When President George W. Bush launched Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, roughly a month after more than a dozen airborne Al-Qaeda Arab terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., he warned Americans to expect “a lengthy campaign unlike any other we have ever seen.”

Little did he know that the United States had launched what would be its longest war — a protracted conflict that has preoccupied four U.S. presidents, claimed the lives of 2,400 American troops and cost billions of dollars annually.

On April 14, President Joe Biden finally pulled the plug on what he aptly described as “the forever war,” issuing a timetable during which the U.S. garrison in Afghanistan will be withdrawn incrementally.

The pullout of 2,500 to 3,500 soldiers will start on May 1 and finish on September 11, the 20th anniversary of 9/11. A token American force will be left behind to guard the U.S. embassy, collect intelligence, and train and provide support for the Afghan army, which has been fighting a losing battle against the Taliban.

An additional 7,000 troops from NATO nations will be withdrawn as well.

The imminent departure of foreign forces from Afghanistan — a nation of rugged terrain which has been engulfed in strife for decades — comes as no surprise.

Over the past two centuries, Afghanistan has been a graveyard of empires. During the 19th century, Britain launched ill-fated incursions into this harsh land. In 1979, when the Cold War was at its height, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and stayed for a decade, its forces battered by Afghan mujahideen supplied by the United States and conservative Arab states.

In his 16-minute announcement, Biden claimed the U.S. had accomplished its overriding mission. Neither declaring victory nor admitting defeat, he said that Al-Qaeda had been defeated and that Afghanistan would never again be a safe haven from which terrorists could attack the United States.

“We were attacked,” he said. “We went to war with clear goals. We achieved these objectives. Since then, our reasons for remaining in Afghanistan have become increasingly unclear.” The U.S. undertaking in Afghanistan, he noted, was never meant to be “a multi-generational undertaking.”

“We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for withdrawal, and expecting a different result,” he he went on to say, succinctly summing up the rationale of his decision.

When Bush went to war in Afghanistan, he had two objectives in mind: to destroy Al-Qaeda’s base, where the 9/11 terrorists had trained, and to unseat the Islamic fundamentalist Taliban government, which had tolerated its activities.

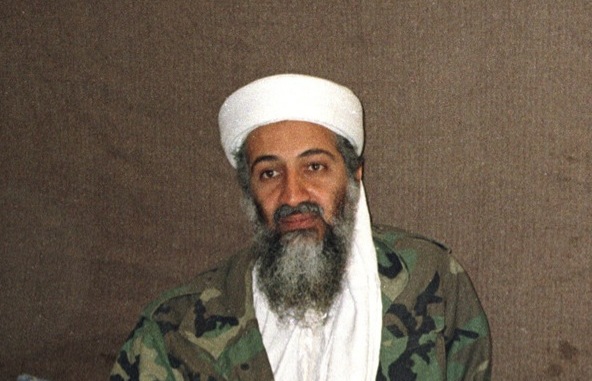

At first, the war went well for the United States. The Taliban regime, which had seized power in 1996, was toppled. The Al-Qaeda leadership, led by by Saudi Arabian national Osama bin Laden, was driven into neighboring Pakistan, a nominal American ally.

U.S. Secretary of Defence Ronald Rumsfeld announced an end to major combat operations in May 2003, a month after the United States invaded and occupied Iraq.

With the Taliban having been routed, the United States enlarged its mission. It would rebuild Afghanistan and transform it into something of a Jeffersonian democracy. In short order, a pliable pro-Western government, led by Hamid Karzai, was installed, and public works programs were set up to build schools, hospitals, roads and bridges.

One of Washington’s notable achievements was the introduction of gender equality. The Taliban had forbidden girls to be educated, but now they could finish high school, attend university and join the work force. Whether these gains can be sustained once the Americans are gone is questionable.

Despite these evident signs of progress, corruption remained endemic, with international aid dollars being misappropriated or stolen, and the lucrative drug trade continued to flourish.

The Taliban, in the meantime, rose from the ashes, rebuilding its combat capabilities to such a degree that it emerged as a major threat yet again. Fearing that a Taliban resurgence could upset the balance of power and erase all its achievements, President Barack Obama deployed yet more U.S. troops to Afghanistan, their number reaching almost 100,000 by 2010.

In the following year, U.S. commandos killed Osama bin Laden at his compound in Pakistan, dealing a crushing blow to Al-Qaeda. With the war still stalemated, Obama announced that U.S. troops would be gradually withdrawn and that Afghan forces would be in charge of security. On Dec. 31, 2014, Obama declared an end to major U.S. combat operations and turned over the prosecution of the war to the Afghan government.

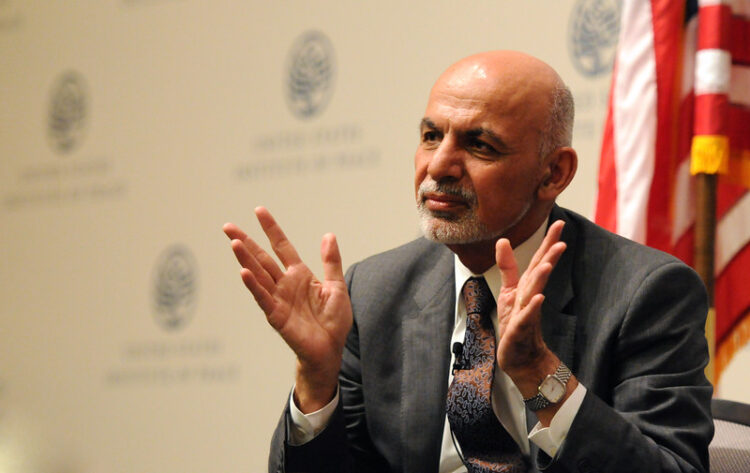

Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, signed an agreement with the Taliban in 2020 laying the groundwork for a new government and constitution and a lasting ceasefire. Under the deal, U.S. forces would leave by May 1, 2021 and the Taliban would reduce its military operations, negotiate with the U.S.-backed Afghan government of President Mohammed Ashraf Ghani, and sever ties with Al- Qaeda and the Islamic State organization, which has carried out suicide bombings throughout Afghanistan.

For a while, the truce held, but of late it has begun to crumble. In the past few months, more than 1,700 civilians have been killed or wounded in attacks for which no one has claimed credit. It would appear that Afghanistan is sinking into anarchy again.

There are fears that Afghanistan will be overwhelmed by worsening chaos once American and NATO troops leave, and that the Taliban, which controls about half the country at present, could well become its ultimate arbiter.

The United States has urged the Afghan government and the Taliban to reach a peace accord when their representatives meet at a conference in Turkey from April 24 to May 4.

“It’s important for the Taliban to recognize that it will never be legitimate and it will never be durable if it rejects the political process and tries to take the country by force,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said recently at the end of a one-day trip to Kabul.

In all probability, the Taliban will try to displace the current government and restore the status quo ante in Afghanistan, a scenario that would have been unthinkable two decades ago.