Nine months after Adolf Hitler assumed power in Germany, a Polish Jewish socialist named Mikhal Astour published an article in a Warsaw Yiddish journal warning of the dark future that awaited Poland’s 3.3 million Jews and the three million Jews of Hungary, Romania, Latvia and Lithuania.

“That which has happened in Germany … is only a hint of the catastrophe that will break out in those lands,” he prophetically wrote in October 1933. “By the time the storms finally grow still, the Jewish people will be crushed and broken.”

Astour’s prescient essay, which appeared at a moment of relative stability in Poland, was regarded by some observers as jarring and unduly alarmist. But to American historian Kenneth B. Moss, his piece touched a deep chord.

By this point, he writes in An Unchosen People: Jewish Political Reckoning In Interwar Poland (Harvard University Press), a piercing and penetrating analysis of Poland prior to World War II, a significant proportion of Polish Jews had begun “to move toward the conclusion that there was little realistic prospect of a decent future for them in Poland or indeed Europe.”

This grim mood was at odds with the increasing Polonization of Polish Jews from the late 1920s onward, says Moss, a professor of Jewish history at the University of Chicago. “But that period also dramatized as never before that cultural integration and political integration were two very different things, and that the former would not automatically bring the latter and might even be weaponized as an argument against it,” he adds in an important qualification.

Moss convincingly argues that the Great Depression, having produced enormous upheaval and immense fear in Poland, solidified opinion among some Poles from all socio-economic backgrounds that Jews were an alien and malignant minority who blocked their path and that of their children to a better life.

He examines this perception through the lens of Polish nationalism, which was bifurcated along two fundamental lines. Alongside an intolerant and antisemitic ethno-nationalism of the Right, there persisted “an older inclusive vision of the nation with at least some room” for Jews, who comprised 10 percent of the population and more than one-third of Poland’s urban population.

The rebirth of independent Poland in 1918 was accompanied by an upsurge of antisemitic violence, but the “tolerant tradition” prevailed constitutionally, inasmuch as Jews received equal citizenship and rights.

During the era he focuses on, 1926 to 1935, the nationalist Right seemed to be on the ascendancy. But well before this morose juncture, anti-Jewish animus had grown. Rightists assassinated President Gabriel Narutowicz, whom they regarded as a Jewish lackey. And during the 1922 election, the Polish Socialist Party, which normally rejected racism, claimed that its candidates were “real Poles.”

The intolerant and ugly strain of Polish nationalism was exemplified by Roman Dmowski, the head of the National Democracy movement, which grew dramatically from 1930 onward. The Endeks, as they were known, claimed that Jews were an unassimilable element, constituted a state within a state, and posed a grave obstacle to Poland’s national development.

Many of its supporters were university students who triggered anti-Jewish riots, demonstrations and attacks at universities in Warsaw, Lwow and elsewhere from 1929 onward.

Endek operatives also organized boycott campaigns against Jewish merchants. And in cities such as Bialystok, Kielce and Lodz, they encouraged anti-Jewish violence. Adam Blaszczyk, an Endek member of parliament, lauded Nazi policies as a model for how Poland should deal with its Jewish citizens.

The Polish Catholic church, in theory at least, hewed to papal injunctions against national and religious hatred. But in practice, it sympathized with the Endeks, as Moss suggests.

The rector of the Catholic University in Lublin believed that Jews “bound by the Talmud were united together to plot against and destroy other nations.” Parish priests, in general, claimed that Jews were a hostile force. Jews could “redeem” themselves through conversion to Christianity, but generally, the Jews of Poland were seen as a genuinely serious problem by Polish Catholics.

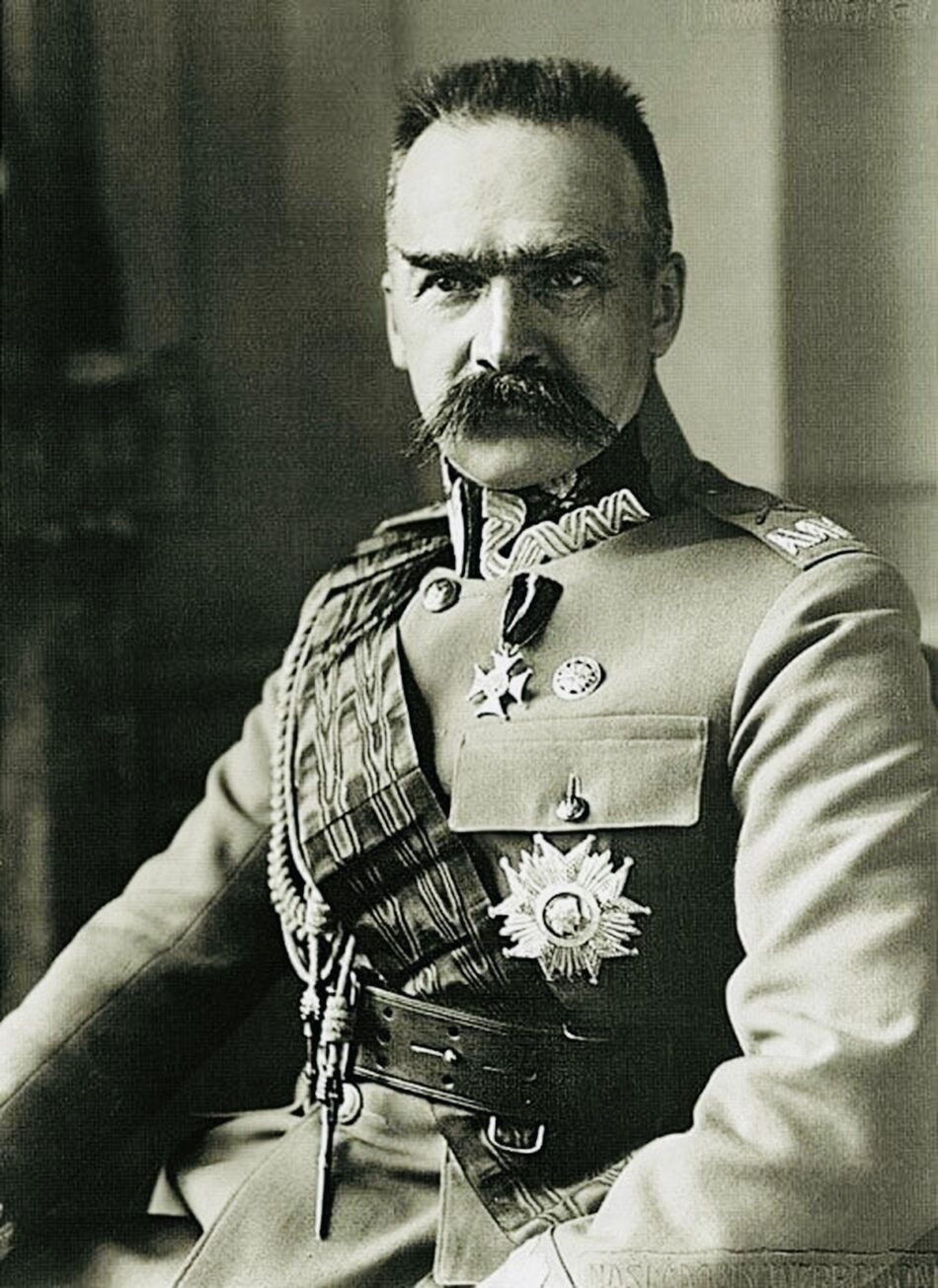

Józef Piłsudski, who ruled Poland from 1926 until his death in 1935, represented the kinder, gentler side of Polish nationalism. His “Sanacja” regime sought to improve the state’s relationship with its minorities — Jews and ethnic Germans and Ukrainians. The coup that brought him to power fed hopes among Jews that the poison of antisemitism could be drained from Poland’s body politic. But as Moss says, Poland’s “Jewish Question,” or kwestia zydowska, grew ever more toxic after 1926 as the Sanacja “proved limited in its capacities to remake Polish political culture.”

Pilsudski dissolved Dmowski’s National Democracy movement in 1933, but could not dismantle the political Right, a subculture of civic and student groups and women’s organizations. And although some of Pilsudski’s supporters were committed to an inclusive vision of Polishness, still others wavered. “There was growing reason to doubt that the regime would even try to impose a tolerant answer to the Jewish Question,” says Moss.

From the early 1930s onward, some top-ranking officials affiliated with Pilsudski adopted the Endecja view that Jews were not full-fledged Poles. In 1934, the chief officer of a major Polish Jewish organization, who had been eager to believe that Jews had a future in Poland, privately said that antisemitism had become so robust that the Sanjacja had to follow the trend.

Boguslaw Miedzinski, the leader of the Sanacja faction in parliament, confirmed this suspicion in an unsettling speech in which he said that its tolerant relationship with Jews stemmed only from “political necessity.” Meanwhile, positive articles about Endek youth were published in the pro-Sanacja newspaper Gazeta polska.

By the mid-1930s, the Sanacja, operating out of the need “to steal the Endecja’s thunder,” had abandoned its commitment to a pluralistic Poland and had openly adopted a policy of “de- Judaization.” The regime endorsed “nativization” of the economy and backed the emigration of most Jews as the only solution to the Jewish Question.

From 1936 to 1937, a massive wave of anti-Jewish violence swept over dozens of towns and villages. “Municipal authorities and police often manifested sympathy for the attackers over the victims,” writes Moss. “The antisemitic-nationalist diagnosis was embraced across wide swaths of Poland’s judiciary, as literally thousands of court cases resulted in light sentences for pogromists, harsh sentences for Jewish self-defence activists, and even sentences against Jews who spoke up. Their crime was ‘insulting the Polish nation.'”

This was an epoch when chauvinism and antisemitism were rampant and “seemed to encounter no open resistance,” the Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz succinctly observed.

These troubling developments did not necessarily mean that Polish Jews were utterly imperilled. As Moss puts it, “No one can make that pronouncement … It is not my argument that all Polish Jews felt this way. Many continued to believe that traditions of tolerance in Polish political culture would win out eventually.”

The leader of the socialistic Bund, Henryk Erlikh, still believed that class struggle would bring revolution and resolve the Jewish problem. Socialists, in particular, claimed that the situation would improve in the future.

Throughout Poland, substantial numbers of Jews aspired to be fully Polish. And in cities such as Krakow and Warsaw, there were distinct communities of Polonized Jews for whom Polishness was a non-negotiable value and who considered themselves deeply patriotic “Poles of the Mosaic faith.”

Yet a worrisome proportion of Jews felt uneasy in Poland, Moss notes.

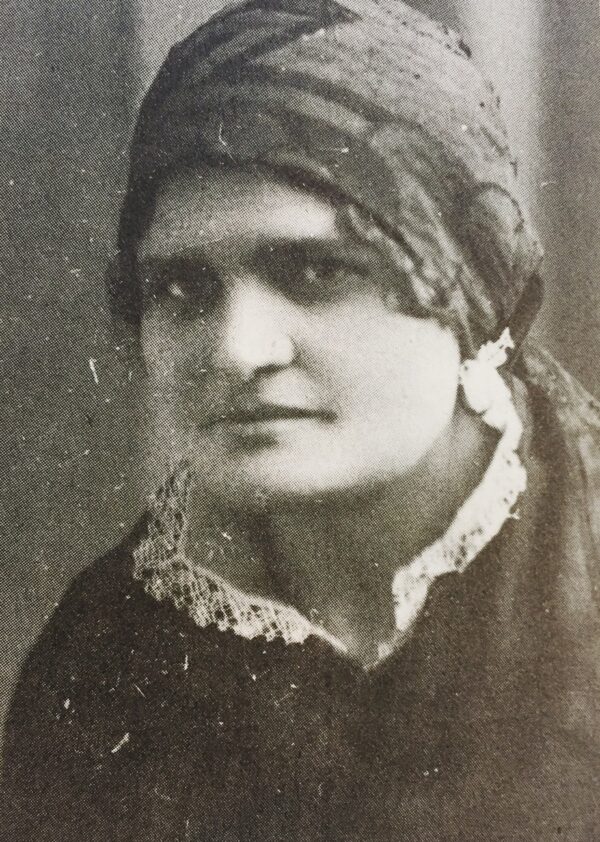

Travelling through Poland in 1928 and 1929, the journalist Rachel Faygenberg concluded that the “chief reality” of Polish Jewish life was “deep despair,” and that among Jewish youth there was a desire to emigrate.

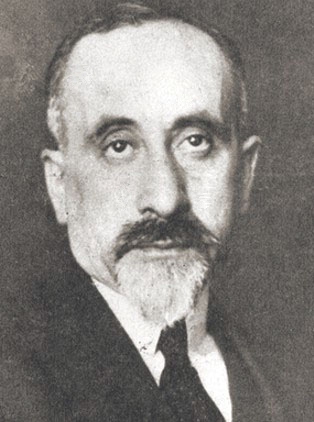

In 1930, Jacob Appenszlak, the Warsaw editor of the Polish-language Jewish newspaper Nasz Przeglad, proclaimed that much of Polish Jewry, whether laborer, industrialist, professional or intellectual, had experienced a sense of “ghettoization” within “invisible yet impassable boundaries.”

In 1931, after a decade in Palestine, the folklorist Alter Druyanov returned to Poland on behalf of the Jewish National Fund. Charged with writing a report about Polish Jews, he warned that they were gripped by angst and a feeling of futurelessness regarding their prospects in Poland: “The Polish Jew … lives in constant fear — not without reason — lest his tomorrow be still darker,” he said.

Another Zionist activist, Lova Levita, returned to Poland in 1929 after spending five years in Palestine and, much to his surprise, he discovered that young people who were joining Zionist youth movements were not necessarily driven by ideology or idealism but by an emerging conviction of Jewish futurelessness in Poland.

“Levita found the same sensibility in some of Poland’s most Polonized Jewish communities,” writes Moss. “Travelling through the storied old towns of Czestochawa, Kalisz and Sieradz … he found Jewish youth who studied overwhelmingly in Polish state schools, (possessed) no knowledge of Hebrew to speak of, and linguistic Polonization proceeding so fast that some young people who attended his discussions could not understand Yiddish.”

Levita also noticed that some members of Zionist youth groups hailed from non-Zionist (Bundist) and anti-Zionist (communist) backgrounds.

Moss elaborates on this theme: “Poland’s relatively stable regime sat atop a magma of hostilities and tensions … Though the anti-rightist Sanacja regime consolidated its hold on political institutions, the larger political culture was ever more permeated … by ethnic-nationalist enmity, conspiracy thinking and visions of radical societal transformation through mass politics and violence.”

By Moss’ estimation, 400,000 Jews permanently left Poland between 1921 and 1938. And by 1939, 200,000 Jews had officially informed the Jewish Agency of their serious interest in settling in Palestine. Among the Jews who already had gone to Palestine was Shmuel Lakerman, a Bundist and a Yiddishist who had given up on the idea of remaining in Poland.

Moss thinks many more Jews would have emigrated had they received foreign visas. “Most obviously, substantial parts of the world had no interest in East European Jewish immigration and worked actively to forestall it,” he says.

Surveying the “pogrom mood” in Poland in 1931, the sociologist Jakob Lestschinsky noted that the main unanswered question on the minds of many Jews was where they could possibly resettle.

That many Jews sought to uproot themselves and begin anew abroad was a telling commentary on the state of Jewish-Polish relations, which Moss accurately describes as “a 500-year history of troubled yet intimate entanglement ended only by the Holocaust.”

In this outstanding work of scholarship, Moss delves into a complex and depressing issue with verve and a mastery of the topic.