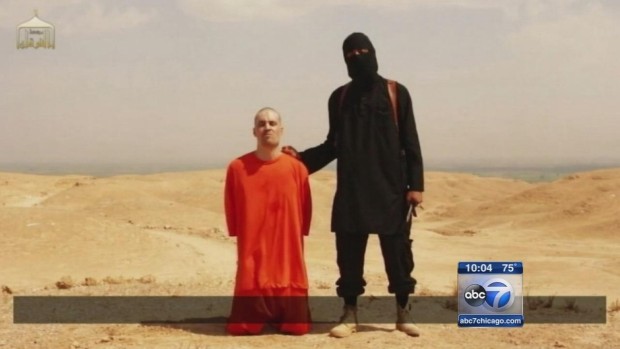

U.S. President Barack Obama finds himself on the sharp horns of a dilemma following the barbaric beheading of James Foley, an American freelance journalist, on Aug. 19.

Foley was the second American reporter since Daniel Pearl to be killed by crazed Islamic radicals. Foley was murdered by Islamic State, an extremist, bloodthirsty outfit bent on creating an Islamic religious state in Iraq and Syria and purging these countries of long-established Christian and Yazidi minorities.

Foley, taken hostage by IS in Syria in November 2012, was executed in Iraq in retaliation for a series of limited American air strikes on IS formations in Iraq. The United States, which pulled the last of its combat soldiers out of Iraq in December 2011, intervened militarily after IS, a spinoff of Al Qaeda in Iraq, captured the biggest dam in Iraq and advanced toward Erbil, the capital of the semi-autonomous Kurdish region.

Before killing Foley in cold blood, IS demanded a ransom of $130 million, but the United States, wisely, refused to pay. For the past few years, Al Qaeda and its regional affiliates have financed their operations by kidnapping European travellers and extorting hefty ransoms for their safe return.

Unwilling to play that loathsome and counter-productive game, the United States dispatched Delta Force commandos to northern Iraq recently in an attempt to free Foley and Steven Sotloff, another American journalist held by IS. The rescue mission, unfortunately, was not successful, and Foley paid the ultimate price. He was decapitated by an IS terrorist who spoke English with a British accent, confirming reports that hundreds of Europeans, mainly Muslims, have flocked to join the ranks of IS jihadists.

Since Foley was the first American citizen killed by IS, the United States took the incident with the utmost seriousness. Obama, who as a presidential candidate promised voters he would withdraw American troops from Iraq, declared that the United States would not end its current mission in Iraq until IS — a cancerous growth in Iraq’s body politic — is eliminated.

John Kerry, the U.S. secretary of state, was just as emphatic, saying that IS “must be destroyed.”

On Aug. 21, Gen. Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, added a new element to the equation by admitting that IS cannot be beaten unless the United States destroys its forces in Syria, which has been embroiled in a civil war since 2011. Asked whether the United States would bomb IS targets in Syria, U.S. Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel replied, “We’re looking at all options.”

The suggestion that Washington is considering an aerial bombing campaign in Syria places Obama in a very difficult position.

The Obama administration, having broken with the Syrian Baathist regime of President Bashar al-Assad over its violent repression of peaceful demonstrations calling for political change, has urged him to resign and supported mainstream rebels who seek his ouster.

Since then, the United States, in partnership with regional allies, has funnelled non-lethal aid to the rebels. Two months ago, however, the Obama administration requested $500 million from Congress to train and equip moderate rebel groups. The request represents a quantum leap in American backing for a new order in Syria.

This past May, Obama made a cogent case for assisting the rebels. As he put it, “I made a decision that we should not put American troops into the middle of (Syria’s) increasingly sectarian war, and I believe that is the right decision. But that does not mean we shouldn’t help the Syrian people stand up against a dictator who bombs and starves his own people.”

Now that Dempsey has made it abundantly clear that the key to stopping IS in Iraq is to obliterate IS in Syria, Obama faces a major foreign policy dilemma that he cannot and should not try to evade.

Obama staunchly opposes the Assad regime. But if he launches an air offensive in Syria, with or without Assad’s approval, he will be inadvertently helping the despicable Syrian regime.

IS, having conquered wide swaths of Syrian territory in the last two years, has morphed into Assad’s most formidable adversary. But IS has also been slaughtering secular and Islamist rebels, much to Syria’s satisfaction. In the final analysis, though, Syria regards IS as its most dangerous enemy. So if U.S. aircraft smash the Syrian branch of IS, Assad and company would be one of the chief beneficiaries, an outcome that few in Washington would relish.

Yet, as Obama observed in a speech to West Point cadets three months ago, the United States has a vested interest in defeating terrorists. As he said, “For the foreseeable future, the most direct threat to America at home and abroad remains terrorism.”

IS, with as many as 17,000 motivated fighters and a deadly arsenal of captured American and Russian military equipment, certainly represents a clear and present danger to the United States and its friends and allies in the Middle East.

If IS registers more battlefield victories in Iraq and Syria, it might be emboldened to open a new front in Jordan, which has a long border with Israel. Since Israel would not allow IS to seize control of Jordan, the second Arab nation to sign a peace treaty with the Jewish state, the Middle East would be plunged into all-out war, with incalculable consequences.

IS could even send operatives to Europe and North America, and in this case, too, the repercussions could be disastrous.

IS must be crushed — the sooner the better. And once IS has been disposed of, the United States can deal with Assad.

.