On a sunny autumn day in the Negev desert 20 years ago this month, Israel signed a peace treaty with Jordan. Coming 15 years after Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, the first of its kind in the Middle East, it was seen as step forward in Israel’s quest for recognition and acceptance in the Arab world.

But since that historic moment on Oct. 26, 1994, Israel’s complex and mercurial relationship with Jordan has frayed at the edges.

Israel’s relations with Jordan, a pro-Western monarchy, have deteriorated against the backdrop of several events — the second Palestinian uprising, which lasted from 2000 to about 2005 and which prompted Jordan to temporarily recall its ambassador in Tel Aviv; Israel’s construction of a security fence along the length of the West Bank, a project that has yet to be finished; Israel’s unilateral withdrawal in 2005 from the Gaza Strip, which Jordan criticized because it left Israel still in control of the West Bank; the three wars in the Gaza Strip, which Jordan has generally blamed on Israel, and the failure of the most recent Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, which collapsed in April after nine months of fitful negotiations.

To observers who had hoped that Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan would be warmer than Israel’s cold treaty with Egypt, the disillusionment has been profound.

No one, however, should be surprised by the turn of events.

Two-thirds of Jordan’s population consists of Palestinian Arabs who were displaced by the 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars who who have yet to reconcile themselves to Israel’s existence. And the Islamic movement in Jordan is stridently anti-Israel.

King Hussein, the late Jordanian monarch who promoted the treaty in tandem with his partner, the late Yitzhak Rabin, knew that it would not enjoy widespread grassroots support, especially in Palestinian and Islamic circles. But he regarded the treaty as a strategic asset. He wished to normalize relations and resolve border disputes with Israel, bolster ties with the United States, improve Jordan’s anemic economy and take up Israel on its generous offer of channelling water to his parched kingdom.

Rightly or wrongly, King Hussein believed he could perform a delicate balancing act — maintaining reasonably good relations with Israel while preserving Jordan’s special links with the Palestinians in particular and with the Arabs in general.

King Hussein, who had met secretly over the years with virtually every Israeli prime minister from David Ben-Gurion on down, underestimated the impact the unresolved and festering Palestinian problem would have on his treaty with Israel.

Benjamin Netanyahu’s election as prime minister in 1996 was a turning point in Israel’s relations with Jordan. Netanyahu was a fierce opponent of the Olso peace process, which was launched in 1993, while Jordan supported it.

King Hussein’s attitude toward Netanyahu grew more sour in the wake of the tunnel riots in eastern Jerusalem in the summer of 1996. These disturbances, which caused the deaths of 15 Israeli soldiers and 80 Palestinians, prompted the Jordanian ambassador to Israel to warn that Jordan’s relations with Israel had worsened and could not be mended until the Israeli government changed its negative attitude toward Oslo.

Netanyahu also ruffled Jordan’s feathers in March 1997, when he announced that a massive housing estate would be constructed in Har Homa, a district in eastern Jerusalem that Israel captured and annexed during the 1967 Six Day War, when Israel was at war with Jordan. Har Homa emboldened the Palestinians to suspend bilateral talks with Israel and caused Jordan to question Israel’s commitment to peace.

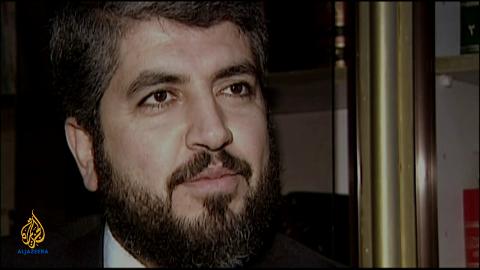

Israel’s attempted assassination of Khaled Mashaal, a Hamas leader residing in Jordan, in September of 1997 infuriated King Hussein, who temporarily suspended security cooperation with Israel. To mollify King Hussein, who had threatened to cancel the peace treaty, Israel sent an antidote to save Mashaal’s life, fired the director of the Mossad, Danny Yotam, and released from prison Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader.

But the damage was done.

Israel’s former ambassador to Jordan, Shimon Shamir, observed that “impatience, apprehension and suspicion” would now characterize Israel’s relations with Jordan. Meanwhile, Canada was upset that Mossad agents who had tailed Mashaal had used Canadian passports to enter Jordan.

The death of King Hussein in 1999 brought his untested son, Abdullah II, to the throne. Having promised to uphold his father’s rapprochement with Israel, he visited Israel and upgraded economic relations with the Jewish state by creating more joint venture industrial zones, which have boosted Jordanian exports to the United States in particular.

And in accordance with King Abdullah’s pledge to maintain ties with Israel, the Jordanian prime minister, Ali Abu al-Ragheb, criticized professional associations and unions in Jordan opposed to normalization with Israel. Claiming they were harming Jordan’s interests, Ragheb said that Jordan would “protect all whose who establish ties with Israel.”

To this day, nevertheless, many Jordanians still boycott Israel and regard the peace treaty as a curse, referring to it as “the king’s peace.”

Last February, 86 out of 150 members of Jordan’s parliament voted in favor of a motion to expel Israel’s ambassador in Amman. And this past September, a senior member of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood, Himam Said, urged the government to sever diplomatic relations with Israel. King Abdullah ignored these calls.

Jordanians who oppose Jordan’s relationship with Israel have resorted to violence at times. In 1997 and 1999, gunmen opened fire on the closely guarded Israeli embassy in Amman. And in 1999 and 2000, Israeli diplomats had to dodge bullets while driving to work. In 1997, a Jordanian soldier killed seven Israeli school children in a border area near the town of Beit Shean. King Hussein, in an extraordinary gesture, flew to Israel to offer his condolences to the bereaved families.

Cross-border infiltrations have also been a problem, despite the fact that the Arab Legion — the Jordanian army — watches the frontier carefully. In one of the most serious incidents, in December 2001, an Israeli soldier was killed in an ambush.

To a great extent, Jordan’s relationship with Israel is bound up with the Palestinians. As Marwan Muasher, Jordan’s first ambassador to Israel, once said, “Our ties with Israel will be largely dependent, from a political point of view, on the commitment of Israel’s government to the peace process with the Palestinians. If the Israeli government is serious, the ties between the two countries will improve greatly.”

Since then, King Abdullah has repeatedly called on Israel to be more flexible and accommodating in its approach to peaceful relations with the Palestinians. Jordan’s formal position is that Israel should withdraw to the pre-1967 armistice lines so that a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip can be established.

The abysmal lack of progress in peacemaking, however, has not prevented Jordan from deepening its bonds with Israel.

Last year, King Abdullah described his personal relations with Netanyahu as “very strong.” And two months ago, Israel signed a memorandum of understanding with Jordan under which it will supply the Jordanians with $15 billion worth of natural gas over 15 years.

Israel’s minister of water and energy, Silvan Shalom, hailed the accord as “a historic act that will strengthen the economic and diplomatic ties between Israel and Jordan.”

Despite the bumps along the way, Israel regards its relations with Jordan with the utmost importance and constantly cultivates them. Recently, Channel 2, an Israeli TV station, reported that Israel would not hesitate to act forcefully should Islamic State — the jihadist organization that has wreaked havoc in Iraq and Syria of late — invade Jordan.

Jordan is that crucial to Israel’s strategic interests. And vice-versa.

This piece appeared in The Times of Israel on Oct. 23, 2014.