An inflection point in American history, the U.S. Civil War erupted less than a century after the formation of the United States. Resulting in the deaths of 620,000 soldiers, or six million by today’s calculation, it was the costliest war ever waged by the United States.

Breaking out in 1861 and ending in 1865 with the surrender of the secessionist Confederacy, it affected virtually every ethnic and religious community in the country.

Jewish Americans fought for the Union in the north and the Confederacy in the south. By most accounts, 6,000 Jewish soldiers served the north, while upwards of 3,000 joined the ranks of the south, according to Jews and the Civil War: A Reader (New York University Press), an illuminating book of essays edited by Jonathan Sarna and Adam Mendelsohn.

Comprehensive in scope, it covers a full range of topics: the Jewish foot soldiers and officers who sacrificed their lives for their respective causes, the Jewish communities in the north and the south that sent warriors into the battlefields, the Jews whose businesses were bound up with slavery, and the antisemitism that emerged in and out of the military.

With a population of 31 million, the United States was home to about 150,000 Jews when the war started. During this era, the majority of Jews in America were new immigrants, mostly from the Germanic states.

Jews, whether native-born or immigrants, were swept up by the tide of patriotism. As Eli Evans writes in the introductory essay, “Jewish families with sons from cities and towns all across the country were involved in the Civil War.”

Jews from every walk of life enlisted, though some, like West Point graduate Major Alfred Mordecai, were torn in terms of their loyalty.

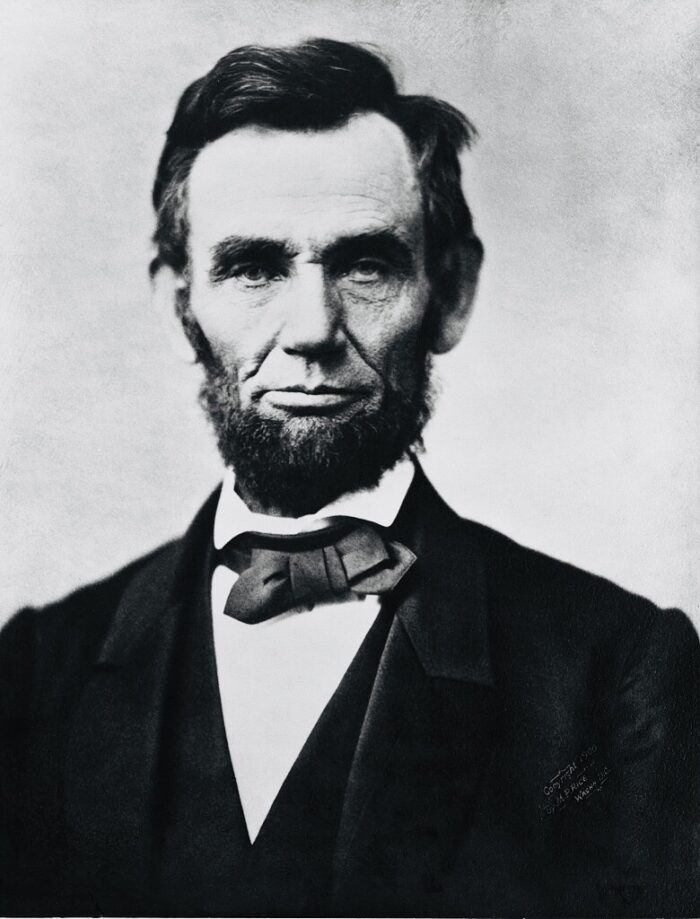

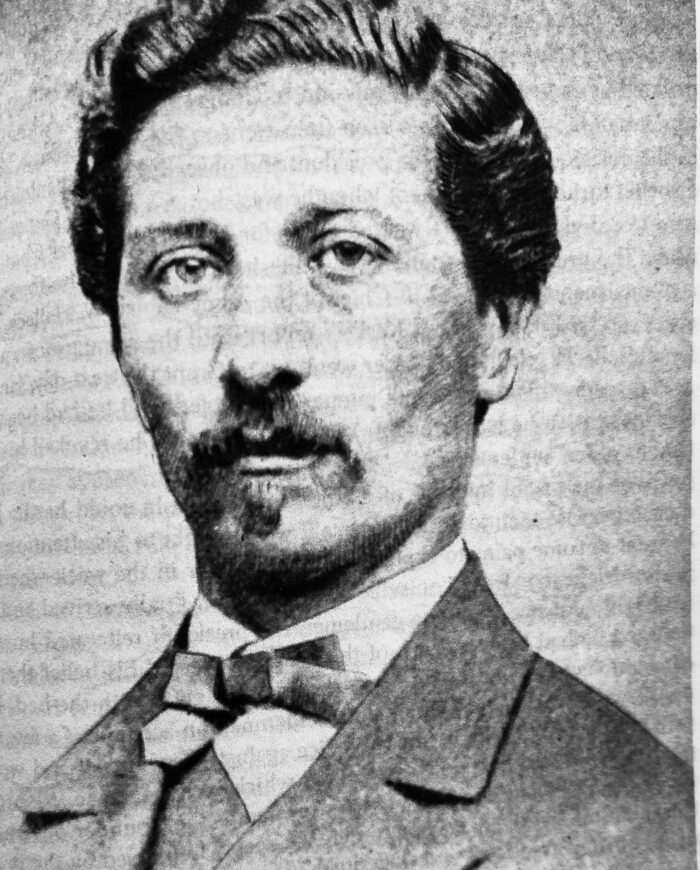

Julius Ochs, a southerner from Tennessee and the father of the man who would buy and run The New York Times, joined the Union army. Leopold Karpeles, a sergeant who immigrated to the U.S. from Prague in 1851, received the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery in battle, one of six northern Jews who won the nation’s highest award. Issachar Zacharie, President Abraham Lincoln’s closest Jewish friend, was assigned to the task of exploring the prospects of peace with the Confederacy.

Frederick Kneffler, a Hungarian Jew who arrived in the U.S. two years before the war, attained the rank of major general. He and Edward Solomon, a brigadier general, were the two highest ranking Jews on the Union side.

Jews attained a measure of prominence in the Confederacy.

Judah Benjamin, the first acknowledged Jew in the U.S. Senate, was its attorney general, secretary of war and secretary of state. Evans claims that Benjamin “achieved greater political power than perhaps any other Jewish American in history.” He is probably correct.

Henry Hyams was the lieutenant governor of Louisiana and Dr. Edwin Moise was the Speaker of that state’s legislature. David Lopez, an architect, designed a boat that, in 1863, took part in the first successful torpedo attack in naval history. Colonel Abraham Charles Myers, a West Point graduate and the great grandson of a rabbi, was the quartermaster general of the Confederate army.

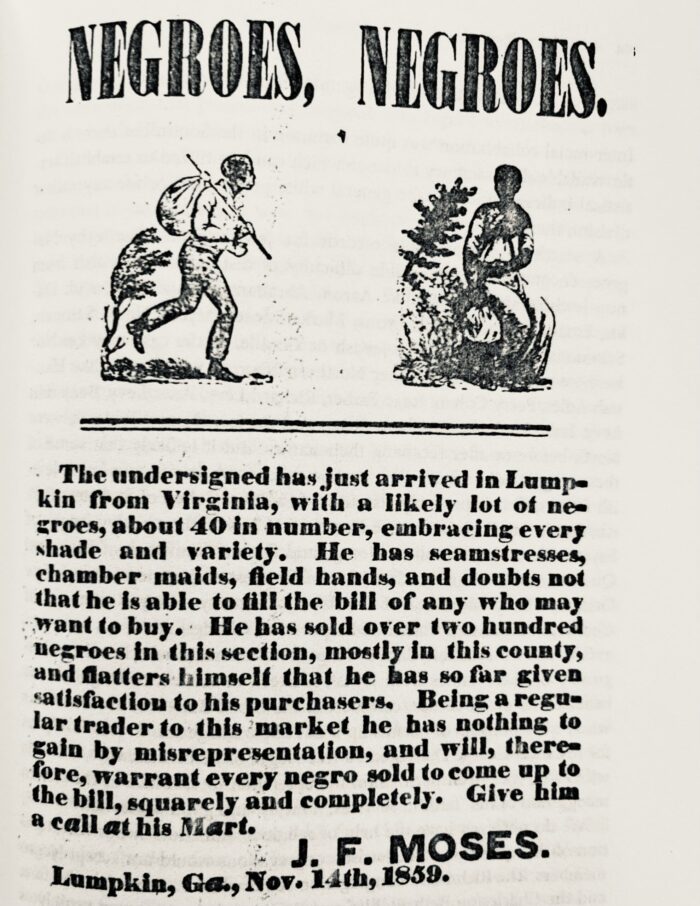

The issue of slavery, one of the causes of the war, is explored by Seymour Drescher. His conclusion is that Jews were marginal participants in the slave trade, but that the Christian descendants of Jews played a greater role in it.

When the Civil War began, there were Jewish communities in southern cities such as New Orleans, Charleston, Savannah, Atlanta, Memphis and Nashville, Robert Rosen writes. By his estimate, 20,000 to 25,000 Jews lived in the eleven states comprising the Confederacy.

In another essay, Bertram Korn notes that only a small number of Jews in the antebellum south, including Judah Benjamin, owned plantations with slaves. The average southern Jew was not as prosperous, invariably earning a living as a peddler or storekeeper.

Yet, as Korn observes, Jews “participated in every aspect” of slavery and did not express reservations about it. Indeed, Benjamin was regarded as “one of the most eloquent defenders of the Southern way of life.”

Despite their patriotism, Jews were maligned by antisemites.

The southern press occasionally depicted Jews as unpatriotic “scavengers.” The northern press sometimes portrayed them as cunning speculators. In both cases, Jews were convenient scapegoats for the social and economic ills of the day.

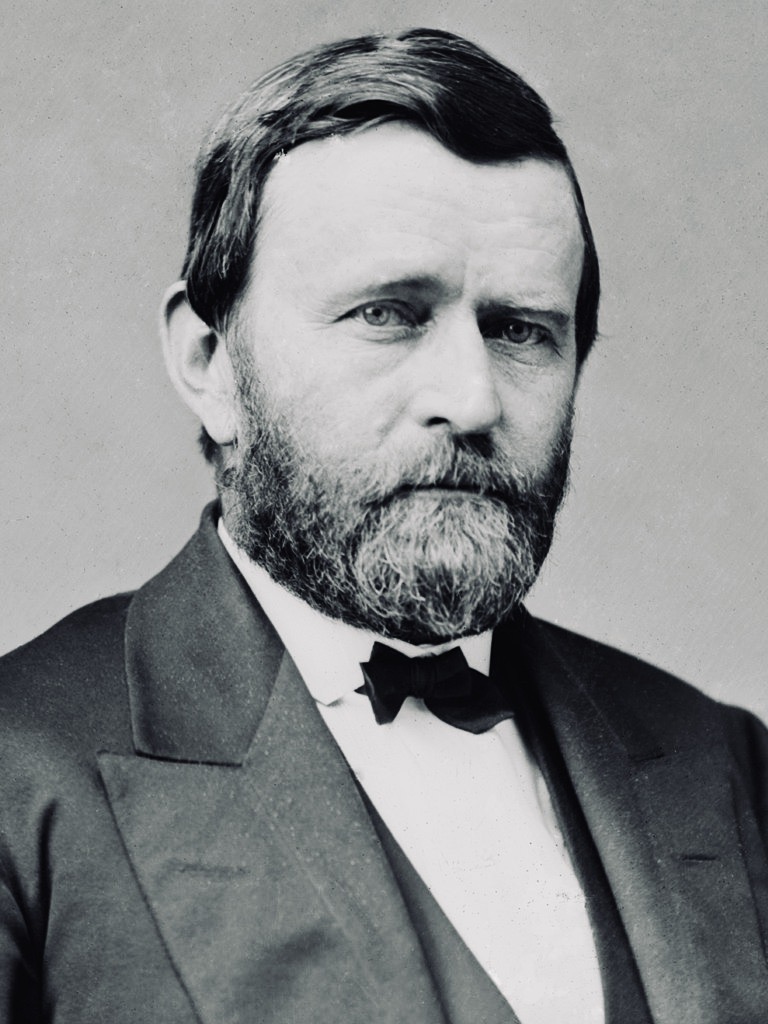

By far the most notorious antisemitic incident of the war occurred on December 17, 1862, when Union General Ulysses S. Grant issued Order Number 11, which expelled “Jews as a class” from sections of Tennessee, Mississippi, Kentucky and Illinois. Grant resorted to this drastic step in the belief that Jews were enmeshed in illegal cotton speculation in his area of command.

Cesar Kaskel, a merchant in Paducah, Kentucky, was so outraged by the expulsion order that he hastened to Washington to inform Lincoln of it. Having been unaware of it, Lincoln immediately instructed the highest ranking army general to cancel it.

Lincoln was also instrumental in the appointment of the first Jewish chaplain in the American armed forces. The appointee, Jacob Frankel of Philadelphia, was born in Bavaria and immigrated to the United States in 1848.

As for Grant, he was haunted by Order Number 11 when he campaigned for the presidency in the late 1860s. Although he never apologized or mentioned it in his memoirs, he claimed he was not prejudiced against any “sect or race” and judged people on their own merits.

During his term in office, as if to make amends, he appointed Jews to diplomatic positions and offered the post of secretary of the treasury to a Jewish banker.

Jews and the Civil War: A Reader is a valuable addition to American Jewish historiography, delving into a subject that is still sensitive and prone to a wide range of interpretations.

Nonetheless, the editors are remiss in several respects.

Order Number 11, as consequential as it was, appears and reappears throughout the volume. If these repetitions had been pruned, the narrative would have been more streamlined.

Southern Jewish communities are subjected to more scrutiny than their northern counterparts. And the biographies of high-ranking Jewish officers in the Union and Confederate armies should have been expanded to some degree.

Hopefully, these slips will be corrected in the next edition.