Germany’s preeminent newsmagazine, Der Spiegel, carried a story on the Jewish community of Germany in one of its latest special editions. On its cover was a vintage photograph of two elderly ultra-Orthodox Jews clad in traditional caftans. The Central Council of Jews in Germany, in a tweet, objected to the illustration, saying it perpetrated antisemitic stereotypes. “To portray Jews as foreign or exotic promotes antisemitic prejudice,” it said.

I fully agree.

That this respectable mass-circulation magazine saw fit to view the mostly secular Jews of Germany through the lens of Hassidic Jews is bizarre, to say the least. Der Spiegel‘s representation of Jews is so skewed that it feeds into anti-Jewish tropes.

There are, to be sure, ultra-Orthodox Jews in Germany, but they are not representative of Germany’s wider Jewish community. They are but a minuscule minority in contemporary Germany, an insular, closeted and pre-modern sect whose values, outlook and mode of dress are largely, if not completely, at odds with the average Jewish person in the country.

From the emancipation of German Jews in 1871 until their systematic persecution by the Nazi regime after 1933, German Jews made immense strides in integrating themselves into mainstream society. Historians have documented this phenomenon in voluminous detail, and there is no need to regurgitate it here.

Antisemitism never disappeared during the course of this epoch, however, and one can argue that the advancement of German Jews galvanized the malevolent and seething forces of antisemitism in Germany.

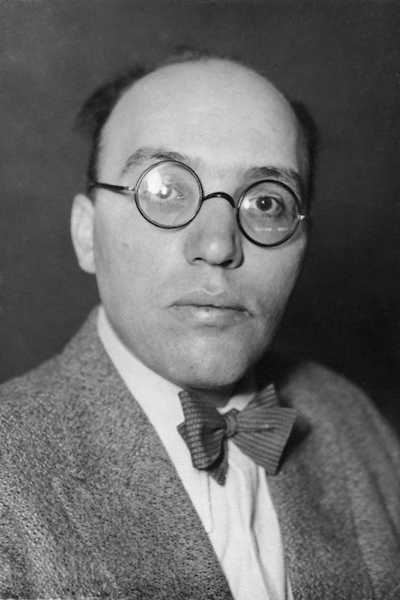

German Jews who achieved prominence tended to be highly assimilated and included such stellar figures as the scientists James Franck and Paul Ehrlich; the film director Ernst Lubitsch, the theater director Max Reinhard, the painter Max Liebermann, the composer Kurt Weill, and the industrialist Walther Rathenau, Germany’s first and still only Jewish foreign minister.

German Jews from their socio-economic milieu were so acculturated that mixed marriages and conversions to Christianity were not uncommon. The Jewish community in the last third of the 19th century and the first third of the 20th century was deeply steeped in German culture and intensely patriotic. During World War I, 12,000 Jewish soldiers were killed.

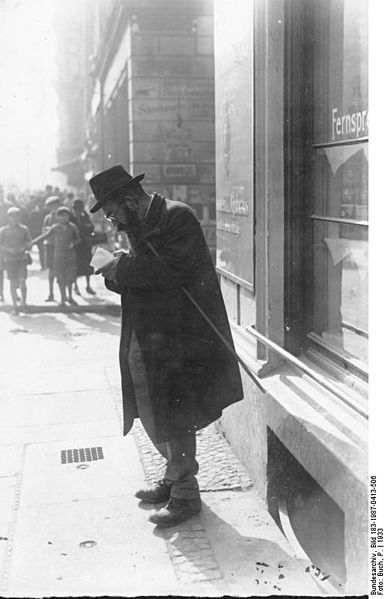

Ultra-Orthodox Jews, hewing to ancient customs and traditions, were very different, living their lives as centuries before and not venturing boldly into society. Most of them, from the impoverished shtetls of Eastern Europe, arrived in Germany after World War I and settled in the rundown but colorful Scheunenviertel district of Berlin.

The antisemitic propaganda that inundated Germany after its surrender to Allied forces in 1918 focused, in part, on these ultra-Orthodox newcomers, who were regarded as foreigners and outsiders.

The vast majority of German Jews in Berlin lived in far more prosperous and sedate neighborhoods.