It was a visit like no other in Israel’s history.

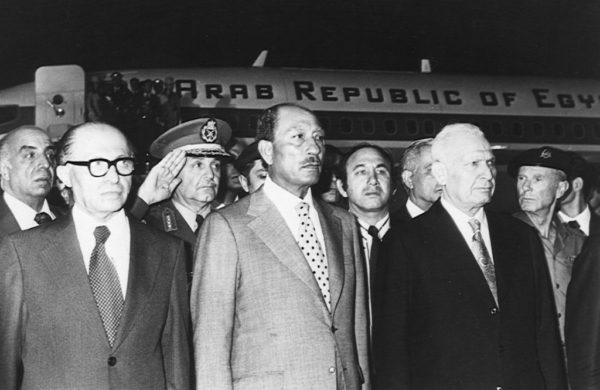

Forty years ago, on November 19 at 7:59 p.m., a Boeing 707, code-named Egypt 01, landed at Ben-Gurion Airport, one minute ahead of schedule. Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, had arrived in Israel, the first Arab head of state to set foot in the Jewish state.

Only four years earlier, Israel and Egypt had been locked in mortal combat in the Yom Kippur War, which exacted a fearsome toll on both sides.

Now, in an astonishing turn of events that shocked and angered Arabs, Sadat entered the lion’s den, determined to break the costly cycle of animosity and violence that had pitted Israel against Egypt in five wars and numerous skirmishes.

Israelis were generally euphoric, hoping that Sadat’s trip might be a precursor to ending the long-running Arab-Israeli dispute. But some Israelis, still reeling from Egypt’s surprise attack on the first day of the 1973 war, were paranoiac. The chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces, General Mordechai Gur, warned Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin that Sadat’s historic visit could well be a devilishly clever cover for something far more sinister.

Disregarding Gur’s warning, Begin received Sadat with all the ceremonial trappings befitting such a momentous occasion, including a 21-gun salute.

As Sadat, clad in a light grey suit, descended from the aircraft, he was met by Israeli President Ephraim Katzir, Begin, members of his cabinet, army generals and a host of Israeli political celebrities. When he greeted Golda Meir, who had been prime minister during the Yom Kippur War, he said, “Madam, I have wanted to meet you for a long time.” When he ran into Ariel Sharon, the general who had turned the tide of the war in the Sinai Peninsula, he said, “I was hoping to trap you over there.”

Once the ceremony ended, Sadat and Katzir were driven to Jerusalem in a black bullet-proof limousine borrowed from the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv. Sadat spent the remainder of his time in Jerusalem, conferring with Begin and his ministers, visiting the Al Aqsa Mosque in the eastern sector of the city and addressing the Knesset.

Sadat’s trip to Israel was carefully planned.

In mid-September of that auspicious year, Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan met the Egyptian deputy prime minister, Hassan Tohami, in Morocco to discuss that very possibility. Tohami, having learned from Dayan that Israel was ready to vacate the Sinai in return for peace, reported the news to Sadat, who believed the Arab-Israeli conflict was 70 percent psychological and 30 percent substance.

Before the 1973 war, Sadat had begun to radically realign Egypt’s foreign policy.

In 1971, a year after he succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser as president, he offered Israel peace in exchange for a full withdrawal from the Sinai. The following year, he loosened Egypt’s relationship with the Soviet Union — its chief arms supplier and principal source of diplomatic support — by expelling 25,000 Russian advisors. Having concluded that what had been taken by force could only be restored by military means, he launched the 1973 war in coordination with Syria to regain the Sinai and the Golan Heights. He embraced the United States as an alternative to the Soviet Union. He worked with U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and U.S. President Richard Nixon to facilitate Israeli withdrawals from Sinai.

By 1977, with the United States and the Soviet Union planning a Middle East peace conference in Geneva, he was poised to take his biggest leap forward.

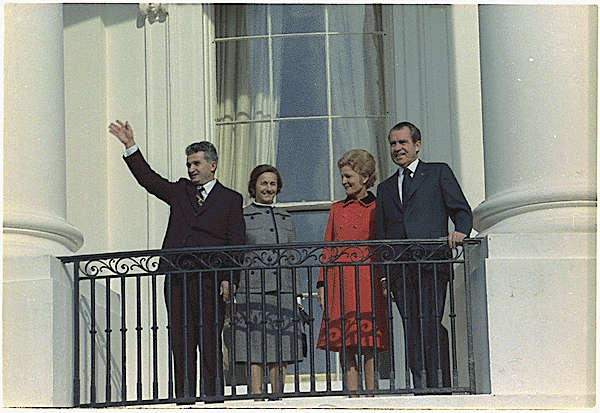

On a visit to Romania — the only Soviet bloc country that had not severed diplomatic ties with Israel during or after the 1967 Six Day War — Romanian President Nicolae Ceausescu persuaded Sadat that Begin sought a rapprochement with Egypt and that he would abide by the terms of an accord.

On November 9, Sadat delivered a speech in which he promised to go “to the ends of the earth,” even to the Knesset, to end the wars that had consumed the lives of thousands of Egyptian soldiers and sapped its economy. On November 11, Begin formally invited Sadat to Israel, an invitation he accepted two days later.

Sadat’s decision caused a firestorm in Egypt and the Arab world.

Egypt’s foreign minister, Ismail Fahmi, resigned as politicians from the semi-tolerated opposition urged Sadat to reconsider. Syria denounced Sadat’s go-it-alone diplomacy as a “painful blow to the Arab nation, a defiance and fragmentation of its national solidarity.”

The only Arab counties that refrained from attacking Sadat were Jordan, Morocco and Sudan.

The Palestine Liberation Organization blasted Sadat as a traitor who would violate “the dearest and most scared goals” of the Palestinians. In Beirut, a leading Lebanese newspaper, al-Safir, compared Sadat to Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, and Arthur James Balfour, the British foreign minister after whom the 1917 Balfour Declaration is named.

Ignoring the fire and the brimstone, Sadat ventured forth to Israel, certain that his remarkable gesture could usher in an era of peace and prosperity for Egypt, a nation proud of its past but mired in the grip of underdevelopment and poverty.

Addressing the Knesset, he offered assurances to Israelis. As he put it, “Today I tell you, and declare it to the whole world, that we accept to live with you in permanent peace based on justice.”

But in a reference to the Palestinians, he said, “The Palestinian problem is the core and essence of the conflict and that, so long as it continues to be unresolved, the conflict will continue to aggravate, reaching new dimensions. In all sincerity, I tell you that there can be no peace without the Palestinians. It is a grave error of unpredictable consequences to overlook or brush aside this cause.”

And in a comment that irked Begin and like-minded politicians, Sadat said that Israel had to withdraw to its pre-1967 border and accept Palestinian self-determination.

Begin, in his speech, did not even mention the Palestinian question and reiterated his belief that the West Bank rightfully belonged to Israel rather than to the Palestinians.

It was clear that Israel and Egypt were far apart on the key issues, but when Sadat returned to Cairo, he claimed his visit has shattered ”all barriers of doubt, mistrust and fear.” He was too sanguine. In the months ahead, Egypt’s bilateral negotiations with Israel bogged down over differences on the Palestinians and other issues. Frustrated by the impasse, Sadat condemned the Israelis as stiff-necked.

Jimmy Carter, the president of the United States, broke the deadlock at the Camp David summit in Maryland in September 1978, a two-week marathon that yielded agreements on ”a framework for peace.” The intensive talks that followed produced Israel’s 1979 peace treaty with Egypt, the first such agreement between Israel and an Arab state. It, in turn, led to Israel’s complete withdrawal from the Sinai and to Palestinian autonomy talks that went nowhere.

Sadat paid dearly for his vision and courage. On October 6, 1981, the eighth anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, he was assassinated by homegrown Islamic fundamentalists as he reviewed a “victory” parade in Cairo. His vice-president, Hosni Mubarak, survived the onslaught and replaced Sadat.

Israel’s official relationship with Egypt, cool and limited for the past 38 years, has weathered a series of storms. But since the military coup of 2013, which brought Abdul Fatah al-Sisi to power, Israel and Egypt have upgraded their covert cooperation in intelligence gathering to combat an upsurge of Islamic terrorism in the Sinai.

On the grassroots level, Israel remains unpopular with the vast majority of Egyptians, due in part to the unresolved Palestinian problem. But thanks to Sadat, Israel forged peaceful relations with the most powerful and influential nation in the Arab world. As the scholar Martin Kramer tellingly reminds us, Egypt and Israel now have been at peace longer than they were at war.