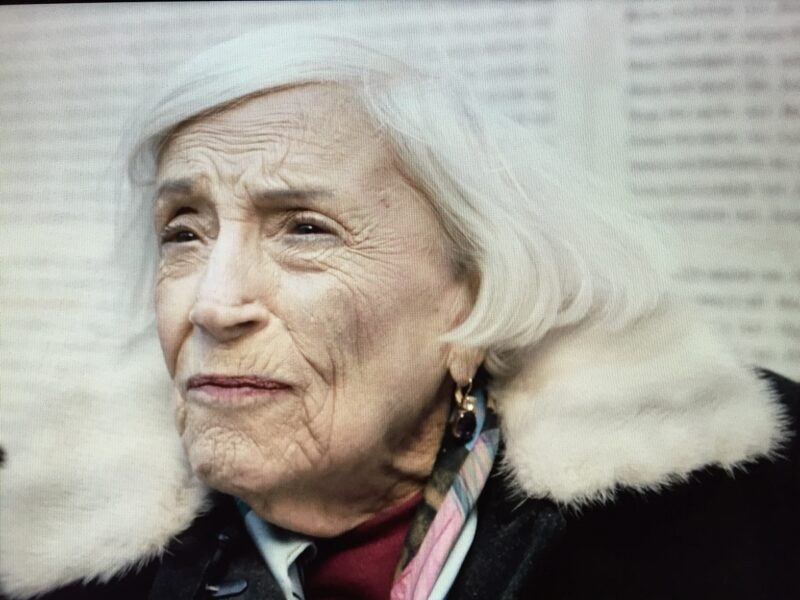

Marthe Hofnung Cohn is quite a lady.

During the final weeks of World War II, this French Jewish woman was spy in Nazi Germany, providing France with vital, real-time intelligence about the movement of German army troops. Cohn’s exploits, the stuff of legend, were known only to a select few in 1945, when she courageously sneaked into Germany through neutral Switzerland.

Nicola Alice Hens’ documentary, Chichinette: How I Accidentally Became A Spy, fills in the blanks. It will be screened online on June 4 by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival.

Unprepossessing in appearance but irrepressibly lively and charming, Cohn lives in Los Angeles today with her husband, Major, a physician. They travel the world together as she delivers speeches about this intriguing facet of her life. Hens’ film documents her travels and her brief foray into espionage.

Born in 1920 in Metz, Cohn grew up speaking French and German. When Germany occupied France in 1940, she was forced to wear the degrading yellow Star of David. Thanks to a friend’s warning of an imminent German roundup of Jews, she escaped. Having obtained a “fake passport,” she could identify herself as a Christian and move around freely.

Judging by old photographs, she could easily pass as a non-Jew. Finding refuge in Marseille, in the French “free zone,” Cohn studied nursing. Then she found an internship in Paris.

Cohn’s younger sister, Stephane, was not as lucky. Arrested by the Germans, she was deported to a Nazi extermination camp in Poland. Cohn’s parents and second sister managed to survive, but details are lacking.

Following the liberation of Paris in August 1944, Cohn joined the French army as a nurse. Parts of France were still occupied by the Germans at this point. By sheer accident, she was transferred to the intelligence service, which required fluent German speakers.

About a month before Germany’s surrender, Cohn clandestinely crossed into Germany under the name of Martha Ulrich. Establishing herself in the Black Forest city of Freiburg, she gathered intelligence regarding the morale of its inhabitants. Hens glosses over this aspect of Cohn’s mission, except for a passing reference to anti-Nazi farmers who assisted her.

Cohn made her most important contributions by providing her handlers with vital information about Germany’s defensive Siegfried Line and the disposition of its soldiers in the Black Forest. This enabled the French army to bypass German troop concentrations and thereby avoid a direct clash with the Wehrmacht, which might have been costly in terms of casualties.

Cohn’s stellar performance earned her a pocketful of medals, including the coveted Croix de Guerre. At her lectures today, she proudly displays these medals.

After the war, Cohn worked in Vietnam. Hens spends precious little time on this interregnum, or on her move to Los Angeles after meeting her husband. Cohn was his assistant for some 40 years and following his retirement, they switched roles. It would appear that he enjoys travelling with her in the United States and Europe.

She has a very interesting story to tell and Chichinette, a co-French and German production, imparts it with panache.