Hezbollah and its allies lost their parliamentary majority in Lebanon’s May 15 election, but Hezbollah remains a potent and potentially destabilizing force in Lebanese politics as well as a major threat to Israel.

Four years after the last election, Hezbollah, backed by Iran and largely supported by the Lebanese Shi’a population, managed to regain its 13 seats in the 128-seat parliament. Its Shi’a ally, Amal, scooped up 27 seats.

Hezbollah’s Christian ally, the Free Patriotic Movement, of which Lebanese President Michel Aoun is a leader, suffered losses. As a result, the Hezbollah bloc won a total of 61 seats, four short of a majority, compared to 71 seats in 2018.

The Lebanese Forces, a Christian party led by former warlord Samir Geagea and an opponent of Hezbollah, picked up 22 seats.

Independent/reformist parties and political newcomers won 14 seats.

The election results were indicative of the voters’ disillusionment and discontent with the ruling elite, which is widely regarded as hopelessly corrupt and inefficient and is blamed for the country’s profound economic woes.

Since 2019, the majority of Lebanese have fallen into poverty, their savings wiped out by an astronomical inflation rate of over 200 percent. According to the World Bank, Lebanon’s economic collapse is one of the world’s worst since the mid-19th century.

The Lebanese government is equally blamed for the massive explosion in the summer of 2020 that virtually levelled the port of Beirut and killed more than 200 people. Previous governments were repeatedly warned that inappropriately-stored explosives, probably owned by Hezbollah, were a clear and present danger to the capital city, but the warnings were played down or ignored.

Lebanon’s economic crisis emboldened and empowered reformers. They won only one seat in 2018, but in the latest election they acquired about 10 percent of the parliamentary seats.

On the other hand, the disillusionment of the electorate with the political process was such that election turnout was only 41 percent, eight points lower than four years ago.

Amos Gilad, the executive director of the Institute for Policy and Strategy at Reichman University in Israel, spoke to this reality. “The Republic of Lebanon is a destroyed state,” he told the Israeli online newspaper The Times of Israel. “The government is paralyzed, the state is corrupt. And these elections don’t help in any way. No one can effect any change in (Lebanon), which is suffering from a terminal disease.”

Gilad, in his grim appraisal, was presumably alluding to Hezbollah. Although it does not wield the same political clout as in recent years, it is a powerful force that abides by its own rules.

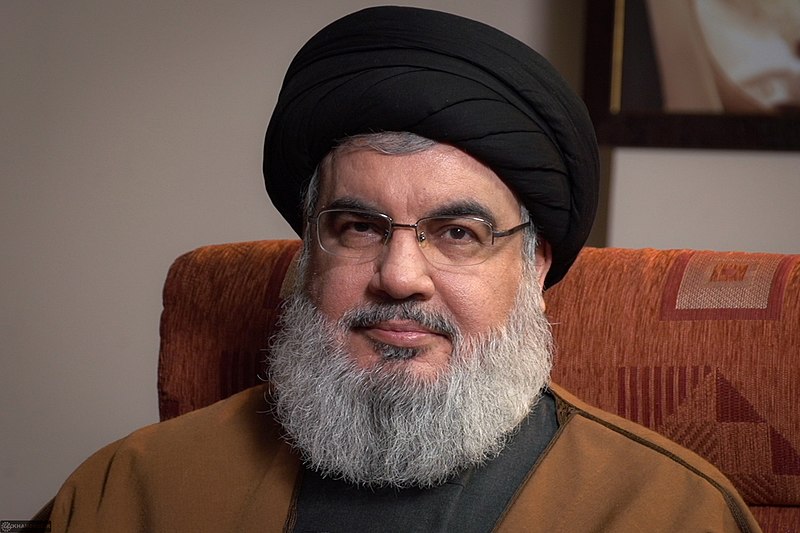

Hezbollah, after its last war with Israel in 2006, was required to surrender its arms under a United Nations resolution that ended the fighting. But Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, refused to do so, leaving Hezbollah as a state-with-a-state within the sectarian Lebanese system.

Like the PLO prior to Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Hezbollah has a free hand to launch occasional attacks against Israel, thereby dragging Lebanon into armed confrontations with Israel and destabilizing it.

Hezbollah gained a measure of popularity by forcing the Israeli army to withdraw from southern Lebanon in 2000. But since then, Hezbollah has antagonized some Lebanese, particularly Maronite Christians, by its confrontational approach to Israel.

In the past few years, Hezbollah has sent scores of drones into Israeli territory, some of which have returned to Lebanon unscathed. The most recent drone, shot down by Israel on May 17, was launched as the Israeli army conducted Chariots of Fire, a drill designed to prepare Israel for a major clash or war with Hezbollah.

Israeli drone flights into Lebanon are not uncommon, but according to Nasrallah, they have been “greatly reduced” due to Hezbollah’s improved air defences.

For precisely this reason, the Israeli Air Force no longer has unfettered freedom of action in Lebanon, its former commander, Amikam Norkin, admitted last month. Consequently, Israel has reduced its surveillance flights in Lebanon, damaging its intelligence-gathering capabilities.

By virtue of its stockpile of 150,000 rockets, some of which have been adopted for precision strikes at Israel’s infrastructure and Israeli military bases, Hezbollah must be taken seriously by Israel. In the 2006 war, Hezbollah fired 4,000 rockets at Israel.

Hezbollah, too, has inserted itself into Lebanon’s on-again, off-again negotiations with Israel over the still unresolved maritime border.

Last October, Nasrallah warned Israel against unilaterally searching for natural gas in disputed areas. And earlier this month, he rejected Israeli-born U.S. diplomat Amos Hochstein as a mediator. “I am saying to the Lebanese state: If you want to continue negotiating, go ahead, but not with Hochstein, Frankenstein, or any other Stein coming to Lebanon.”

Whether Hezbollah will be sufficiently powerful to make such demands following last week’s election has yet to be determined.

In the meantime, voters in Lebanon can expect months of protracted negotiations before the next government is formed and a new prime minister and a new president are appointed.

As the American Task Force on Lebanon said in a press release on May 18, “Many analysts point to gridlock as the next possible inhibitor of progress. There will be obvious sources of division not only between Hezbollah and its opponents, but also from the political newcomers and reformists who have yet to form their own bloc. Importantly, no coalition has been formed that can govern with a parliamentary majority. and it is unclear how long the formation of such a coalition will take.”

In other words, the future of Lebanon hangs in the balance.