During his confirmation hearing in the U.S. Senate two and a half years ago, President Donald Trump’s nominee for the post of ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, vowed to refrain from making partisan comments while on duty.

“Partisan rhetoric is rarely, if ever, appropriate for achieving diplomatic progress, especially in a sensitive and strife-torn region like the Middle East,” said Friedman, who had come under fire after labelling leaders of the dovish pro-Israel lobby J Street as “kapos.”

“If I am confirmed, you should expect that my comments will be respectful and measured,” he added.

Friedman, who has described himself as “an unapologetic right-wing defender of Israel,” has not lived up to his promise.

Since assuming his position at the U.S. embassy in Israel in 2017, he has gladdened hearts in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, probably the most right-wing one in Israeli history, and enraged the leadership of the Palestinian Authority.

Friedman hardly behaves like an impartial diplomat.

In right-wing Israeli circles, Friedman — an Orthodox Jew who was a major donor to Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Trump’s bankruptcy lawyer — is admired as a principled and outspoken diplomat with a nuanced understanding of Israel, the Arab-Israeli conflict and American interests in the Middle East. As a result, he has formed a close working relationship with Netanyahu, with whom he confers quite frequently, and is regarded as something of a hero among Jewish settlers.

The Palestinians have an entirely different view of Friedman. “I can’t believe this extreme fundamentalist ideologue is an ambassador,” Hanan Ashrawi, a leading Palestinian spokesperson, said recently.

Daniel Kurtzer, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel, is critical as well, having called Friedman “the ambassador of the far-right Orthodox Jewish community in the United States.”

In fact, Friedman speaks for his boss, who is proving to be the most pro-Israel president since Israel’s founding in 1948. In short, Friedman is his master’s voice in Israel, a diplomat who has been given a lot of leeway to speak his mind.

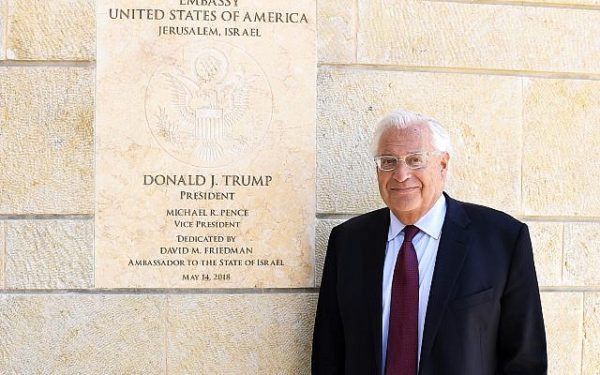

Netanyahu is extremely satisfied with Trump. Fulfilling his fondest wishes, Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, moved the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and recognized Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights. Much to Israel’s satisfaction, he also closed the Palestine Liberation Organization office in Washington, D.C. and cut off funding to the United Nations Agency that provides economic relief to Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

Although Trump claims he supports a two-state solution, he has remained silent in the face of comments by Netanyahu rejecting Palestinian statehood and announcements by Israel expanding its network of settlements in the West Bank. No U.S. president since the Six Day War has been as accepting of the settlement project as Trump.

Trump has made it clear he wants to resolve Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians in the “deal of the century.” For the past year, his administration has been working on a peace plan. Yet the two most important members of his Middle East team, Jared Kushner — his son-in-law and senior advisor — and Jason Greenblatt — his in-house lawyer at the Trump Organization and now his special envoy to the Middle East — have both deliberately shied away from using the expression “two-state solution.”

Friedman, who confers regularly with Kushner and Greenblatt, said he has difficulty with the term because it means “so many different things to so many different people.”

Contrary to the promise he made to U.S. senators in 2017, Friedman has engaged in sharp pro-Israel partisanship in his speeches, much to the outrage and disappointment of the Palestinians.

Most recently, he declared that Israel, “under certain circumstances,” is “entitled to retain some portion” of the West Bank. Subsequently, Greenblatt expressed support for his position. Friedman and Greenblatt were taking their cue from Netanyahu, who, during the last general election campaign in Israel, pledged to annex Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Friedman’s comment was hardly surprising, given his propensity to support hard-line Israeli positions.

Last March, he proclaimed that the Trump administration will not force Israel to relinquish parts of the West Bank that it requires for its security. In 2017, he lobbied the U.S. State Department to stop using the word “occupation” when referring to Israel’s presence ion the West Bank.

Last month, in a highly partisan remark, Friedman claimed that “Israel is on the side of God.” It was a comment bound to appeal to Christian fundamentalists and Orthodox Jews, who form part of Trump’s base.

Nine months ago, he said, “Where Palestinian autonomy and Israeli security intersect, we err on the side of Israeli security. It’s a very different view than I think has been expressed in the past.”

Six months before Trump officially endorsed Israel’s 1981 annexation of the Golan, Friedman said, “I cannot honestly imagine a situation in which the Golan is not part of Israeli forever. I cannot imagine a situation in which the Golan is returned to Syria.”

Clearly, Friedman is a hardliner on Arab-Israeli issues whose views blend in with those of Trump. And he has no intention of playing the role of a traditional diplomat.