Kiryas Joel, a New York town in the Catskill Mountains 80 kilometres northwest of New York City, is a quintessential European-style shtetl designed to evoke a traditional East European past.

KJ, as it is often called, is inhabited mostly by ultra-Orthodox Jews from the Satmar sect, which was founded by Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum (1887-1979) in the Romanian town of Satu Mare in the early twentieth century.

Established in Orange county in the mid-1970s, KJ quickly became the fastest growing municipality in the state.With 2,000 residents in 1980, KJ was populated by 25,000 Hasidic inhabitants in 2019. By one estimate, its population may well reach 96,000 in 2040.

KJ is the subject of American Shtetl: The Making of Kiryas Joel, A Hasidic Village in Upstate New York, a deeply-researched and cogently-written book by Nomi M. Stolzenberg and David N. Myers published by Princeton University Press.

Stolzenberg teaches at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law, while Myers holds a chair in Jewish history at the University of California in Los Angeles.

In their rigorous yet accessible work, they draw a comprehensive and balanced portrait of a municipality they interchangeably refer to as a village or a town. Formed so that its residents could live a stringently observant religious life, in which public and private matters are guided by its grand rabbi, KJ offers them a rich network of institutions that cater to Satmar traditions and are patterned on the shtetls of Europe prior to World War II.

Their sartorial uniqueness, ritual customs, religious piety and deep reverence for the past conjure up Tradition, the well known theme song of the Broadway play and Hollywood movie, Fiddler on the Roof.

Teitelbaum, after whom KJ was named, barely survived the Holocaust. Satu Mare, which was alternately in Hungary and Romania from 1914 until 1945, was occupied by the German army in the spring of 1944. In May of that fateful year, 18,000 Satmar followers were murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Teitelbaum was rescued and survived in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. After liberation, he lived briefly in Switzerland and Palestine before settling in New York City in 1946.

With a small cadre of supporters, he built up a tight-knit community in Williamsburg in Brooklyn. In addition, the Satmars founded satellite communities in London, Montreal, Antwerp, Montevideo, Melbourne, Jerusalem, Bnei Brak and Kiryas Joel. With a total population of 150,000, the anti-Zionist Satmar haredi sect is now the largest of all the Hasidic sects.

KJ — an autonomous village within the town of Monroe — is special because it fulfills Teitelbaum’s aspiration for a spiritual community separated from non-Jews. Yet, as the authors point out, KJ is decidedly American, rooted in the landscape of the United States and influenced by its social, economic and political currents.

In terms of their political leanings, the Satmars resemble conservative white Christians, particularly Evangelicals. Satmars subscribe to the Christian right’s belief that religious liberty is threatened by the government and that liberal elites are their enemies.

The authors claim the Satmars have shifted from “instrumental pragmatism” to “ideological conservatism” since the 2016 presidential election, when 55 percent of them voted for Donald Trump. In the last election, he received 99 percent! And a small number of haredim even participated in the infamous January 6, 2020 insurrection in Washington, D.C.

“The Satmars’ longstanding fear of assimilation has given way to assimilation into the present-day culture of right-wing libertarianism and anti-government conservatism,” Stolzenberg and Myers conclude.

Most notably, the Satmars have learned the rules of “American interest-group politics” to promote their pet projects and influence politicians. They have become “thoroughly American in their understanding of the game of interest-group politics.”

Comparing them to the Amish and the Mormons, Stolzenberg and Myers contend that what the Satmars have done in KJ is unprecedented in the Diaspora: “In only a small fraction of cities, towns and villages in (Eastern) Europe did the Jewish community constitute a majority of the population. In none of them did the Hasidic Jews constitute the sole group or hold the reins of government. Yet that is exactly what we see in Kiryas Joel, where the Satmars constitute over 99 percent of the population.”

Elaborating on this theme, they argue that KJ represents something new in terms of self-governance — “a self-standing, homogeneous, Yiddish-speaking shtetl that became a legal municipality recognized by the state … and without precedent in European Jewish history.”

But in achieving this objective, the Satmars have been embroiled in more than a dozen lawsuits challenging municipal institutions and practices.

From the moment they arrived in Monroe in 1974, they were not interested in interacting with any of its residents, be they Jewish or Christian. They came to Monroe with the intention of creating a self-sufficient and enclosed enclave. “They had no desire to integrate since assimilation would spell the end of their sacred way of life,” write Stolzenberg and Myers.

There was also another factor at play. “The pervasive assumption that their neighbors were antisemitic reinforced the Satmars’ desire to have as little contact with the surrounding world as possible. They believed that this aspiration was their prerogative as part of the American experiment in cultural pluralism. And they grasped that group segregation was the effect — and, for many, the intent — of the great American move to the suburbs.”

Unlike most suburbanites, the Satmars live in apartment buildings where the density of housing units is seven times that of the regional norm. This was and is a necessity, given their extraordinary high birthrate.

It is not uncommon for Satmar parents to have between eight and fifteen children. Yet the sharing of space is also the product of necessity. According to Stolzenberg and Myers, nearly 50 percent of Satmars live below the poverty line, rendering them very dependent on social security payments and making them one of America’s poorest communities.

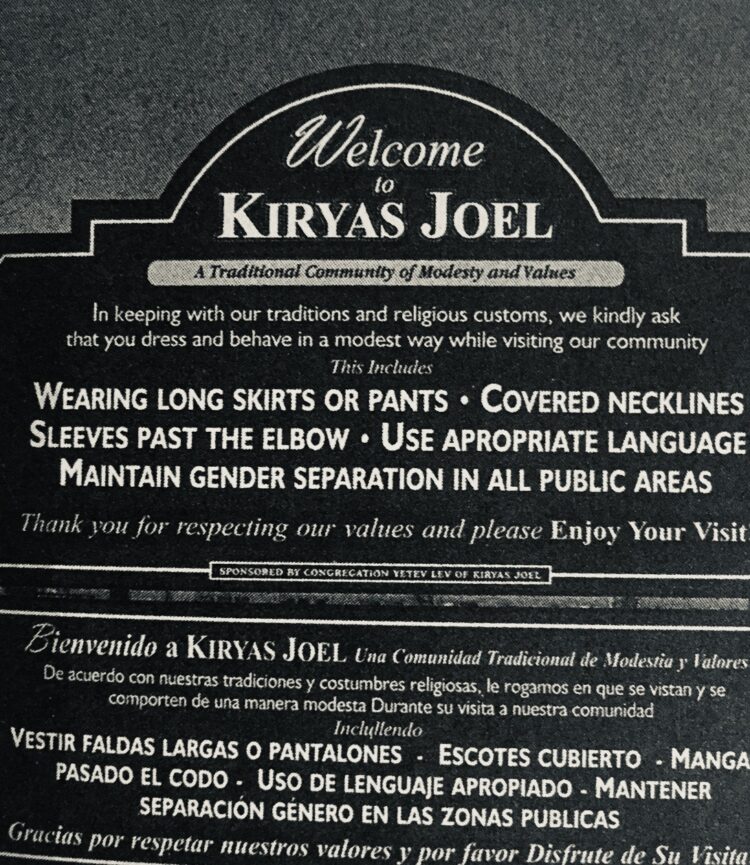

It is a community profoundly steeped in conformity, and the penalty for deviation can be harsh. The commitment to unrelenting uniformity starts with physical appearance. Men wear black pants trailing fringes and plain white shirts. And almost every male sports peyes, or twirled sidelocks. Women are permitted more latitude in their dress, but they cannot appear immodest.

Men and women are paired up in arranged marriages. And while some men are gainfully employed, such as in the Satmar-owned B&H Photo emporium in Manhattan, women are often the breadwinners. Girls receive far more exposure in school to secular subjects such as English. Their fluency in English means they can enter the workplace as secretaries, clerks and office managers. The private school system, however, employs the largest number of people in KJ.

As alien as the Satmars appear to their secular neighbors, their rise has been in step with larger trends in American society. As Stolzenberg and Myers put it, “KJ’s birth coincided with the ascendance … of libertarian ideologies that embraced property rights and juxtaposed the supposed virtues of privatization and localism to the sins of big government.”

Both the U.S. Congress and the Supreme Court have provided considerable wiggle room to individuals and groups who seek to opt out of existing laws in the name of religious freedom. “Orthodox Jews, in particular, welcomed and played an important role in bringing about this shift in attitudes about how to reconcile the principle of separation between state and religion with the principle of religious accommodation.”

In short, as they note, the Satmars “fit into a larger story of diverse religious groups” that have constructed “enclave” communities in the United States.