, the Arab world and the international community must jointly address.

Tlaib’s unrealistic resolution merely scratches the surface of a tragic and iconic issue that has yet to be settled.