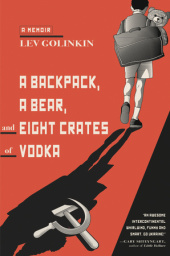

Lev Golinkin’s bracing memoir of boyhood in the Soviet Union and manhood in the United States, A Backpack, A Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka (Doubleday), bears a striking resemblance to Gary Shtenyngart’s Little Failure, which I read last year.

Like so many Soviet Jews born in the Soviet Union, the two authors share common experiences. They were made to feel like rank outsiders. They were subjected to antisemitic jibes. They were only to glad to leave. They were grateful to be reborn in the United States.

Golinkin was born in Kharkov, where four major battles of World War II took place and which still bore its scars when he was growing up in the 1980s, the twilight of the Soviet Union. “Our balcony wall was pockmarked with mortar holes,” he writes. “Memorial plaques and captured panzer war trophies littered the city.”

During the war, Golinkin’s family was evacuated to the Urals and thus spared the brunt of Nazi brutality. But 15,000 Jews who remained behind were killed in a ravine on the outskirts of Kharkov, now part of Ukraine.

Despite the Nazi legacy of genocide, postwar Soviet regimes marginalized Jews. Golinkin was taunted and beaten by antisemitic school mates. His sister, Lina, a straight-A student, was barred from medical school simply because she was Jewish. Their father, an engineer, was to have presented a paper on turbines in Bulgaria, but was replaced at the last minute by a non-Jew.

Golinkin’s grandparents, who came of age before the pre-1917 Bolshevik period, experienced a more primitive form of antisemitism. As he puts it, “Antisemitism in my grandparents’ time manifested itself in pogroms (which) shattered and burned, raped and looted … Long centuries taught Jews to view them as seasonal calamities, unavoidable evils like famine and drought.”

In accordance with Soviet atheistic practice, Jews were cut off from their traditions. Golinkin’s grandfather spoke Yiddish and was intimately connected to his history and customs, but his son — Golinkin’s father — did not have access to all that.

What he inherited, he observes, was “a yearning for something his father had once had. It was a blurry vision, but it was enough to draw him down the alleyway with a sack of money and flour, risking himself for an obscure holiday that he didn’t comprehend.”

He’s referring, of course, to Passover.

“Purchasing matzah in Kharkov required money, flour and discretion,” he writes. “The money went to the underground bakers who operated out of apartments throughout the city. But even with the reforms that had begun to creep into Soviet society, it was still dangerous for bakers to purchase large quantities of flower in the springtime.”

Such bakers, he notes, could face imprisonment.

Due to the repressive atmosphere, Golinkin’s mother, a psychiatrist, decided that the Soviet Union was no longer a fit country to bring up a Jewish child. She made that decision impulsively after Golinkin returned from school one day with a bruise over his eye, the result of yet another beating.

“We, Russian Jews, were persecuted not because of our religion but because of our ethnicity,” he says. “We had no religion, spoke no prayers, and, aside from a few old superstitions and vestigial snippets of Yiddish, had little religious tradition.”

Antisemitism had bred an element of self-hatred in Jews like Golinkin. “The only prayer I ever had was a vague desperate wish to not be myself and shed the horrible, unalterable ethnic zhid features I spied in the mirror,” he acknowledges.

“What my family and many families like mine desired was peace of mind, not a synagogue,” he adds. “We wanted freedom, the freedom to live our lives without trembling, and naturally we, like our innumerable predecessors, cast our gaze across the Atlantic. Israel may be a Western nation, but, as the Russian Jews who did immigrate there found out, it’s also flavoured with a bit of theocracy — if not governmental, then certainly cultural.”

Elaborating on this theme, Golinkin says, “A Russian couldn’t imagine kicking ham off the menu … We wanted ham, we craved ham, we wanted to live in a land where bacon flowed like wine, a land brimming with pork chops served in stores open on the Sabbath, and we didn’t want anyone wagging their finger and informing us we were sinning. We’d paid our dues to our ethnicity; the Soviet Union had made sure of that.”

Apart from these reasons, the Golinkins bypassed Israel because they were averse to Israel’s climate, had already begun learning English and had a friend in America who could supposedly land them jobs.

Finally, in 1989, the Golinkins emigrated. But as they lined up at the customs counter to declare their goods, Golinkin’s father perspired profusely. “I didn’t know it at the time, and I wouldn’t find out for quite a while, but dad had a very good reason to sweat. Under his long brown coat, beneath the layers of sweaters and the undershirt, nestled deep within his underwear, were eleven tiny metal disks, microfilms containing engineering patents, designs and sketches of future ideas — three decades of dad’s work.”

Fearing he would be caught and arrested by the guards, Golinkin’s father panicked, throwing the disks into a fire blazing in a steel drum outside the building. “Pop! Pop! Pop! crackled the films, pop! pop! pop! went thirty years of painstaking labor for the very regime that had oppressed him. Pop! pop! pop! flashed dad’s chances of working again as an engineer.”

En route to the United States, the Golinkins lived temporarily in Vienna, amazed by its wealth. “We saw bright decorations, shoppers with bags, and window displays brimming with everything. To people accustomed to waiting in lines and trying to predict which common staples would be next to vanish from the shelves, this was another planet, a cornucopia, albeit with a hefty price tag.”

He and his parents settled in West Lafayette, Indiana, and then in New Jersey, where they began the long process of acculturating themselves to a new home and culture. It was difficult. Golinkin’s father initially worked as a file clerk, his mother as a security guard. “Mom and dad were thrashing about, grasping to regain their dignity. Their situation made them feel powerless and humiliated.”

Yet the Golinkins had achieved something of value by having left the Soviet Union. “Mom and dad made it clear that Lina and I were the main reason they had decided to risk it all and flee the USSR. Their children were going to have a better future.”

Within several years of immigrating to the United States, he says, they had “abandoned all pretenses of being religiously and culturally Jewish.” Jewish observances remained alien to them, while major Jewish holidays were merely convenient days off.

“The ultimate irony of the experience of Soviet Jews in America is that the people who fled to the States in search of cultural freedom adopted irreligious, secular lives, eschewing community and synagogue alike. The vast majority of ex-Soviet Jews did not, to put it bluntly, want to be Jewish.”

Which is why Golinkin chose to pursue his university studies at Boston College, a Jesuit institution. “Little did I suspect that from Boston College I, who had enrolled as an antisemite, would emerge a Jew.”

I presume that’s the theme of Golinkin’s next book, to which I look forward.