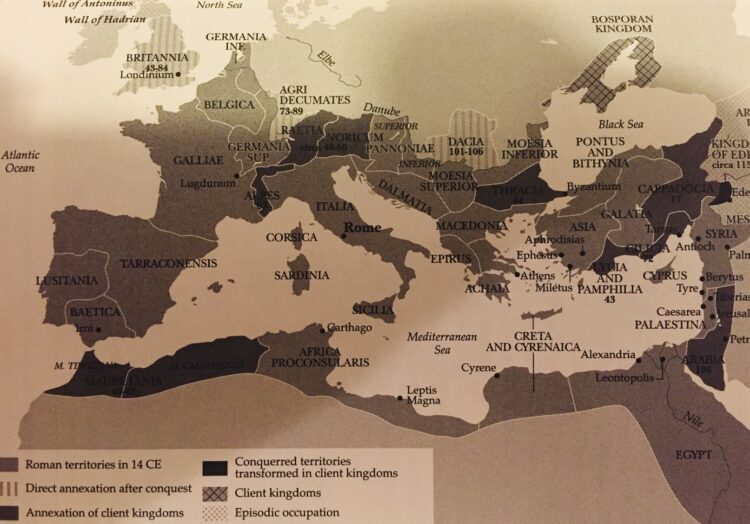

Jews in ancient Israel lived under a succession of foreign imperial invaders ranging from the Egyptians and the Assyrians to the Babylonians and the Persians. But as Katell Berthelot argues in Jews And Their Roman Rivals: Pagan Rome’s Challenge To Israel (Princeton University Press), the Roman Empire posed “a unique ideological challenge for Jews ”

Berthelot’s illuminating book covers the period from the second century BCE to the fourth century CE, during which three Jewish uprisings erupted in 66-73, 115-117 and 132-135 CE.

As Berthelot, a professor of ancient Judaism at Aix-Marseille University in France, points out, “no other people within the Roman provinces revolted on such a large scale.”

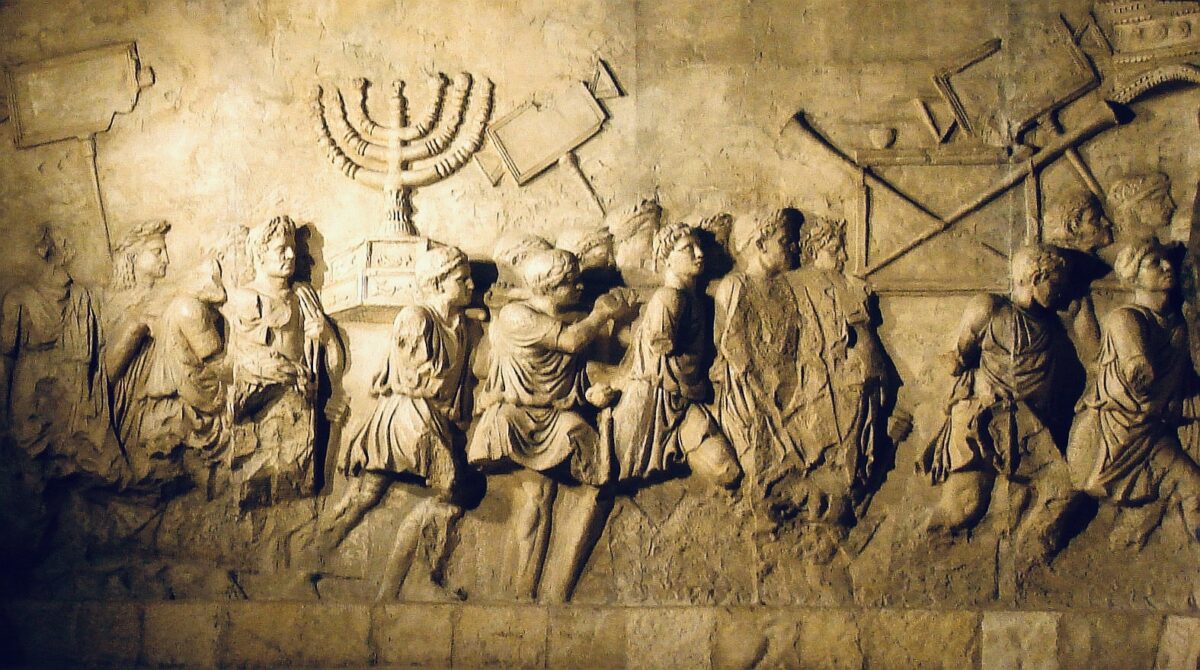

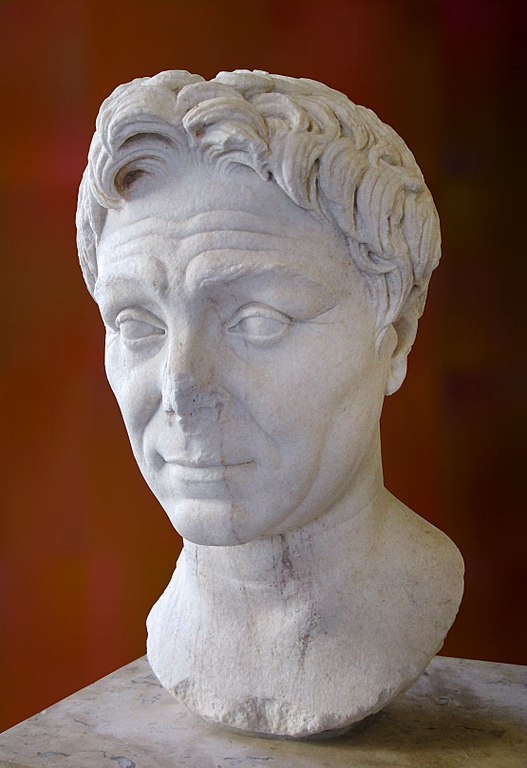

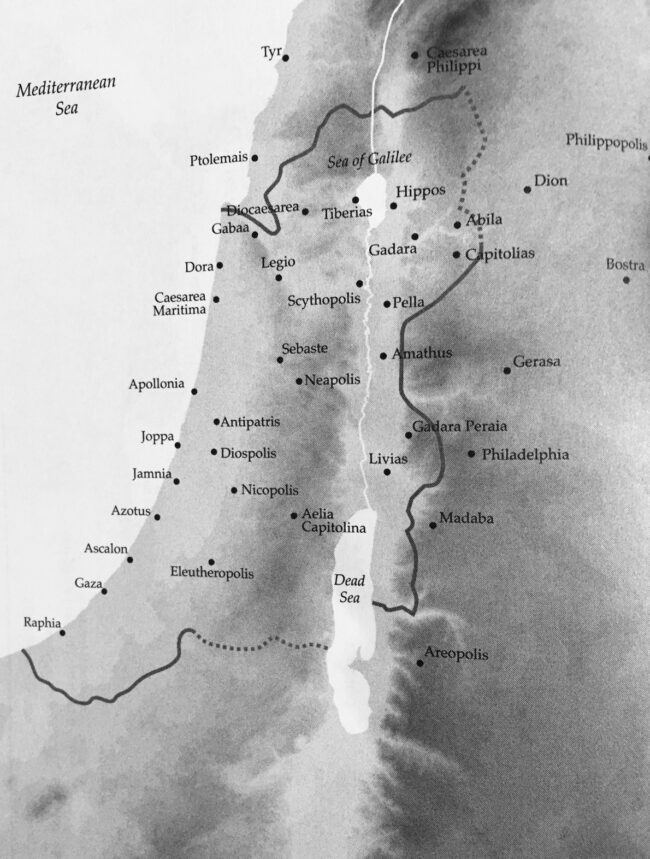

During the course of these revolts, the Roman general Pompey conquered Judea, the Judean desert fortress of Masada fell to Rome, Jerusalem was captured and renamed, Judea was rebranded as Palaestina, and the monumental Arch of Titus was built in Rome to commemorate Rome’s victory over Jews.

The demise of Jewish sovereignty in Judea in 63 BCE, echoing the Assyrian destruction of the northern Kingdom of Israel in 722-720 BCE and the Babylonian demolition of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in 587 BCE, had a major effect on Jewish perceptions of Rome, she writes.

The problem grew more acute after the Romans established direct rule in Judea in 6 CE and after Rome was transformed from a pagan into a predominantly Christian empire.

As she notes, the failure of all three revolts had devastating effects. Many Jewish lives were lost. A great number of Jews were enslaved. Lands were confiscated. The Jewish population of Judea was virtually emptied. The temple was destroyed and Jerusalem was refounded under the name of Aelia Capitolina.

Under the Romans, Jews lost their political independence, witnessed the occupation of their land and were subjected to taxation. “It was an unhappy situation but in the main a familiar one, very like what they had experienced in centuries past,” she says.

In explaining why Rome presented a challenge of such magnitude to Jews, Berthelot quotes the Jewish scholar Gerson Cohen: “Each considered itself divinely chosen and destined for a unique history. Each was obsessed with its glorious antiquity. Each was convinced that heaven had selected it to rule the world. Neither could accept with equanimity any challenge to its claims.”

Berthelot believes that both the Romans and the Jews had “a clear sense a historical destiny.” Referencing the scholar Clifford Ando, she says that Roman law and jurisdiction were particularly challenging to Jews.

While some Jews were antagonistic to Rome, still other Jews accommodated themselves to Roman domination. “Beginning no later than the first century BCE, some Jews were granted Roman citizenship … Jews contributed to the formation of Roman imperial culture, together with other ethnic groups.”

Among the most prominent Jews coopted by the Romans were Josephus, the historian and author of The Jewish War, and Herod the Great, whose father, Antipater, was granted Roman citizenship by Julius Caesar as a reward for his military support during a war in Egypt.

Roman leaders basked in the glow of their willingness to include conquered people in their community, but as Berthelot observes, “it is far from certain that all provincials viewed this universalist ideology positively.”

In addition, a number of well-known Roman authors, including Cicero and Tacitus, claimed that many Romans perceived Jews as a superstitious and even an impious people.

By sharp contrast, Palestinian rabbis considered Jews as the most pious people on the face of the earth and rejected the notion that Roman victories on the battlefield were rewards for the Romans’ piety toward the gods.

Bertholet’s book, a work of erudite scholarship, opens new vistas into an understanding of the events and dynamics that shaped Rome’s relationship with Jews over several centuries.