The often ironic, self-mocking Jewish joke has been endlessly exploited by two diametrically different forces in modern Germany. Jews have used it as a release mechanism to lighten the heavy burden of rejection and discrimination. Antisemites have resorted to it to belittle and defame Jews.

This dichotomy is examined and analyzed by Louis Kaplan — a professor of visual studies at the University of Toronto — in his book, At Wit’s End: The Deadly Discourse Of The Jewish Joke, published by Fordham University Press.

Kaplan, a member of the University of Toronto’s Centre for Jewish Studies, deals with three chronological periods: the Weimar Republic from 1918 to 1933, the Nazi interregnum from 1933 to 1945, and the postwar period following the Holocaust.

“The transformation of suffering into laughter constitutes a Jewish cultural tradition and has served as a personal ethos for a large part of my life,” he writes. “I owe this unwavering attitude to my father, Leon Kaplan, who has served as a role model for my brother and myself in many ways.”

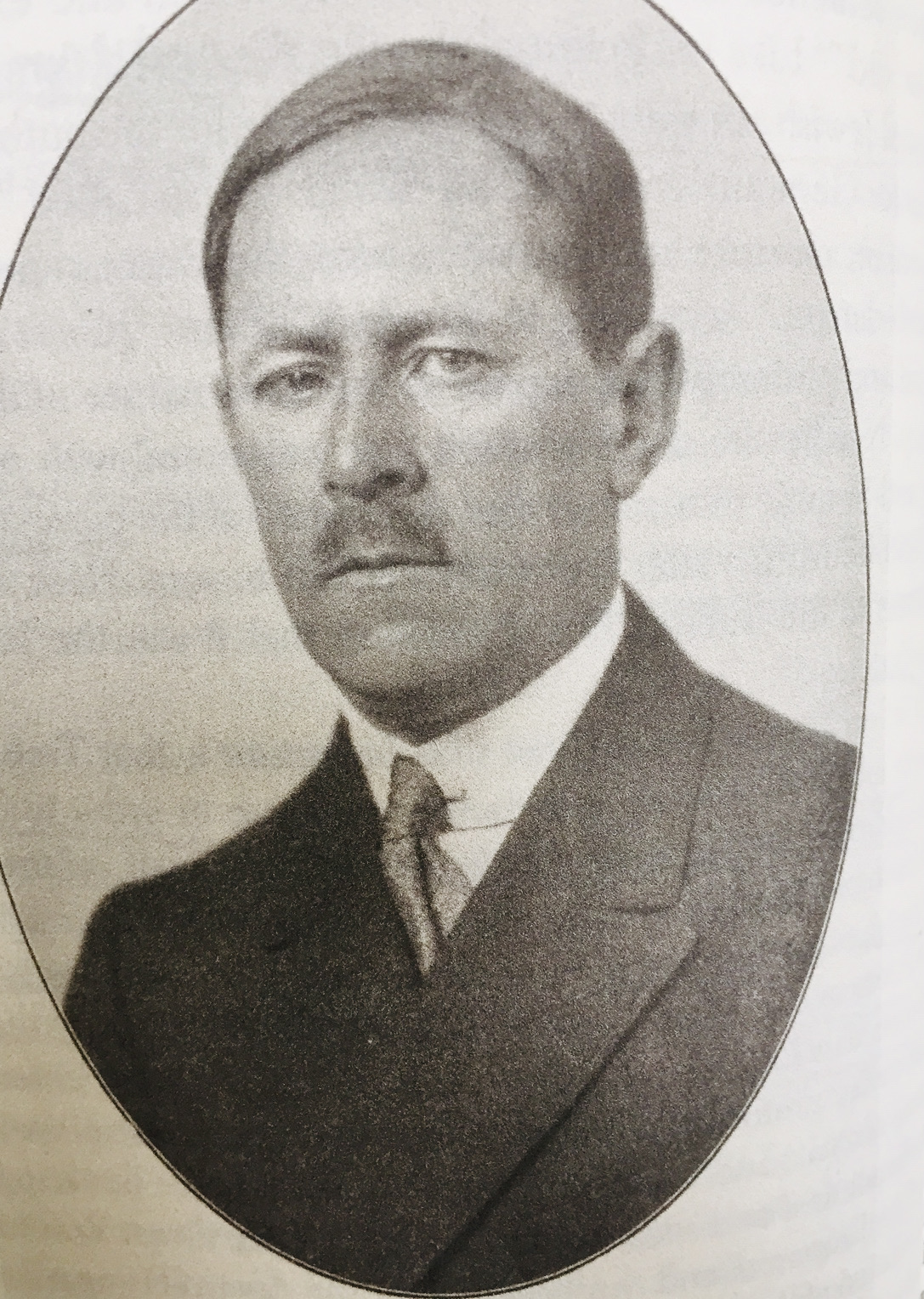

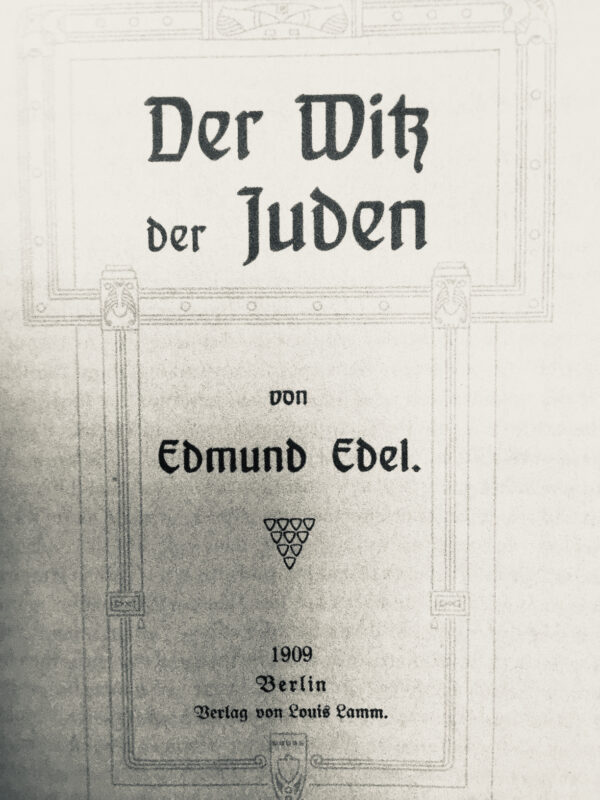

The author begins his survey with comments on the Berlin-based commercial illustrator and caricaturist Edmund Edel (1864-1943), who in 1909 published Jewish Wit, the first monograph on the Jewish joke in the German language.

As he wrote, “The Jew not only loves to make fun of others, but also does not shy away from ironizing his own personality at every opportunity. This self-irony of the Jews has created a huge mass of excellent observations and jokes.”

Kaplan shares Edel’s belief that Jewish humor, at least within the context of German history, was often a response to antisemitism and provided an outlet through which Jews could convert humiliation into laughter.

Ultimately, Judenwitz, or Jewish wit, was “not the affirmation of any particular social, political or moral agendas but the ironic deflation of all such agendas,” Edel says. “Judenwitz was the voice of the disengaged individual who saw the world in absurdist terms.”

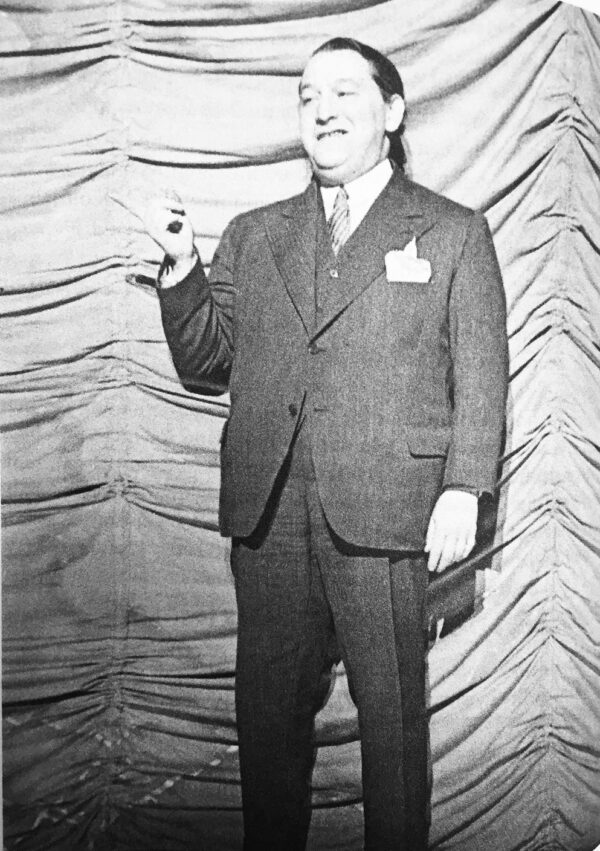

As the renowned Weimar-era comedian and cabaret director Kurt Robitschek was fond of saying, Judenwitz was the last weapon of the defenceless, a means by which to disarm the antisemitic enemy through jokes.

Not everyone, of course, appreciated the Jewish joke.

Alfred Wiener, a Jewish community notable, regarded it as morally depraved and akin to antisemitism.

Arthur Trebitsch (1889-1927), a Viennese-born Jewish antisemite whom Adolf Hitler respected and even considered appointing the Nazi Party’s official ideologue, argued that Judenwitz was a deceptive and diversionary tactic by which Jews concealed themselves.

Trebitsch, the son of a wealthy silk merchant, was a classic self-hater who denied his Jewish identity and who was an early supporter of the National Socialists. Like the Nazis, he believed in Aryan superiority and contended that World War I was caused by an international Jewish conspiracy.

During the Third Reich, the Nazi regime appropriated self-deprecating Jewish jokes into its antisemitic propaganda campaigns.

Hitler was certainly aware of Judenwitz. Delivering one of his trademark fiery speeches at a Nazi Party assembly in Nuremberg in 1934, he reiterated his intention to deal harshly with Jews. “Then he’ll be at his wit’s end,” he thundered. “The time is already at hand that he’ll be treated as he was treated hundreds of years ago.”

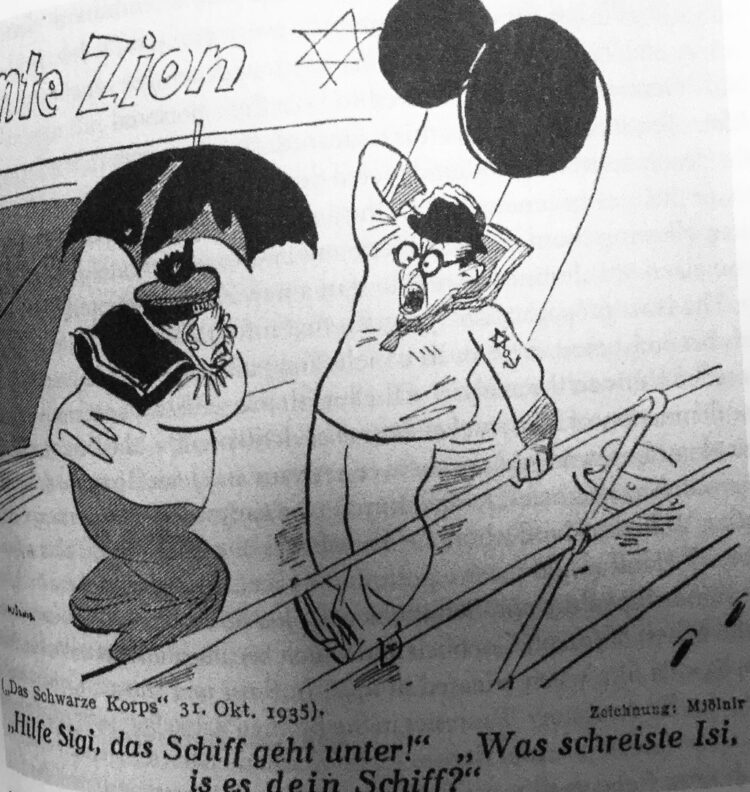

In one of its 1935 editions, the magazine Das Schwartze Korps published a caricature of two Jews abroad the Monte Zion, a ship en route to Palestine. It reads: “Help, Ziggy. The ship is sinking! What are you screaming for, Izzy? Is it your ship?”

In postwar West Germany, the Swiss Jewish philosopher Salcia Landmann published Der judische Witz, which stayed on the bestseller list for months. Kaplan believes that the success of Landmann’s book rested, in part, on a genuine philosemitic desire by some Germans to revive the spirit of Judenwitz.

I have mixed feelings about Kaplan’s book. While it examines a relatively obscure yet noteworthy topic in German-Jewish historiography with rigor and probity, Kaplan’s turgid academic style will attract few readers.