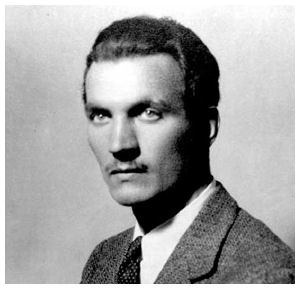

Jan Karski, born a century ago this month, was a member of the Polish resistance movement during World War II and wrote a searing expose of Nazi crimes in German-occupied Poland.

Published in the United States in 1944, when the Jewish community in Poland had already been virtually decimated, Courier from Poland: The Story of a Secret State was a bestseller, with 400,000 copies having been sold.

Two years ago, Penguin Classics reprinted this important book under a new title, Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World. A raw, blistering account of a nation under brutal occupation and unimaginable duress, Karski’s book was a bombshell, alerting Americans to the Holocaust.

At the behest of the Polish government-in-exile in London, Karski, a former diplomat born in Lodz in 1914, twice visited the Warsaw Ghetto and had himself smuggled into the Izbica Lubelska transit camp, an annex of the Belzec concentration camp.

These visits shocked him to the core of his soul and turned him an invaluable witness to unprecedented crimes against humanity.

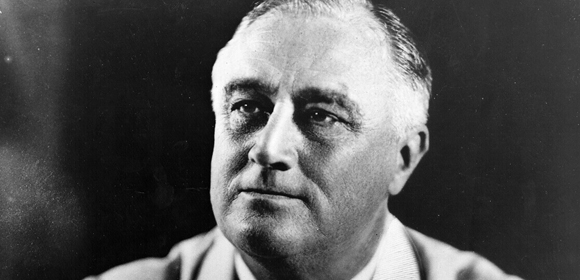

On trips to Britain and the United States, where he met U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, among others, Karski relayed this chilling information to the Allies. Karski urged them to bomb the rail lines leading to Auschwitz, but they chose to ignore his advice, despite having bombed German facilities nearby.

After the war, Karski settled in the United States, became a naturalized citizen and began a 40-year career as a professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. After he retired in the mid-1980s, a memorial statue of him sitting on a bench was erected on the campus.

Last week, on the anniversary of his birth, the university honored him in a series of special events.

The French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann plucked him out of obscurity in 1985 by including him in his epic documentary, Shoah.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, recognized him as a Righteous Gentile in 1982. Twelve years later, Israel conferred honorary citizenship on Karski, who died in 2000. After the fall of communism in Poland in 1989, his role was officially acknowledged.

Karski, whose real name was Jan Kozielewski, was called up by the Polish armed forces upon the outbreak of war in 1939. With Poland having been partitioned by Germany and the Soviet Union after their separate but coordinated invasions, Karski joined what would be the Polish Home Army after escaping from Soviet captivity.

Highly intelligent and possessing a photographic memory, he repeatedly crossed enemy lines as a courier. On one such mission, he was caught by the Gestapo and tortured.

Story of a Secret State is, in essence, a cri de coeur.

“The world I lived in was falling apart around me,” he writes of the period following Poland’s catastrophic defeat. “I felt like a shipwrecked man in the ocean…” After visiting Poland’s capital, he observes: “Warsaw was a shocking ruin of its former self.”

Although he remains convinced that Poland will be liberated from the Nazi yoke, he is gloomy: “Everywhere about me I saw chaos, ruins, despair and indescribable poverty. German arrogance and German terror affected everyone…”

Karski’s Gestapo interrogator is a brute. As he informs Karski, “I assure you, after a few of our caresses, you will regard death as a luxury.”

A Gestapo agent who vainly tries to turn him into a collaborator says, “We do not want to harm anyone. With the exception of the Jews, of course. They will be exterminated. This is the Fuhrer’s will.”

Disgusted by Nazi massacres of civilians, he notes, “This incredible baseness on the part of Germany will never be forgotten or forgiven.”

Expressing defiance, Karski says, “We fought back by every conceivable means in a naked struggle to survive against an enemy determined to destroy us.”

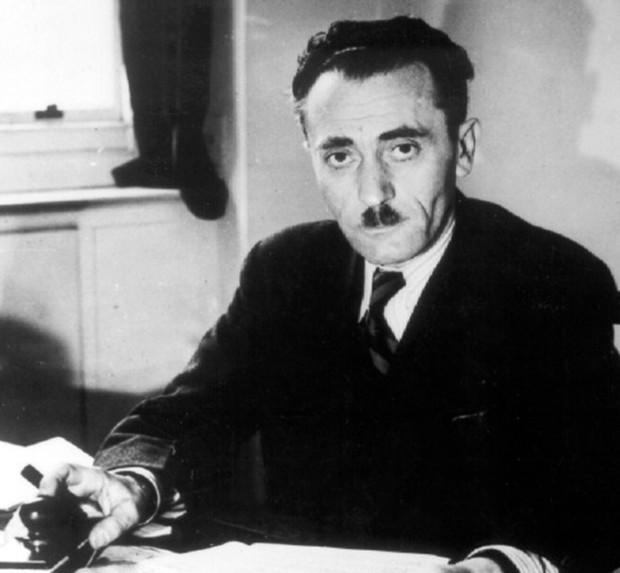

In 1942, when Polish Jews are being murdered ruthlessly in town after town, he meets two Jewish leaders in a Warsaw suburb. They are Leon Feiner of the Bund and a Zionist representative whose identity is still unknown.

Their revelations shake him: “Never in the history of mankind… did anything occur to compare what was inflicted on the Jewish population of Poland.”

And in great pain, he adds, “The first thing that became clear to me as I sat there talking to them … was the complete hopelessness of their predicament. For them, for the suffering of Polish Jews, this was the end if the world.”

Two days later, accompanied by the Bund leader and a Jewish guide, and wearing an old, shabby suit and a cap pulled down over his eyes, Karski ventured into the ghetto.

- The Warsaw ghetto

His observations are stinging: “Everywhere there was hunger, misery, the atrocious stench of decomposing bodies, the pitiful moans of dying children, the desperate cries and gasps of a people struggling for life against impossible odds.”

In horror, he watches two boys, dressed in the uniform of the Hitlerjugend, shooting a man for the sport of it.

Returning to the ghetto to memorize his visual impressions, Karski subsequently reports his experiences to British and U.S. government officials and Jewish leaders. In London, he meets Szmul Zygelbojm, a Bund leader who, in utter despair, committed suicide.

“Of all the deaths that have taken place in this war,” he writes with passion, “surely Zygelbojm’s is one of the most frightening, the sharpest revelation of the extent to which the world has become cold and unfriendly, nations and individuals separated by immense gulfs of indifference, selfishness and convenience.”

Karski’s clandestine inspection of Izbica Lubelska — a way station to Belzec — is horrifying, or, as he puts it, “a ghastly ordeal.”

His guide there, a Ukrainian guard whom he mistook for an Estonian, told him of his interest in saving Jewish inmates. Karski asked him, “Are there many more good men like you there who are willing to save the Jews?” The guard replied, “Save them? Say, who wants to save them?” The guard looked at Karski in bewilderment, as if he was a fool. “But if they pay, that’s a different story. We can all use some money.”

Walking through the desolate camp, Karski is appalled by the sight of its imprisoned Jewish inhabitants, who were rounded up in the Warsaw Ghetto. “The Jewish masses vibrated, trembled and moved to and fro as if united in a single, insane, rhythmic trance … They had become … completely dehumanized … The chaos, the squalor, the hideousness … was … indescribable.”

He is particularly repelled by the guards’ practice of squeezing more than 120 Jews into freight cars that can normally accommodate 40 soldiers and eight horses and of lining the cars with quick lime that burn them to death before too long.

After exiting the camp, he is seized by a violent fit of nausea and vomits for the next two days.

In the final pages of this strong and affecting book, Karski describes his meetings with Allied and Jewish leaders and leaves a reader with the indelible impression that he was a man of resolve, courage and vision.

One hundred years after his birth, the verdict on Karski is that he was a mensch.