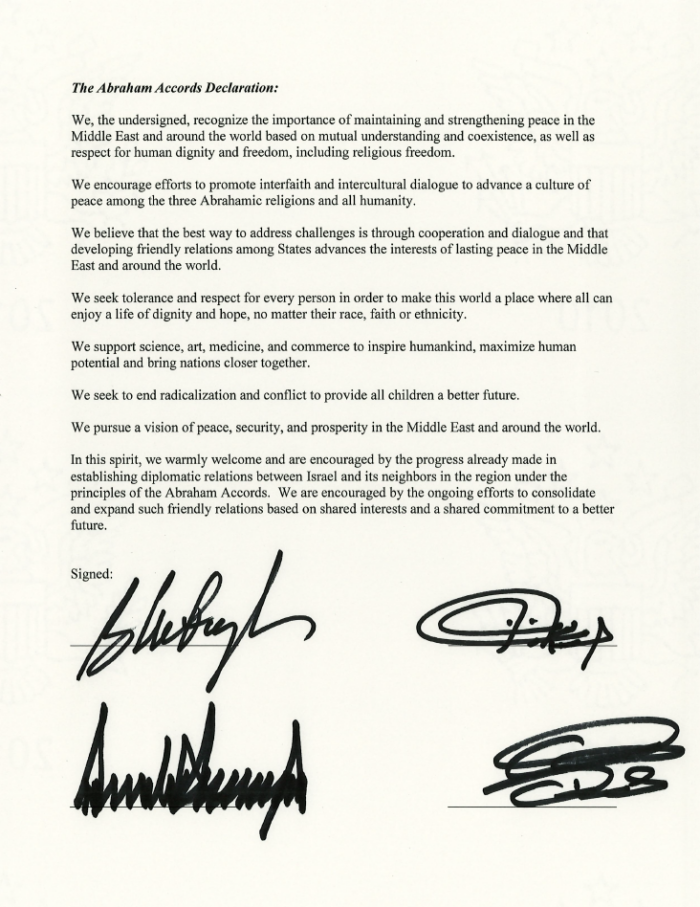

The White House ceremony on September 15 at which Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates formalized their normalization agreements could well herald the dawn of a new era in the Middle East, as President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu both declared in separate speeches.

Counting its 1979 and 1994 treaties with Egypt and Jordan, Israel has now signed peace accords with four Sunni Arab countries. This may be a significant development should more Sunni states, such as Saudi Arabia, Oman or Morocco, establish diplomatic relations Israel and thereby form a de facto alliance against a common foe — Iran, the preeminent Shi’a power in the region and Israel’s arch enemy.

In this vein, Trump disclosed that five to six additional Arab countries may “very, very soon” follow the example set by the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

Lauding Israel’s agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, the culmination of years of secret diplomacy and changing regional realities, Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz joked that Israel should thank Iran for this historic breakthrough.

The Islamic fundamentalist Iranian regime has implicitly or explicitly threatened all three nations, which regard Iran as a menace to their security.

These accords are historically important because they signify a sea change in Arab attitudes toward Israel and its protracted conflict with the Palestinians. It was once a given that Arab governments would not sign a peace treaty with Israel unless the Palestinian issue was completely resolved. Arab states still regard it with the utmost importance, but, in a stunning departure from the past, are now politically and psychologically prepared to bypass the Palestinians if it serves their vital national interests.

Yossi Cohen, the head of the Mossad intelligence agency, said that the agreements signified “the breaking of a glass ceiling that existed in our relations with Arab states.”

Certain Arab states, such as Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, still hew to a conventional approach to Israel, perceiving it as an artificial entity and a colonial settler state that has no right to exist in light of the dispossession of the Palestinians after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Islamic groups, ranging from Hezbollah and Hamas to Al Qaeda and Islamic State, are ideologically opposed to Israel’s existence and locked in obduracy.

But conservative Arab monarchies, which are allied with the United States and which have never engaged Israel in a war, are ready to consider the idea that Israel is a legitimate state and that Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians should not block a pragmatic, mutually beneficial accommodation.

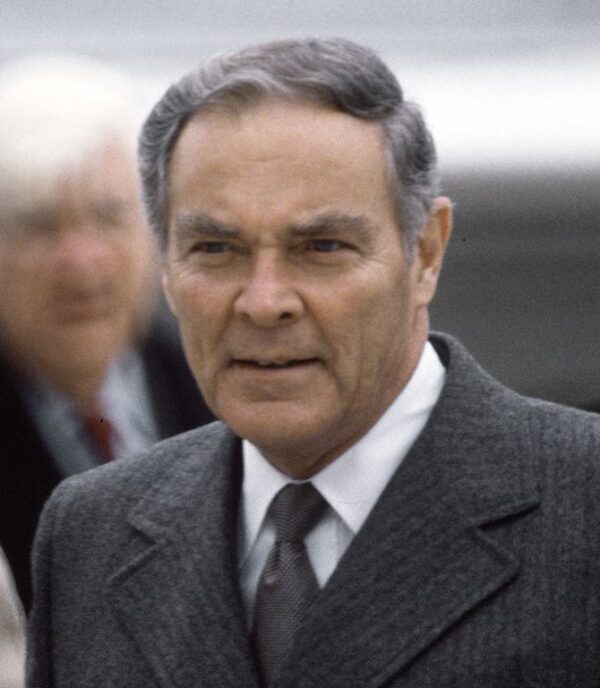

Forty years ago, the then U.S. Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, enunciated a doctrine turning on the thesis that shared political interests, or a “strategic consensus,” could embolden at least some Arab leaders to forge peace with Israel.

The concept appealed to the Israeli government of the day, led by Prime Minister Menahem Begin, yet Arab regimes close to the United States were not interested. They were deeply invested in the Palestinian cause and had so demonized Israel on a grassroots level that it might be too risky to agree to an Egyptian-style rapprochement with Israel.

Breaking with the Arab world in spectacular fashion, Egypt’s president, Anwar Sadat, visited Israel in 1977 in a bid to create a new status quo in the region. His whirlwind trip to Jerusalem kick started bilateral negotiations, which led to Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt and its withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. But in 1981, Islamic radicals assassinated Sadat, citing his Egypt-first policy and recognition of Israel.

Only a year later, as Israel entrenched itself in southern Lebanon following its invasion, Lebanon’s newly-installed Maronite Christian president, Bashir Gemayel, hinted he would sign a peace treaty with Israel. Shortly afterward, he was assassinated.

These twin assassinations gave Arab leaders pause regarding the possibility of a modus vivendi with Israel. But after the 1993 Oslo accord, which held out the prospect of Palestinian self-determination in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Jordan signed a peace treaty with Israel, while Morocco and Persian Gulf nations like Oman and Qatar created lines of communication with the so-called Zionist enemy.

After nearly 30 years of overt and covert relations with Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, two of the most pro-American countries in the Middle East, finally took the plunge and recognized Israel.

But in doing so, they needed a fig leaf to justify their dramatic volte face, which enraged the Palestinians.

On the eve of the ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House, the United Arab Emirates’ minister of state for foreign affairs, Anwar Gargash, said his country remains committed to a “viable, independent” Palestinian state, with East Jerusalem as its capital. He also said his nation still supports the 2002 Arab League peace proposal and its revised 2007 version, which broadly calls for a full Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories in exchange for normalization with all its member states.

Bahrain’s foreign minister, Abdul Latif bin Rashad al-Zayani, conveyed the same point: “Bahrain always stresses its firm and constant position toward the right of the fraternal Palestinian people, which is at the top of its priorities.”

Judging by the documents, the normalization agreements between Israel and its newest Arab partners barely mention the Palestinians, apart from a routine call for a “just, comprehensive, realistic and enduring resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

In comments at the ceremony, Al-Zayani said that a two-state solution will anchor regional peace. His Emirati counterpart, Abdullah bin Zayed a-Nahyan, spoke favorably of Israel’s decision to suspend the annexation of “the Palestinian territories” in the West Bank.

The Palestinians, of course, were not impressed by these conciliatory gestures.

Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, warned that peace, security and stability will not be achieved unless Israel’s occupation of the West Bank ends and the Palestinians attain their “full rights.”

Hamas, which governs Gaza, dismissed the normalization agreements as worthless. A Hamas spokesman said, “Our people insists on continuing its struggle until it secures the return of all its rights.”

As the ceremony in Washington unfolded, Palestinians made a symbolic show of their displeasure. Two rockets fired from Gaza struck the Israeli cities of Ashkelon and Ashdod, injuring two civilians and causing minor damage. In retaliatory raids, Israeli aircraft bombed military sites in Gaza. Subsequently, the Palestinians launched 11 more rockets into Israel.

So despite the understandable fanfare hailing the normalization accords, Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians burns as brightly as ever.

In an allusion to this deficit, Benny Gantz called for a renewal of talks with the Palestinians. “It is also important to make peace with our neighbors,” he said in a grand understatement that speaks to the Israeli government’s complacency with respect to resolving the Palestinian imbroglio.