The first historians to conduct research on the Holocaust in Poland were its Jewish survivors. “They pioneered the study of the Holocaust from the perspective of the Jewish experience,” writes Mark L. Smith in The Yiddish Historians And The Struggle For A Jewish History Of The Holocaust, published by Wayne State University Press.

As he observes in this revelatory book, they have been surprisingly neglected as a group. In his judgment, the most important ones were Philip Friedman, Isaiah Trunk, Nachman Blumenthal, Joseph Kermish and Mark Dworzecki, all of whom he profiles.

They were preceded by such pre-war scholars as Moses Schorr and Meyer Balaban, who held a chair in Polish-Jewish history at the University of Warsaw.

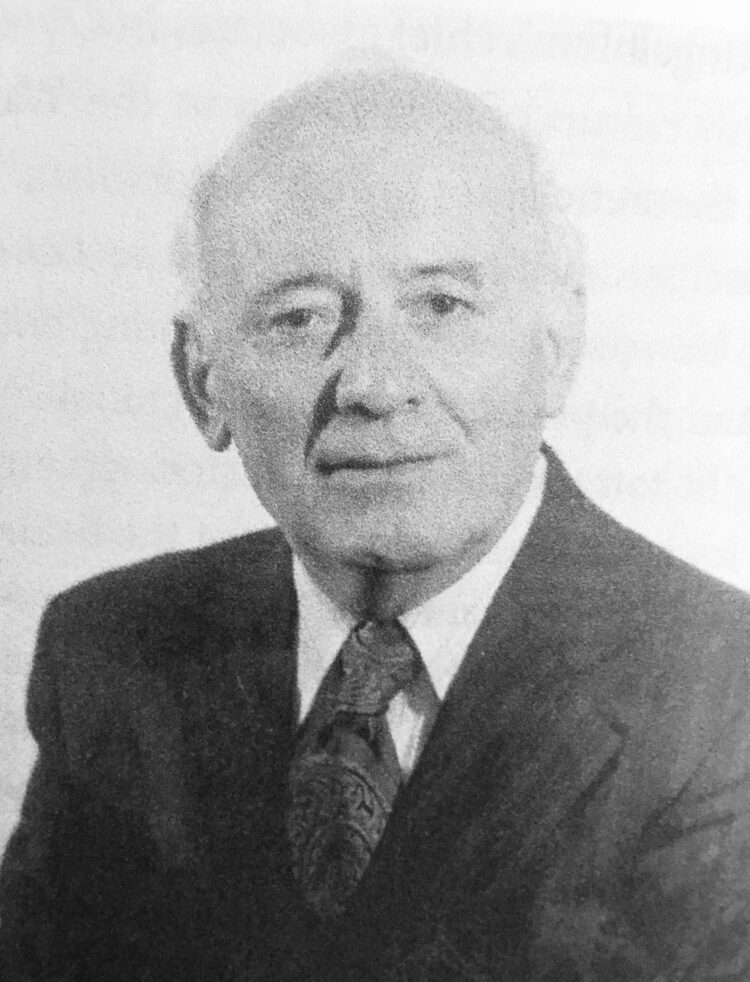

Smith, an American historian who has taught Jewish history at the University of California, designates Friedman (1901-1960) as the undisputed leader of the postwar Yiddish-speaking historians who wrote books and monographs about the Holocaust.

Friedman, unique in having received his higher education outside Poland, earned a doctorate in Central and East European history at the University of Vienna in 1925. “Like all his future colleagues in Holocaust studies, he was not an adherent of the Marxist interpretation of history, and, moreover, he was outspokenly opposed to communism and Soviet influence,” says Smith.

During the Nazi occupation, Friedman survived in hiding in his hometown of Lwow thanks to the assistance of Tadeusz Zaderecki, a Christian Talmudist. After the war, he was the first director of the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland, which was later renamed the Jewish Historical Institute. As well, he was appointed to teach Jewish history at the University of Lodz, the first academic position awarded to a Yiddish historian in Poland.

Friedman immigrated to the United States in 1948. Like many Polish Jews, he was disillusioned with Poland. As Smith puts it, “With increasing Soviet domination of Poland and continuing acts of antisemitism, the Yiddish historians despaired of reconstituting Jewish communal life in postwar Poland.”

He arrived in New York City at the invitation of his friend and teacher, the Columbia University historian Salo Baron. Friedman would become a director of YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research, and the author of, among other books, Martyrs and Fighters: The Epic of the Warsaw Ghetto and Their Brothers Keepers, an account of Christian rescuers of Jews.

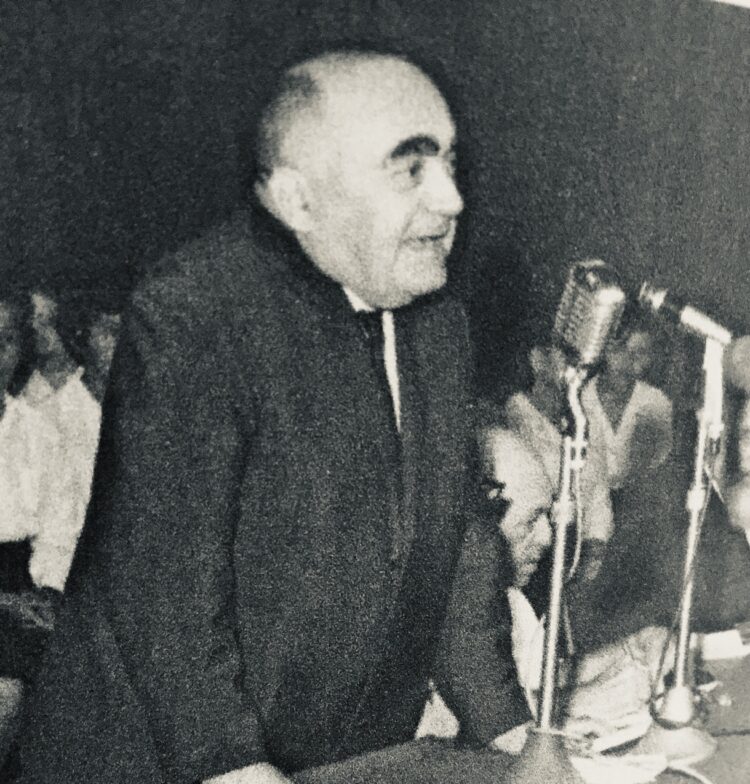

Trunk (1905-1981), who studied under Balaban, was a Jewish secondary school teacher in the interwar period. During the Holocaust, he went into hiding in Bialystok. In the wake of the war, he settled in Canada, where he became the principal of a Jewish Peretz School. In 1954, he joined YIVO as chief archivist and senior researcher.

His magnum opus, Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation, was the first, and only, work of Yiddish scholarship to earn a National Book Award. Trunk’s last major work, Jewish Responses To Nazi Persecution, was hailed as “pathbreaking” by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Blumental (1905-1983), whose last prewar teaching position was at a Jewish gymnasium in Lodz, wrote about Yiddish literature under the Nazi occupation. Among the books he edited were on the Lublin ghetto and the Warsaw ghetto revolt.

Kermish (1907-2005), who received a PhD in Polish history from the University of Warsaw in 1937, took refuge in the Soviet Union during the war. In 1950, he made aliyah and became one of the founders of a Holocaust museum in Israel. He wrote books about the Warsaw ghetto and was the co-editor of a book about Polish-Jewish relations during World War II.

Dworzecki (1908-1975), a physician by training, survived the Vilna ghetto and several concentration camps. He moved to Paris in 1945 and immediately began writing about the Holocaust. In recognition of his work on the Vilna ghetto, which was translated into Hebrew, he was awarded the first Israel Prize in social science.

In addition to his portraits of the aforementioned Yiddish scholars, Smith mentions a few historians who chose to remain in Poland following the war. They included Ber Mark, Artur Eisenbach, the brother-in-law of Emanuel Ringelblum, the diarist of the Warsaw ghetto, and Szymon Datner, all of whom were directors of the Jewish Historical Institute.

“Despite their important early Holocaust works, these historians … became separated from the mainstream of Yiddish Holocaust historiography and had only occasional contacts with their colleagues in the West,” he says.

“During the period of Stalinist purges in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Jewish-oriented Holocaust studies in Poland were discouraged, and the narrative of Jewish resistance and non-Jewish aid to Jews was restricted to the efforts (real and fanciful) of communist partisans and Soviet forces.

“Until the fall of the communist regime in 1989, the historians of the Jewish Historical Institute were subject to the recurring periods of antisemitic agitation suffered by Polish Jews at large. They often found it safer to divert their writing into earlier, less contentious periods of Jewish history.”