The displacement of some 700,000 Palestinians from their homes in what is now Israel, an event known as the nakba, has been a topic of international concern for more than seven decades now. During and after this upheaval, close to 850,000 Jews in the Arab world and Iran left or were compelled to leave their homes. To the outside world, their plight is more or less buried in obscurity.

Intent on telling their story, Henry Green, a professor of religious studies at the University of Miami, formed Sephardi Voices, an audio-visual digital archive of Arab Jews.

He and Richard Stursberg, a Canadian author and chairman of Sephardi Voices International, have written Sephardi Voices: The Untold Expulsion of Jews From Arab Lands (Figure 1 Publishing), a lavishly-illustrated account of this mass movement.

The title is misleading, as scores of books, monographs and newspaper and magazine articles have been published about this subject. Yet Sephardi Voices, transmitting the experiences of Jews who lived in the Middle East during this turbulent period, is a worthy addition to this collection.

Their flight, to the authors, is not just a tale about vanished Jewish communities, but a narrative about the infringement of human rights.

Jews in droves left the region not only because of the birth of Israel and the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli conflict, but because state-sanctioned discriminatory policies and street violence forced them to depart.

“Their Muslim neighbors turned against them,” they write. “Their governments seized their property, imprisoned their leaders, stripped them of their citizenship, and forced them to flee … to become refugees in North America, Israel and Europe.”

The Sephardi Jews profiled in this handsome coffee-table volume trace their roots to the Iberian Peninsula, from which they were expelled in the late 15th century, and the Mediterranean basin, to which they fled after foreign invasions of their ancestral home in the Land of Israel.

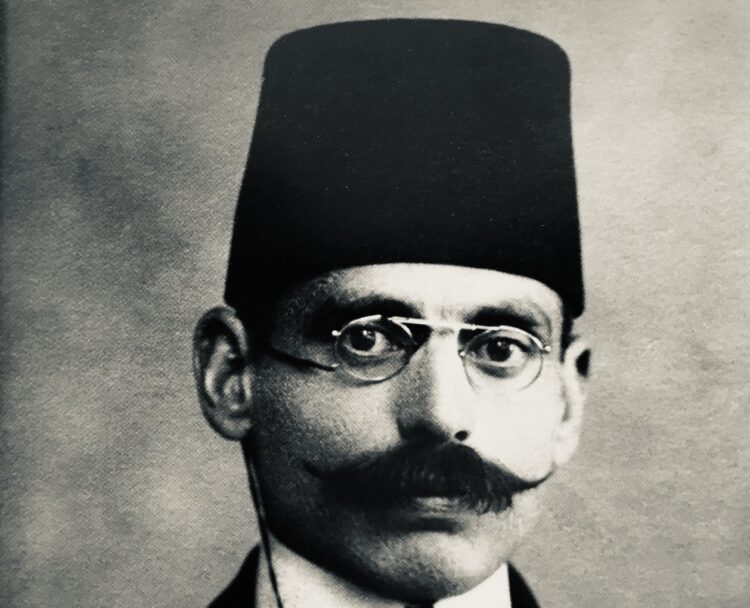

As they remind us, Jews in the Islamic world were considered dhimmis, or People of the Book entitled to legal protection. As second-class citizens, they were forced to pay a special tax, the jizya, and were subjected to an array of restrictions, which were enforced to varying degrees in different times and places.

Jews in Muslim Spain prospered, but in Mamluk Egypt, dhimmi regulations were vigorously observed. In the Ottoman Empire, centered in Constantinople, their status as dhimmis remained in force, but they were permitted to manage their communities and own property. With the Tanzimat reforms in the last quarter of the 19th century, Ottoman Jews enjoyed full civil rights.

In Arab lands, Jews were virtually indistinguishable from Muslims in terms of language, culture, clothing and food.

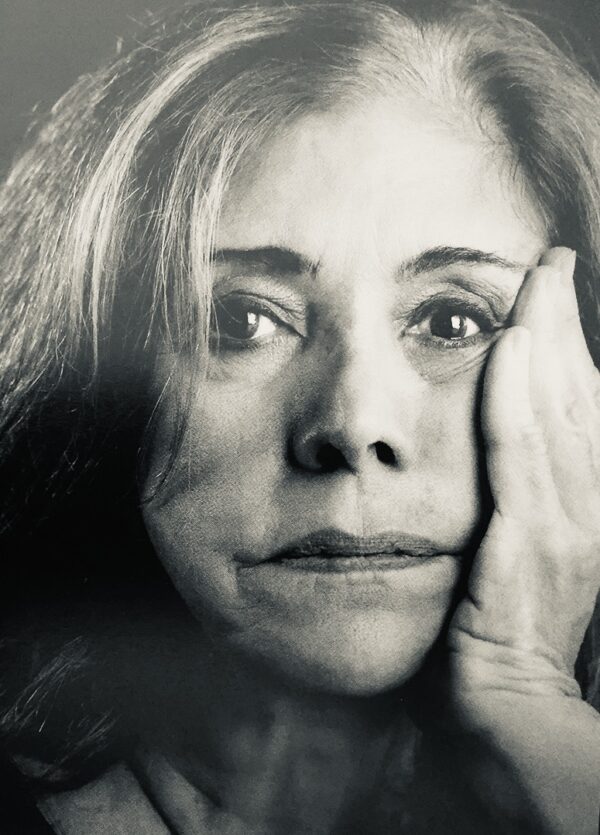

Egyptian Jews, concentrated in Cairo and Alexandria, generally prospered. “My best friend was a Muslim from an Egyptian aristocratic family,” says Levana Vidal Zamir, who was born in Cairo in 1938 and immigrated to Israel in 1950.

By 1956, almost half of Egypt’s 80,000 Jews had emigrated, having endured a skien of hardships. Juliette Akouka Glasser, who escaped to the United States in 1959, is still wracked by nightmares.

The relationship between the state and Jews deteriorated after the mid-1950s Lavon affair, during which Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser cracked down on the Jewish community after local Jews acting as Israeli agents planted bombs at British, French and Egyptian locales.

By 1968, nearly every Jew had left Egypt. Andre Aciman, who would become a novelist and literate critic, emigrated in 1964 at the age of 13.

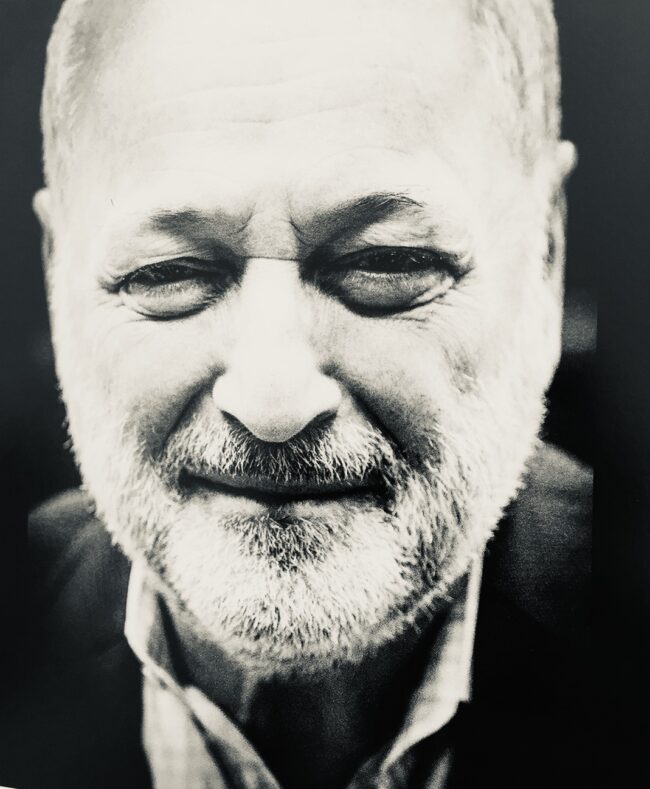

Until 1948, Iraq had the second largest largest Jewish community in the Middle East after Morocco. Two hundred Jews were killed in a pogrom in Baghdad in 1941, but as the authors write, Iraqi Jews were well off, comprising “much of Iraq’s industrial, commercial and financial sectors. They were central to its economic growth and prosperity, and became integrated into the social, political and cultural life of the country.”

“At the (horse) races, my father with his Muslim friends sat in his box next to the king,” recalls Lisette Shashoua Ades, who was born in 1948 and arrived in Canada with her family in 1970.

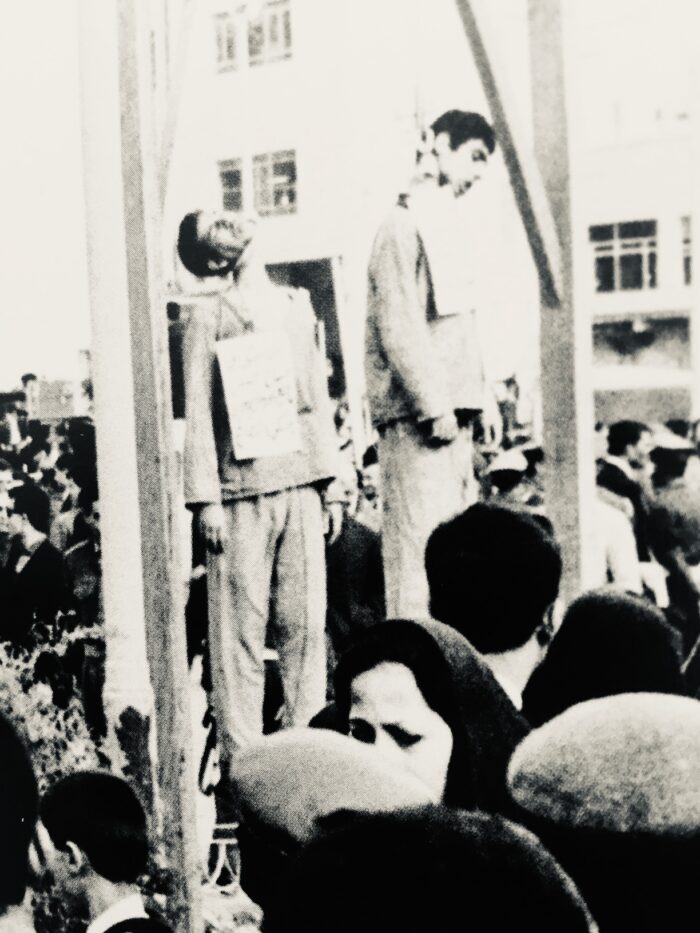

Restrictions on Jews were lifted after the fall of the Baath Party from power in 1963. But after the 1967 Six Day War, the Baath returned and the remaining 5,000 Jews felt the sting of discrimination. In 1969, several Jewish men accused of espionage were hanged in Baghdad’s central square. The day was declared a national holiday by the venal Iraqi regime.

Morocco was home to 250,000 Jews in the 1940s, but in the intervening decades they emigrated, leaving less than 4,000 today. Moroccan Jews, in the main, have immigrated to Israel, Canada and France.

They have usually done well abroad. Aldo Bensadoun founded the Aldo Group in Montreal, a huge footwear designer, manufacturer and distributor. Paul Marciano established Guess Jeans, which sells a line of clothing, swimwear, watches and sunglasses.

Libya, with the smallest Jewish community in North Africa, had 25,000 Jews in the 1930s. Two-thirds lived in Tripoli and Benghazi. Pogroms broke out in 1945. Still more violence erupted in the following years. Muammar Gaddafi, the new ruler, arrested Jewish men, confiscated their property, froze Jewish bank accounts, closed synagogues and razed Jewish cemeteries.

Following the passage of the United Nations 1947 Palestine partition plan, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Syria. Further restrictions were placed on Jews after Israel conquered the Golan Heights in 1967, and Jews were forbidden to emigrate. The last 4,000 were finally allowed to leave in 1991.

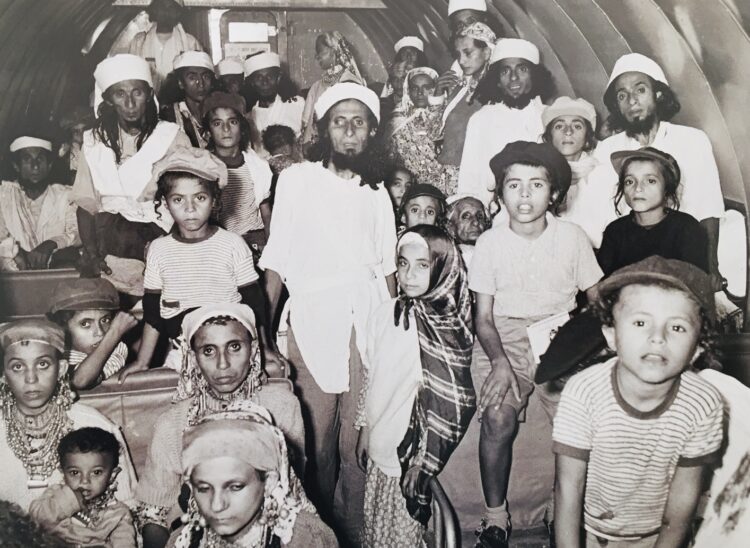

Jews in Yemen were well established, but their lives were circumscribed by dhimmi restrictions. As the authors note, “They had to wear special clothes, and could not build houses bigger than their Muslim neighbors.” Only Jews in Aden, controlled by Britain, lived reasonably normal lives. Israel airlifted the majority of Yemen’s 50,000 Jews in the early 1950s.

Of the 900,000 French citizens who emigrated from Algeria, 125,000 were Jews. Among them was Jacques Derrida, who would be an influential philosopher.

Green and Stursberg estimate that the assets lost by Middle Eastern Jews are worth the equivalent of more than $100 billion, roughly the size of the economies of Yemen, Iraq and Tunisia combined. Yet they have never been compensated for their losses by Arab governments.

“The sad truth is that Arab countries have never come to grips with their lamentable treatment of their own citizens,” they write. “Unlike Germany addressing its Nazi past, there has been no effort to pursue a policy of truth and reconciliation … and make amends.”

Iran, a Persian Muslim state, is mentioned relatively briefly. For centuries, Jews were hemmed in by dhimmi rules, the authors say. “This changed dramatically in 1926, when the shah took power and abolished the jizya, granting all subjects equal rights.” But after the 1979 Islamic revolution, Jews gradually left Iran. Nonetheless, Iran is home to the largest Jewish community in the Muslim world.