When he was 13 years old, Canadian playwright Jason Sherman received an unusual bar mitzvah gift — a tree planted in his name in Israel by the National Jewish Fund. The JNF, as it is known, is a non-governmental, non-profit charitable organization based in Jerusalem which plants forests and develops land in the Jewish state.

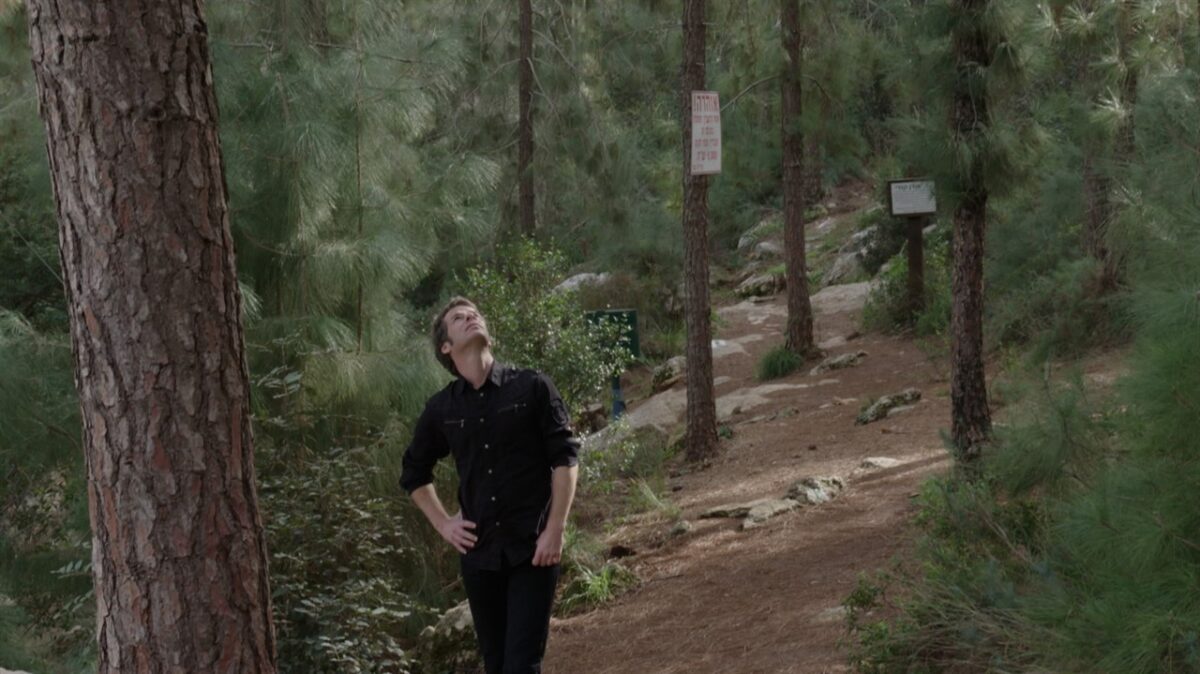

Decades later, Sherman decided to find that tree, which, he believed, connected him to Israel. But how could he possibly track down one of more than 200 million trees that have been planted by the JNF since its inception more than a century ago?

The odds were stacked against him, but he pulled out all the stops in an effort to locate it. Sherman’s odyssey began in Toronto, took him to Israel, brought him back to Canada and, finally, prompted him to visit the United States.

It was an exhausting, frustrating, revelatory and disillusioning journey. It all unfolds in Sherman’s riveting documentary, My Tree, which will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation from October 14-17.

A resident of Toronto, he starts his search by combing through family mementos in vain. Finally, he stumbles upon the JNF tree certificate ascribed with his name at Beth Tikvah synagogue, the venue of his 1975 bar mitzvah. But where is the actual tree? Obsessed by this burning question, he books a flight to Israel.

Sifting through documents at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem, he fails to hit pay dirt. Visiting the Neve Ilan Forest, he finds nothing. Enlisting the help of Ishai Schuster, a kibbutz gardener, he learns that the Jerusalem pine — a fast-growing and highly flammable tree with shallow roots favored by JNF afforestation projects — may well be his tree.

Buoyed by the information, Sherman goes to a JNF nursery, but receives no cooperation.

Alon Rothschild, an official with the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, drives him to a likely site, the Nachshon Forest, but Sherman comes up empty.

Not one to give up, he pays a visit to Canada Park, a popular 700-hectare Canadian-funded reserve about halfway between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. In all probability, his tree is somewhere here.

His guide in Canada Park is Eitan Bronstein-Aparicio, the founder of We Remember. An Israeli organization founded in 2002, it is dedicated to raising awareness of the Nakba, the displacement of Palestinian Arabs from their homes and properties in 1948, and of documenting human rights violations against Palestinian refugees.

Bronstein-Aparicio tells Sherman that Canada Park was built on the ruins of three strategically-located Palestinian villages — Imwas, Yalo and Beit Nuba — in the West Bank that were captured and then bulldozed and dynamited by the Israeli army on the orders of its chief of staff, General Yitzhak Rabin. Prior to their destruction, its inhabitants were expelled.

“All these are war crimes,” says Bronstein-Aparicio, clearly upsetting Sherman. “Palestinian history is denied here.”

Having absorbed this unsettling information, Sherman meets Uri Davis, the co-author of the book The Jewish National Fund. To Davis, the JNF is a “charity complicit with ethnic cleansing.”

Next, Sherman speaks to Haim Noach, the executive director of the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civic Equality. In her view, the JNF plants trees to control the land and dispossess Palestinian Arabs. Noach introduces Sherman to a bedouin whose family lands were expropriated by Israel. To him, every JNF tree represents a crime against Arabs.

Sherman’s reaction is one of shock and dismay: “I came to Israel to find my tree, an innocent abroad, and now all that innocence has been stripped away.”

Returning to Toronto, Sherman talks to Rabbi Miriam Margles of the Danforth Jewish Circle, hoping for rabbinical guidance to assuage the “crime” and the “injustice” that were committed in his name when his tree was planted in Israeli soil. The rabbi describes his quest as “an exploration of the truth.”

Sherman interviews John Goddard, a journalist who wrote the first article about Canada Park. It appeared in a 1981 edition of the magazine Saturday Night. Goddard is a supporter of Israel who cannot ignore inconvenient facts. “Canada Park is built on a lie,” he declares, claiming that Canadian donors were unaware that it sits on land owned by dispossessed Palestinians.

Attempting to be balanced, Sherman tries to arrange an interview with a JNF official. He declines, claiming that Sherman has “politicized” the issue. Sherman is now convinced he’s “an accomplice to a coverup.”

He then meets two Jewish brothers who launched an unsuccessful campaign to delist JNF as a charity because it may have violated the Income Tax Act.

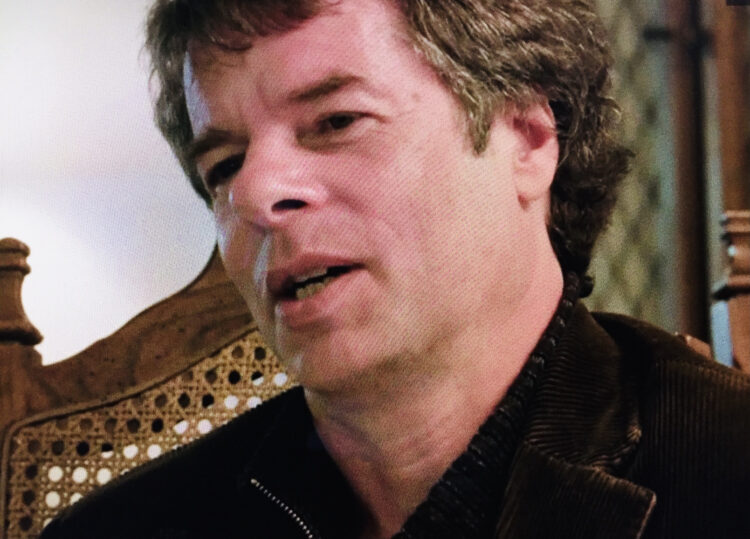

Struggling to come up with his own response to JNF’s activities, he flies to Vancouver to meet Harris Gulko, the former Canadian national director of the JNF who dreamed up the concept of Canada Park several decades ago. Claiming he does not remember having seen Palestinian villages in what is now Canada Park, Gulko says, “There was never a Palestine.” As the interview proceeds, Gulko grows increasingly uncomfortable and fidgety.

Sherman is thunderstruck by this meeting, calling himself “a 13-year-old boy who has been used for a dark purpose.”

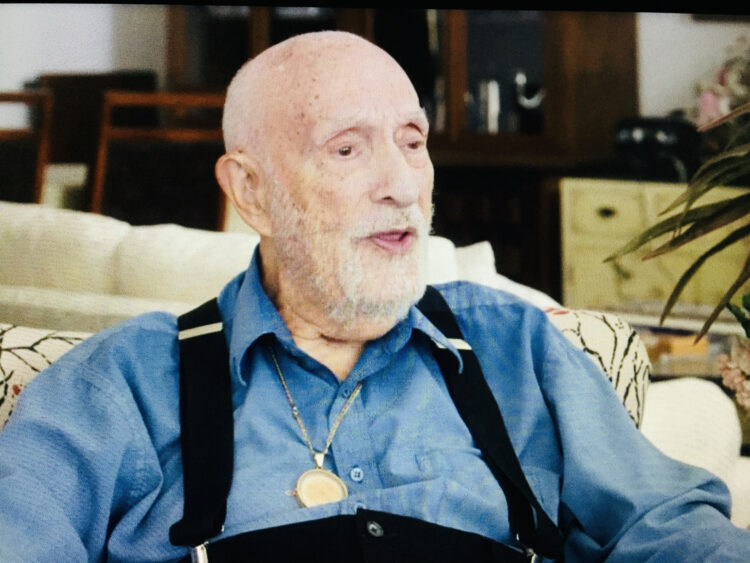

With the film winding down, Sherman visits Mohye Abdulaziz in Tucson, Arizona, a Palestinian American whose family was driven out of the village of Imwas. “This was my world,” he says plaintively. “We never thought something so drastic would happen.”

Abdulaziz visited Canada Park and discovered the remnants of his family’s house. As far as he is concerned, the park “celebrates my destruction.” Sherman is deeply touched, tears falling down his face as he listens to Abdulaziz’s account of displacement.

By telling his own story, Sherman, in effect, is telling Abdulaziz’s story.