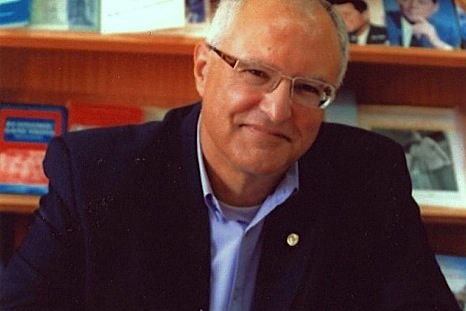

Mohammed Dajani, a professor at Al Quds University in eastern Jerusalem, is the kind of Palestinian the Palestinians need more of. Once a flaming radical, he’s now a pragmatist who supports a two-state solution to defuse the Arab-Israeli conflict and espouses such eternal and precious values as reconciliation and dialogue.

Driven by these laudable ideas, Dajani recently brought 27 of his students to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the former Nazi extermination camp in Poland, for a visit as part of a project to teach tolerance and empathy.

By all accounts, the trip was a success. But upon their return, all hell broke loose. Some Palestinians branded him him a traitor to the Palestinian cause, while Al Quds disowned Dajani and the participants, saying they did not represent the university.

Still other Palestinians were upset that Jewish organizations had supposedly financed the visit, when, in fact, it was paid for by the German Research Foundation and organized by the Center for Reconciliation Studies at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena.

To Jews, the Holocaust is a profoundly tragic and incomprehensible event that resulted in the needless deaths of six million European Jews.

To the vast majority of Palestinians, however, the Holocaust is something else completely. It’s a tragedy that Israel’s founding fathers used to elicit sympathy for Jewish statehood, which uprooted and displaced several hundred thousand Palestinians from their homes in Palestine. It’s also, they believe, a line of argumentation that Israel raises to justify policies they find utterly objectionable.

Certainly, whether sincerely or cynically, Israeli leaders have evoked the Holocaust in defence of this or that policy. Menachem Begin raised it after Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982.Benjamin Netanyahu, his ideological successor, has mentioned it in speeches pertaining to Iran’s controversial nuclear program.

The Holocaust has been woven into the fabric of Israel’s historical narrative. It’s incorporated into Israeli school texts, and when foreign heads of state come to Israel on official visits, they are taken to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial and museum in western Jerusalem.

Most Palestinians, while perhaps expressing a measure of sympathy for the Jewish victims of Nazism, tend to view the Holocaust through the prism of the nakba, the catastrophe that rendered many of them homeless in the wake of the 1948 war. They regard the Holocaust as a propaganda tool at Israel’s disposal. Yet other Palestinians downplay the centrality of the Holocaust or, if they’re members of Hamas, engage in Holocaust denial.

Dajani, a keen observer of the Palestinian community, was acutely aware of these currents when he organized the educational trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau. By the same token, he understood that true reconciliation and fruitful dialogue between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs can only begin in earnest after both sides gain at least a rudimentary understanding and appreciation of each other’s fears, traumas and hopes.

Yet when Dajani and the students returned from Poland, they were met by a wave of condemnation, with critics claiming they had committed a form of treason.

It’s disappointing that their trip was greeted with such negativity. Real peace, if it is even possible, will remain elusive as long as Palestinians respond to the Holocaust so bitterly. Their short-sighted attitude will only harden Jewish hearts and make it all the harder to resolve contentious issues, from final borders to Palestinian refugees, that continue to block progress toward an equitable peace agreement.

Courageous and visionary Palestinians like Dajani should be commended for their commitment to peace and peaceful relations. Without Palestinians like him, the struggle pitting Israeli Jews against Palestinian Arabs will consume many more lives.

In this context, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas should be commended for having described the Holocaust as “the most heinous crime to have occurred against humanity in the modern era.”

Correctly, Yad Vashem said his comment “might signal a change in the way the subject is treated in the Arab world and among the Palestinian public.”

One can only hope so.