Founded in the 19th century as a manufacturer of brewing and malting equipment, J.A. Topf and Sons branched into a new business in the 1930s. From that point onward, the family-owned company, based in Erfurt, Germany, began producing industrial-scale ovens and ventilation systems to meet a growing demand for human cremations, a more modern, regulated and hygienic way of death.

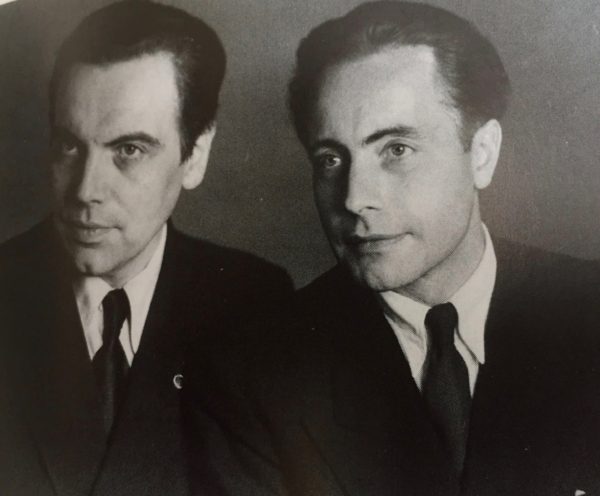

As World War II approached, the company’s chief principals, Ernst Wolfgang Topf and his brother, Ludwig, its commercial and technical directors, started working with the Nazi regime.

In May 1939, Topf and Sons received its first commission from the Nazi state when the SS, the feared police force, ordered three mobile, oil-heated cremation vans to incinerate the corpses of political prisoners at the Buchenwald concentration camp. During the next two years, the SS bought four double-muffle ovens for the Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau and Mauthausen camps.

This terrible and efficient machinery of death, an integral component of the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe, brought in a tiny proportion of Topf and Sons’ profits, yet it would define the company and its legacy, and, as Karen Bartlett writes in her superb book, Architects of Death (Biteback Publishing), it would ensure that Topf and Sons would live in infamy.

As she notes, the company was profoundly complicit in Adolf Hitler’s Final Solution: “Auschwitz evolved from a backwater camp for Polish prisoners to a site for Soviet prisoners of war and finally into a vast forced labor complex and the heart of the planned extermination of the Jewish race in Europe. And far from being mere ‘camp suppliers,’ it was the innovation and flexibility of Topf and Sons that enabled this transformation.”

From the very outset, Topf and Sons was involved in helping the SS devise new means of disposing of its victims. “From 1940 onwards, Topf and Sons took part in discussions and decisions about ventilation systems for the crematoria — and by 1943 it was developing ventilation technology for the gas chambers. In essence, Topf and Sons was devising more efficient ways of murdering people.”

The Topfs and their key employees, ranging from managers to oven fitters, could truly be described as the engineers of the Holocaust.

Curiously enough, as Bartlett points out, neither Ernst Wolfgang nor Ludwig Topf had displayed any signs of overt antisemitism before the advent of Nazism, had a long history of dealing with Jewish families, and joined the Nazi Party in April 1933 out of pure opportunism. Bartlett, a British journalist, gives their association with Jews little credence. “Given that (Topf and Sons) spared no effort in technologically advancing the Holocaust, it is hard to imagine a more breathtaking lie than Ernst Wolfgang’s claim that (it) was, in fact, a friend to the Jews.”

It is true, however, that Topf and Sons employed two people of partial Jewish ancestry, protecting them from Nazi persecution, she says.

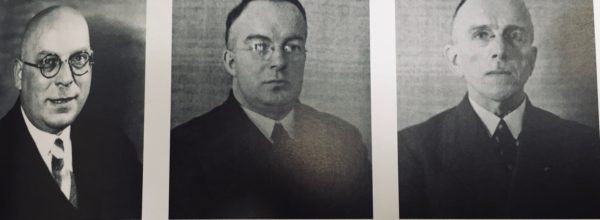

Bartlett contends that Kurt Prufer, the head of its oven construction and cremation department, was the key guiding force of its descent into moral malfeasance. “Without his singular focus, technical skills and drive to better himself, it is doubtful that Topf and Sons would have developed the expertise to become market leaders in crematoria, or that the company would have forged such a mutually beneficial partnership with the SS,” she says.

But as much as he could be held responsible for designing the technology to facilitate mass murder, Prufer was part of a team of experts who had sold their souls to the devil.

Fritz Sander, the manager of the furnace construction division, created a design for crematoria with “greater corpse-cremation capacity.” After the war, he justified his behavior by claiming he had an obligation to use his knowledge to help Germany to victory, even if that resulted in the deaths of millions of civilians.

Sander, though, was not a Nazi. Nor was he ever heard expressing antisemitic sentiments. “Sander’s motives were driven by pure jealousy and dislike of Kurt Prufer,” says Bartlett.

Sander’s colleague, Heinrich Messing, was a technician whose task was to install the ventilation system for the gas chamber and undressing room in the cellar of Auschwitz’s second crematorium. His fellow worker, Karl Schultze, a ventilation expert, spent five months in Auschwitz in 1943 installing the equipment that was so crucial in the annihilation of Jews.

Despite their crimes, Ernst Wolfgang and Ludwig Topf evaded justice.

Shortly after Germany’s defeat, Ludwig purchased potassium cyanide at a local pharmacy and committed suicide. He left a self-pitying letter behind. “If I have decided to avoid arrest, then it is for this reason,” he wrote. “I no longer believe there is any justice in this world … I never did anything consciously and deliberately bad … As a decent man, I now have the opportunity to do with myself as I see fit. That means to depart from this world, which has become generally unbearable, has persecuted me and has been unjust to me in particular.”

Ernst Wolfgang fared better than his brother. He died in 1979 at the age of 74, having evaded police investigations.

Topf and Sons was declared ownerless and expropriated by Soviet occupation forces toward the end of 1945. Prufer and Sander, among others, were arrested by the Soviets, transferred to a prison in Moscow and interrogated.

Astonishingly enough, Prufer claimed he did not know “anything about the real purpose of the crematoria in the concentraption camps” until 1943. When he discovered the “real purpose” of the crematoria, he told his interrogators, he considered ending his involvement in the project. He stayed on because he feared losing his job and suffering reprisals from the Nazis.

Prufer was sentenced to 25 years of hard labor in the Soviet Union. He died of a stroke in 1952. His colleagues also received stiff sentences, but two were released from prison after nine years.

In 1947, Topf and Sons was nationalized by the new, pro-Soviet East German government and renamed VEB. The Topf family did not receive compensation. Nine years later, the company stopped making cremation ovens and focused on manufacturing municipal incinerators. In 1963, VEB was formally dissolved.

With the fall of communism, the Topf family reclaimed the company, but it went bankrupt in 1996. In 2003, Topf and Sons was listed as a protected national monument by the state of Thuringia. On January 27, 2011, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army, the main administration building was declared a memorial open to visitors.

I visited the site in 2013. Its chilling austerity and commitment to truthfulness left an impact, as has Bartlett’s remarkable book.