Ariel (Arik) Sharon was an iconic warrior and politician, an Israeli who exemplified the rough-hewn patriotism, tenacious fighting spirit and stubborn spirit of a nation born in and shaped by war.

Sharon died in Tel Aviv on Jan. 11 at the age of 85, eight years after a massive stroke felled him.

A Sabra whose life was the mirror image of a country besieged by Arab enemies, he was Israel personified: direct, brash, bold, inventive, outspoken, warm, sentimental and abrasive.

A young officer in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, he rose through the ranks in the 1950s as Israel reacted to Arab attacks by launching punishing reprisal raids into Jordan, Egypt and Syria. As the commander of a special army unit created for this purpose, Sharon led these retaliatory raids, which sometimes resulted in high civilian casualties.

A prodigy of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first and probably greatest prime minister, he played a major role as a general in the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War, both of which altered the political landscape of the Middle East. On both occasions, Sharon distinguished himself as a daring tactician and strategist.

Once his military career ended, Sharon segued into the rough and tumble of politics. Under the premiership of Menachem Begin and successive right-wing prime ministers, Sharon was by turns minister of agriculture, housing, infrastructure, industry, defence and foreign affairs, a central figure in the right-wing Likud party.

A secular nationalist who had grown up in an austere farming village on the Sharon plain, Sharon was a hawk for much of his career, having been one of the architects of Israel’s much-maligned settlement policy in the territories the Israeli army had captured in the Six Day War.

In connivance with like-minded nationalists like Begin, Moshe Dayan and Yigael Yadin, Sharon changed the face of the West Bank, building a maze of Jewish settlements there in the mistaken belief that they would enhance Israel’s security and preempt the emergence of a sovereign and geographically contiguous Palestinian state.

Sharon was the chief planner of Israel’s ill-conceived 1982 invasion of Lebanon, which turned into a disaster. The war embroiled Israel in a quagmire from which it could not fully extricate itself until 2000, heightened tensions with Israel’s ally, the United States, and temporarily ruptured Israel’s pivotal relationship with Egypt, the only Arab state that had signed a peace treaty with Israel.

Israel’s adventure in Lebanon also cost Sharon his ministerial job and cast a pall over his integrity. The Kahan Commission found him personally responsible for allowing the Phalange, a Lebanese Christian militia aligned with Israel, to massacre hundreds of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

An ardent opponent of territorial compromise and a two-state solution, he believed that the Palestinian problem could be resolved by establishing a Palestinian state in Jordan.

From the outset, he railed against the Olso peace process, which was championed by his old comrade-in-arms, Yitzhak Rabin, who paid the ultimate price for his somewhat dovish views. But after his election as prime minister in 2001, Sharon grew more cautious as he gradually shifted to the center of the political spectrum and away from the complacent status quo.

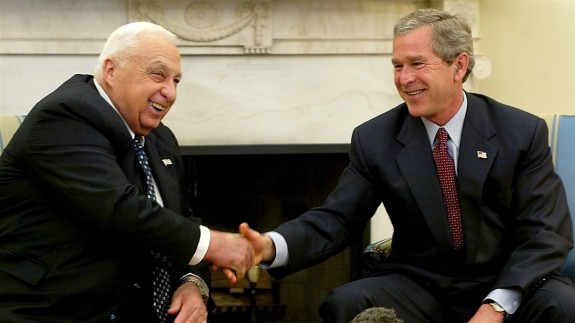

By now, he belatedly realized that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza was incompatible with its desire to remain a democratic and Jewish state and a factor in Israel’s growing unpopularity and isolation abroad. Sharon never really became a fullblown peacenik, but he strongly believed it was in Israel’s interest to separate itself from the Palestinians. Sharon’s volte face earned him the admiration of U.S. President George W. Bush, who called him “a man of peace.”

Before Sharon addressed the gnawing Palestinian issue seriously, he dealt firmly with the second Palestinian uprising, which had broken out in September 2000, shortly after his provocative and politically-motivated visit to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, claimed by Jews and Muslims.

Sharon cracked down hard on Palestinian suicide bombers, who wreaked havoc in Israel, and took steps to render irrelevant the leader of the Palestinian Authority, Yasser Arafat, his long time nemesis. At the end of March 2002, after a Palestinian terrorist detonated a bomb in a Netanya hotel that claimed the lives of 30 Israelis, Sharon activated Operation Defensive Shield, Israel’s biggest military thrust into the West Bank since the Six Day War.

Israel reoccupied major towns like Nablus, Jenin and Ramallah, leaving the Oslo accords in a shambles and the Palestinians further away from their goal of statehood.

Once the dust had settled and the scourge of suicide bombings had receded, Sharon began building a multi-million dollar separation fence along the twisting length of Israel’s border with the West Bank. Much of the barrier was erected inside the West Bank, splitting up Arab neighborhoods and farms and prompting well-founded accusations that Israel was unilaterally grabbing land that rightfully belonged to the Palestinians.

With the construction of the barrier well in hand, Sharon announced his intention to withdraw unilaterally from Gaza. Israel’s settler lobby hotly denounced Sharon’s policy as a betrayal, and in a sense, they were right. Sharon, in his hawkish phase, had convinced Begin to build a string of settlements in Gaza, though he had also issued orders for the demolition of Israeli settlements in the Sinai. And now, purely for pragmatic reasons relating to the demographic imperative threatening Israel, Sharon was intent on evacuating 21 settlements in Gaza, as well as three in the northern West Bank.

Sharon opted for a unilateral approach out of a misguided belief that Israel had no Palestinian negotiating partner. Israel’s pullout from Gaza in the summer of 2005, a significant change in direction for Israel, emboldened Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement. In June 2007, Hamas proceeded to seize Gaza from Fatah — a mainstream Palestinian faction headed by the moderate Mahmoud Abbas — in a violent coup.

Sharon’s Gaza strategy was vehemently opposed by many of his colleagues in the Likud party, notably Benjamin Netanyahu. Feeling like strangers in a strange land, Sharon and his loyalists, including Ehud Olmert and Tzipi Livni, bolted the Likud to form Kadima, a centrist party.

Not in the best of health in recent years, Sharon suffered a mild stroke in December 2005. Less than a month later, he fell into a coma after suffering a massive stroke. He spent the next eight years in a vegetative state, his two headstrong sons refusing to let him go.

Had Sharon lived and won another election, he might have withdrawn from the West Bank, or at least from much of it. His successor, Ehud Olmert, was well on his way toward forging a peace agreement with his Palestinian counterpart, Mahmoud Abbas, when a scandal forced him out of office and brought Netanyahu to power for the second time since 1996.

In hindsight, Sharon was a man of war and a man of peace.

He was a tough, courageous and dedicated soldier, but as a politician, he often lacked vision and espoused reckless and short-sighted policies. But toward the end of his life, he finally saw the light.