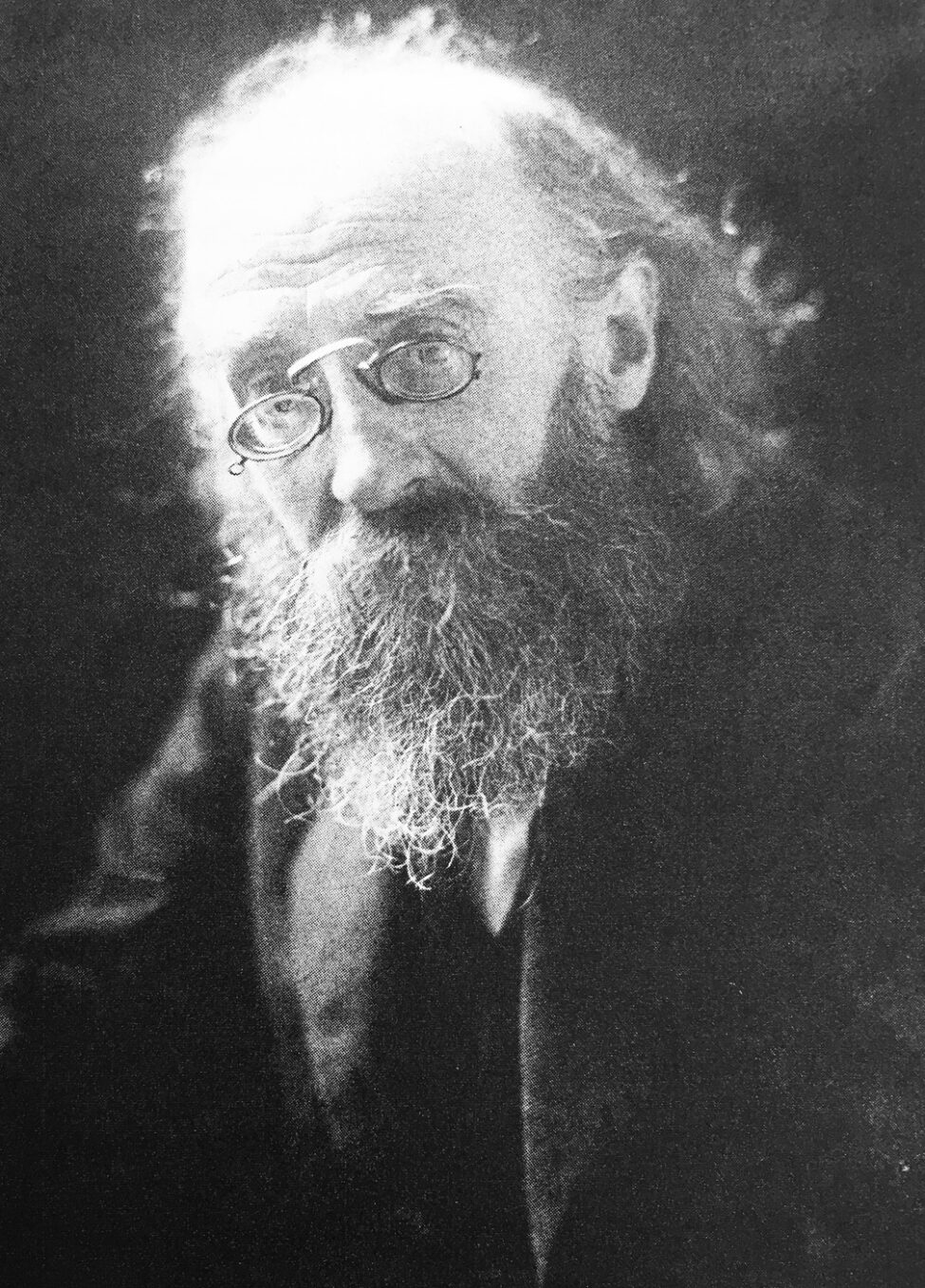

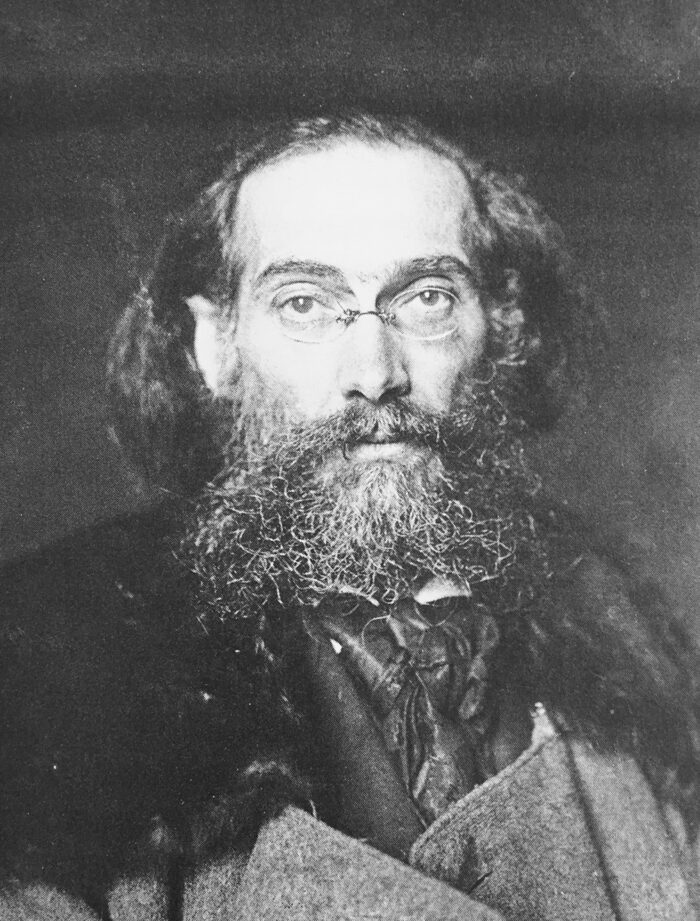

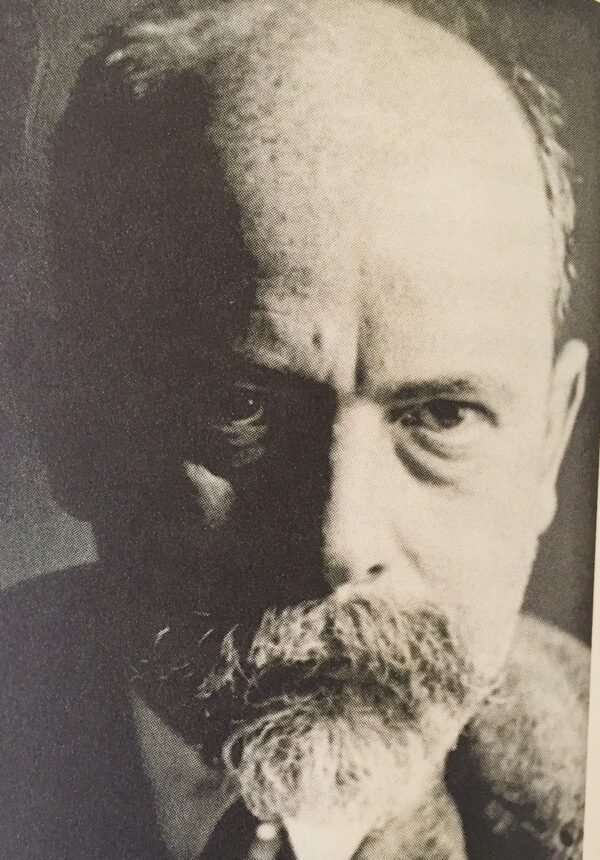

Shortly after Germany’s defeat in World War I, a Munich-based Jewish socialist/journalist named Kurt Eisner toppled the venerable Wittelsbach dynasty, formed the short-lived Free State of Bavaria, and became the first Jew ever to govern a German state. On February 21, 1919, three months after his accession to power, he was assassinated by an antisemitic gunman of Jewish ancestry.

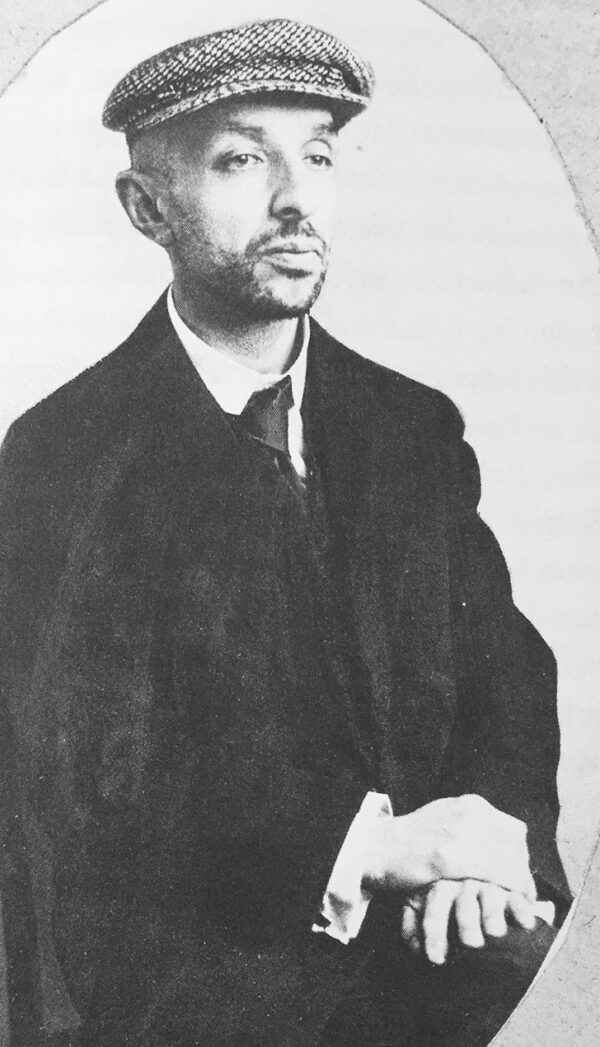

Eisner’s Jewish friend, Gustav Landauer, met a similar fate. An anarchist, Landauer was a minister in another fleeting left-wing republic, established in Munich two months after Eisner’s death. He was killed by extremists on May 2, 1919.

Michael Brenner, a professor of Jewish history and culture at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, has written a comprehensive and fascinating book about this nearly forgotten turbulent period. In Hitler’s Munich: Jews, The Revolution, and the Rise of Nazism (Princeton University Press) is about Jewish revolutionaries, antisemites, an intimidated Jewish community, and the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement.

By any measure, these revolutionary upheavals in Munich were momentous. Hitler, in his manifesto Mein Kampf, linked “the rule of the Jews” to his political awakening and entry into politics.

In staunchly conservative circles, the conspicuous prominence of Jewish leftists in the revolutions irretrievably branded Jews as subversives and insurrectionists, despite the fact that the vast majority in Munich usually voted for centrist bourgeois parties and vehemently disagreed with the Jewish revolutionaries’ ideology and policies.

Needless to say, Eisner and Landauer were not the only Jews who participated in the failed revolutions that a shook Germany to its core in 1918 and 1919. Felix Fechenbach was Eisner’s private secretary. Edgar Jaffe, a convert to Christianity, served as Eisner’s finance minister. Eugen Levine was Landauer’s associate.

As Brenner points out, the Jewish revolutionaries were, in Isaac Deutscher’s famous phrase, non-Jewish Jews, though some were attached to their Jewish cultural heritage. They were part of a group of European Jews who tilted to the far left — Leon Trotsky in Moscow, Rosa Luxemburg in Berlin and Bela Kun in Budapest — and attempted to create a new order.

Prior to 1918, German Jews who ventured into politics were party functionaries and members of parliament. But during the revolutionary fervor in Munich, Jews, having been fully emancipated in 1871, were “suddenly showing up in leading government posts … and determining the fate of the nation,” says Brenner.

There was an antisemitic backlash, of course, and Jews en masse were identified with the revolutions “without having had a hand in the matter.” As he observes, Munich Jews ruefully remembered the saying from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution about Trotsky, whose real surname was Bronstein: “The Trotskys make the revolution, and the Bronsteins pay the price.” Which is precisely why the philosopher Martin Buber referred to the events in Munich as “an unspeakable Jewish tragedy.”

The Jews of Munich, a cosmopolitan city in southern Germany, were generally loyal supporters of the 700-year-old Wittelsbach monarchy. By 1910, 11,000 Jews lived in the city, one-quarter of whom were newly arrived Ostjuden from the Russian empire.

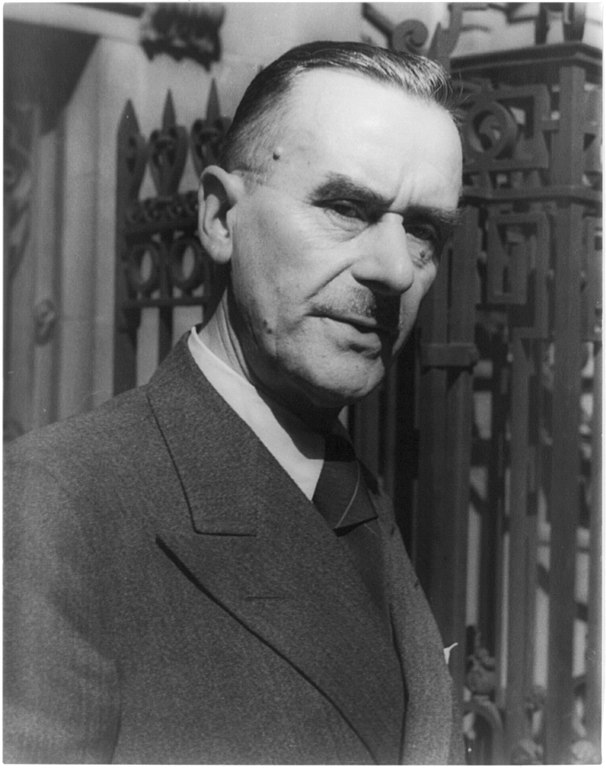

Munich was also home to renowned writers and artists such as Thomas Mann and Franz von Stuck, who burnished its reputation as a glittering cultural center.

Yet, as Brenner notes, the first openly antisemitic organization in Germany was founded in Munich, and anti-Jewish groups like the Thule Society and the Freikorps, a paramilitary outfit, had branches there. The German Fatherland Party’s branch in Munich boasted of a membership that included rabid antisemites like the widow of the composer Richard Wagner, the philosopher Houston Stewart Chamberlain, and the founder of the forerunner of the Nazi Party, Anton Drexler.

The so-called “Jewish Question” loomed large in Munich’s right-wing press, which branded Jews as communists, war profiteers and “alien elements.”

The Bavarian prime minister, Gustav von Kahr, turned a blind eye to this rampant hatred, and the top figures in Munich’s police force were among the earliest recruits of the Nazi Party.

According to Brenner, Munich became the center of the Nazi movement and the capital of antisemitism in Germany. In 1923, the year of Hitler’s failed Beer Hall putsch, Mann proclaimed it as “the city of Hitler.” By that juncture, Munich’s Jewish population had fallen to 9,000, and Jewish travellers were urged to avoid Bavaria.

A deeply conservative Catholic state, Bavaria seemed the last place in Germany where a bloodless revolution would rear its head.

Eisner, a Social Democrat from an assimilated Berlin family, believed that antisemitism would disappear in a socialist society. The public mood, as reflected in a diary entry by Munich’s archbishop, Michael Faulhaber, was dismissive of this naive supposition. “What does this Jew have to do with us?” the cleric wrote scathingly of Eisner, some of whose cabinet ministers were old school moderates.

Eisner’s close confidant, Landauer, a fellow Berliner, was the people’s commissioner for public education, instruction, science and arts in the first Council Republic of Bavaria. When it was replaced by a more doctrinaire version of itself, Landauer resigned. Soon arrested by the Freikorps, he was murdered in his prison cell. In Brenner’s estimation, they were among the first victims of Hitler’s “long and twisted road to power.”

Jews like Landauer and Eisner were particularly despised by far right nationalists like Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, who killed Eisner. Valley, whose mother, Emmy von Oppenheim, was Jewish, condemned Eisner as a “Bolshevik” and a “Jew.”

Valley’s antisemitic ravings did not impress the Thule Society, which refused to admit him as a member due to his partial Jewish ancestry. Despite his “tainted” racial profile, he survived the Nazi era, and died in a car accident shortly after World War II.

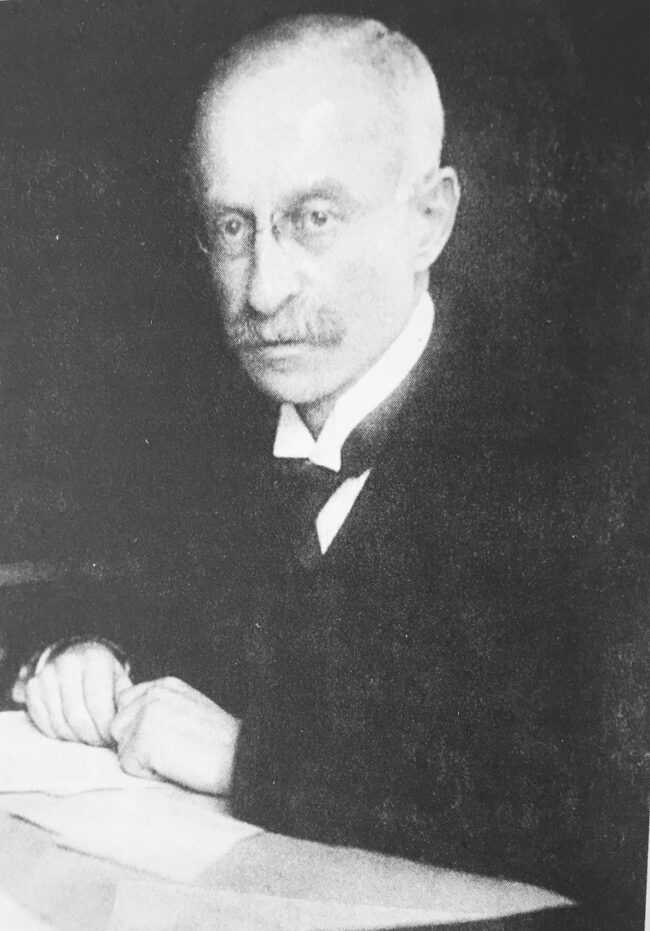

Another self-hating Jew listed by Brenner was Paul Niklaus Cossmann, a newspaper editor who was instrumental in creating the notorious “stab in the back” myth, which claimed that Germany was defeated not on the battlefield but at home by internal enemies running the gamut from socialists and liberals to trade unionists and Jews.

Unlike Valley, Cossmann’s fascist worldview failed to protect him from the wrath of the Nazis. With the deportation of Munich Jews in 1941, Cossmann was taken to a holding camp nearby and then sent to the Theresienstadt camp, where he died shortly after arrival in 1943.

By that point, Munich, with its extensive network of antisemitic organizations and newspapers, had fully morphed into Nazi Party headquarters. “Munich became Hitler’s city owing to an environment that was extremely favorable to him and his movement,” says Brenner.

In 1923, the U.S. acting consul in Munich, Robert Murphy, reported that the Bavarian prime minister was “decidedly anti-Jewish” and was of the opinion that “Jewish elements in Germany (were) responsible for much of (Germany’s) misfortune and economic distress since the war.”

Hitler attended the first meeting of the German Workers’ Party, soon to be renamed the Nationalist Socialist Party, in Munich in 1919. And he delivered his first speech there.

Such was the openly antisemitic mood in Munich that a Jewish delegation notified the state government in 1922 that “our existence in Germany … is called into question.”

Shortly afterward, Germany’s first Jewish foreign minister, Walther Rathenau, was assassinated by antisemitic thugs whose organization was based in Munich.

Munich, as Brenner grimly writes, was “a stage for Hitler” and “the ideal laboratory” for his growing Nazi movement.