It could be one of the shortest political comebacks in Israel’s history.

Ehud Barak, the former prime minister of Israel, has returned to politics after a seven-year hiatus. He hopes to play a starring role in unseating Benjamin Netanyahu, the current Israeli premier and his former boss, in the September 17 general election.

It’s questionable, however, whether Barak can achieve this objective, much less win a seat in the Knesset.

Now 77, Barak is counting on name recognition to further his political ambitions. One of Israel’s most distinguished public figures, he certainly possesses an impressive resume.

Lest it be forgotten, Barak trounced Netanyahu to win the premiership. As prime minster from 1999 to 2001, he unilaterally withdrew Israeli troops from southern Lebanon, tried but failed to reach a peace agreement with Syria and the Palestinian Authority, presided over the collapse of the 1993 Oslo peace agreements, and struggled to squelch the second Palestinian uprising, which erupted in 2000.

Before this, he was foreign minister and defence minister. In a storied career, he was also the chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces and a decorated army officer.

Most recently, Barak entered the political arena after a long absence. In announcing the formation of the left-of-center Israel Democratic Party at the end of June, he urged like-minded parties to join him. “These are dark days the likes of which we have not known before,” he said. “The Netanyahu regime must be toppled.”

Shortly afterward, Barak — who was Netanyahu’s commanding officer in the elite Sayeret Matkal commando unit and his defence minister — shook up things again.

As widely expected, he shuttered the Israel Democratic Party and formed a new party, the Democratic Camp, an alliance consisting of the left-wing Meretz Party, led by Nitzan Horowitz, and of a single parliamentarian, Stav Shaffir, who bolted from the left-of-center Labor Party to partner with Barak.

Before Meretz agreed to the merger, Horowitz demanded an apology from Barak for the deaths of 12 Israeli Arabs shortly after the second Palestinian rebellion broke out in September 2000. They were killed by Israeli police after the eruption of rioting in Israeli Arab communities in support of the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The demand for an apology was reportedly made by Issawi Freij, the only Arab representing Meretz in the Knesset.

Barak delivered an apology promptly, admittng he bore responsibility for the tragic events of October 2000. As he said, “There should be no situation in which demonstrators are killed by the fire of the security forces of their own country.”

With the apology behind him, Barak negotiated a merger agreement with Meretz. Horowitz was named leader of the Democratic Camp and received its number one slot. Shaffir, having lost her bid to defeat Amir Peretz as head of the Labor Party, was given the two spot on the new slate.

Barak, at his apparent insistence, was placed way down on the list, in 10th place. It’s debatable why he sacrificed himself in this manner.

Pollsters have predicted that the Democratic Camp may win up to eight parliamentary seats in the election — which means that Barak may well be deprived of a seat in the next Knesset. If that scenario pans out, Barak will be consigned to the political wilderness, his attempt at a comeback thwarted.

The Democratic Camp certainly has high hopes. At their first press conference, Barak and his colleagues promised to work hard to unseat Netanyahu. “We are embarking on a path that … will lead to replacing the current leadership and bringing about social change,” said Horowitz, the first openly gay leader of an Israeli political party.

The Democratic Camp will fight the “racism, corruption, occupation and religious coercion” of Netanyahu’s right-wing government, he pledged.

Barak was unable to convince the Labor Party and the centrist Blue and White Party, led by Benny Gantz, to merge with the Democratic Camp. Peretz, who instead forged an alliance with the centre-right Gesher Party, still bears a grudge against Barak. Barak defeated him in the 2007 Labor Party leadership race, only to leave the party four years later and form a centrist party that became part of Netanyahu’s ruling coalition government. Some people in the Labor Party, like Peretz, have never forgiven Barak for this betrayal.

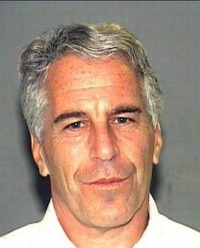

Gantz, whose party won 35 seats in last April’s election, may have been deterred by the Jeffrey Epstein scandal in the United States. Barak, following his retirement from politics in 2012, established a business relationship with Epstein, an accused sex offender. Barak’s image was further tarnished when the Daily Mail, a British daily, published a photograph of him waiting to enter Epstein’s home in New York City, his face partially hidden by a scarf and a hat, allegedly for a sex party.

Barak’s association with Epstein may have sullied his reputation to some extent, but it remains to be seen what the verdict of the Israeli electorate will be come next month.

In the meantime, Barak is convinced that the Democratic Camp can have a meaningful impact on Israel’s future. “This is the first step toward … replacing the government and safeguarding Israel as Zionist, Jewish and democratic,” he said.