To its credit, the highest criminal appeals court in Argentina has reopened a murky and convoluted case relating to the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentina’s history, the bombing of the Jewish community center in Buenos Aires on July 18, 1994.

In a unanimous decision recently, the Court of Cassation decided to reopen a file turning on allegations that the former president, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, and her foreign minister, Hector Timmerman, among others, conspired with Iran to cover up Iran’s role in the bloody incident, which killed 85 people and injured more than 200.

Since the majority of victims were Jews, this was the most serious antisemitic crime since the Holocaust. It occurred less than two years after Israel’s embassy in Buenos Aires was bombed, killing 29 people and injuring over 200.

This case has convulsed Argentina, home to the largest Jewish community in Latin America, for more than two decades now.

In the wake of the bombing, the Argentinian Intelligence Service released a report claiming that Iran had planned the attack and that its ally and surrogate, Hezbollah, had carried it out in collusion with local Arabs from the Argentina-Brazil-Paraguay border region.

The decision to bomb the community center was supposedly taken by Iran’s supreme spiritual leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the then president, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (who died on January 8), the then foreign minister, Ali Akbar Velayati, the then intelligence and security affairs minister, Mohammed Hijazi, and the then intelligence minister, Ali Fallahian.

Even after these explosive findings were released, the case continued to be investigated by the Argentinian government. Critics claimed its inquiries were sloppy, if not incompetent, and were characterized by a pattern of coverups.

In 2004, a full 20 years after the bombing, Argentina’s president, Nestor Kirchner, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s husband, appointed Alberto Nisman, a prosecutor, to take a deeper look. In 2006, Nisman confirmed that the culprits were indeed Iran and Hezbollah, both of which vigorously denied the accusation.

Upon Nestor Kirchner’s death in 2007, his wife assumed his position and held it until 2015. Two years before leaving office, she and Timmerman reached an understanding with Iran that the 1994 bombing would be jointly investigated. The agreement was never implemented, having been declared unconstitutional.

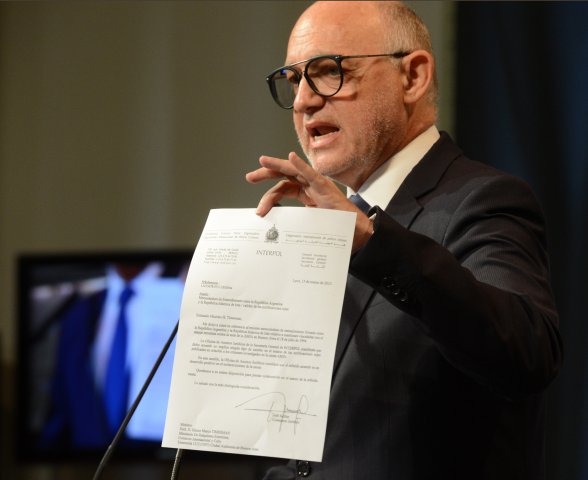

Nisman, however, continued to dig deeper. On January 18, 2015, he was due to brief legislators about a secret deal Kirchner and Timmerman had allegedly concocted with Iranian officials. Under the agreement, the Argentinian government would grant immunity to the planners and attackers of the bombing in exchange for a lucrative trade agreement between Argentina and Iran.

Nisman never appeared at the briefing. He was found dead in the bathroom of his apartment with a gunshot wound in his head. Some commentators claimed he had committed suicide, which sounds far-fetched. In any event, Nisman’s mysterious death still remains unsolved.

Subsequently, Nisman’s allegations were dismissed by a federal judge, Daniel Refecas, who said there was not “even circumstantial evidence” to implicate Kirchner in wrongdoing. Refecas’ verdict was upheld by an appeals court as well as by the Court of Cassation.

This past August, DAIA — the biggest Jewish community organization in Argentina — presented Refecas and the appeals court with new evidence suggesting that Nisman had been correct in casting suspicion on Kirchner and Timmerman.

Acting on this information, the Court of Cassation reopened the case toward the end of December, saying it deserves “a diligent and exhaustive investigation” and “a quick and efficient resolution.”

It remains to be seen whether Kirchner and Timmerman will pay a legal price for their wheeling and dealing. Kirchner, who’s already been indicted on corruption charges relating to public works contracts, claims the accusations against her are false and that her successor, Maurcio Macri, is trying to settle a political score with her.

Not surprisingly, the Iranians are also indignant.

Velayati, now an advisor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, claims that Nisman’s allegations regarding Iran are baseless. And he said, “We recommend Argentina not fall under the influence of the Zionists.”

Judging by the damning evidence collected so far, it seems apparent that Iran and Hezbollah planned and perpetrated the 1994 attack and that Kirchner and Timmerman were ready to turn a blind eye to Iran’s crimes in return for landing a favorable trade deal.

It goes without saying that this case should be pursued until the full truth emerges. It cannot be swept under the rug and forgotten.