Lior Sternfeld, a professor of history and Jewish Studies at Pennsylvania State University, has written a nuanced work on Iran’s Jewish community and Israel’s relations with Iran. These are highly-charged topics, given Iran’s hostility to Israel since the 1979 Islamic revolution and the sometimes precarious position of Jews in Iranian society.

In his book, Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth-Century Iran, published by Stanford University Press, Sternfeld provides readers with an absorbing account of Iran’s evolving relationship with Israel and of its venerable Jewish community, the largest in the Middle East outside of Israel.

There has been a Jewish presence in Iran, a nation of minorities, since the Assyrian exile in 722 BCE. Defined by Islam as the People of the Book, Jews were allowed to practice Judaism relatively freely as long as they paid a special tax and complied with various restrictions.

Jews routinely suffered harassment and forced conversions under the Safavid and Qajar dynasties from the 18th to the 20th centuries, yet vast numbers of Jews voluntarily converted to Islam, Christianity and Bahaism during these periods, he points out.

With the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 to 1911, Jews attained equal status with Muslims, but the real breakthrough occurred only after Reza Khan’s ascendance to the throne in the 1920s. A modernizer who attempted to create a secular state, he brought relief to the Jews of Iran, but in the strict spirit of secularism, he closed Jewish schools.

Nonetheless, 80 percent of Iranian Jews lived in impoverished conditions in rural areas or on the outskirts of big cities, reported the American Joint Jewish Distribution Fund in 1941. Only 10 percent belonged to the urban middle class, and an additional 10 percent were wealthy.

Islamic exclusionary practices affected Jews of every class, but Iran’s close relations with Nazi Germany did not have an adverse impact on its Jewish citizens. During World War II, 150,000 Polish refugees entered Iran, of whom 1,800 were Jews. Iraqi Jews had migrated to Iran during World War I.

Under the monarchy of Reza Khan’s son, Mohammed Reza Shah, the demographic picture of Jews changed radically. On the eve of the overthrow of the Pahlavi royal dynasty, 80 percent of Iran’s 100,000 Jews belonged to the upper middle class. Only 10 percent of Jewish Iranians were poor.

“In the decades leading to the 1979 revolution, the Jews of Iran were decisively integrated,” Sternfeld writes. “This integration manifested itself in the Jews’ upward social mobility, their visibility in the public sphere, and their prominent place in the Iranian economy, science and various political projects.”

“Jews were part of every walk of life in Iran, visible, prominent and integrated,” he adds.

Among them was the industrialist and philanthropist Hajji Habib Elqaniyan, who enhanced Tehran’s budding skyline with the construction of the 17-storey Plasco high-rise building, the tallest one in the city.

Sternfeld argues that the Pahlavi era was the golden age of minorities in Iran, but he claims that the majority of Jews did not appear to support the continuation of the monarchy. Sternfeld’s assertion is at odds with the conventional view that the Jewish community was favorably disposed to the Pahlavi dynasty.

He goes on to say that the left-leaning Jewish intelligentsia took no interest in Jewish affairs and were not Zionists.

Five thousand to 12,000 Jews participated in one of the biggest street protests against the Shah on December 11, 1978. Muslim demonstrators greeted Jews by chanting, “Jewish brother, welcome, welcome.”

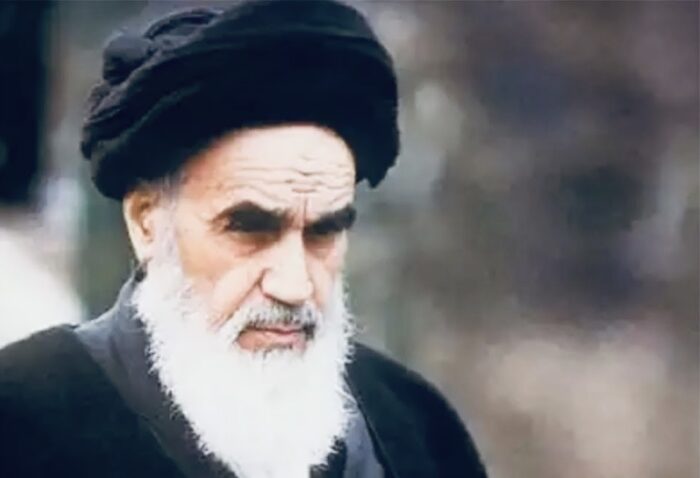

Some protesters wounded by police fire were treated at the Sapir Hospital, a Jewish facility. In appreciation of its assistance, the leader of the Islamic opposition, Ayatollah Khomeini, sent a letter of gratitude to its director, Dr. Siamak Moreh-Sedeq.

A Jewish delegation in that year visited Khomeini in Paris. “The tacit purpose of this trip was to ensure that Jews would not be regarded as enemies of the revolution but rather as its supporters,” says Sternfeld. “This meeting was the first of many between the Jewish leadership and Khomeini.”

These meetings, which sought to draw a distinction between Jews and Zionists, “secured the future of Jews” under Khomeini’s leadership, he notes.

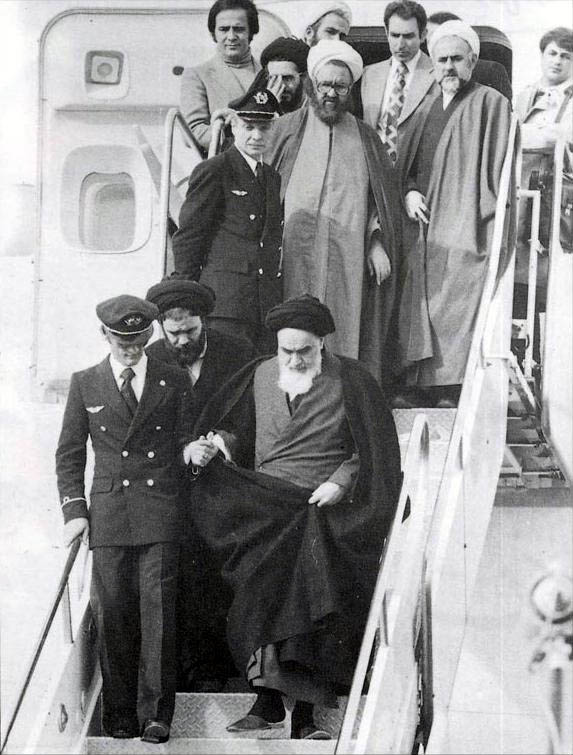

And when Khomeini returned to Iran after a lengthy exile in France, a Jewish delegation was at the airport to welcome him back home.

Yet there were bumps on the road as Jews tried to fit into the new political order. Elqaniyan was executed in May 1979, having been convicted of spying for Israel and acting against Islam and the revolution.

Several days after his execution, a small Jewish delegation went to Qom to meet Khomeini. According to reports in the Iranian media, their encounter established the ground rules regarding the Muslim relationship with Jews.

“Khomeini distinguished between Judaism and Zionism, allegedly ending the widespread speculation that all Jews were undercover Zionist agents,” says Sternfeld. “In a proclamation, Khomeini acknowledged the deep roots of Iran’s Jewish community, underscored the elements of monotheism in both Judaism and Islam, and distinguished between Zionism and Judaism.”

Khomeini stated disingenuously that Zionists could not be equated with Jews. In his twisted opinion, Zionists are “politicians” who “hate Jews” and claim “to work in the name of Judaism.”

Like Zoroastrians, Jews were given one seat in parliament, in accordance with the size of their community. By Sternfeld’s estimate, Iran is home to 25,000 Jews today.

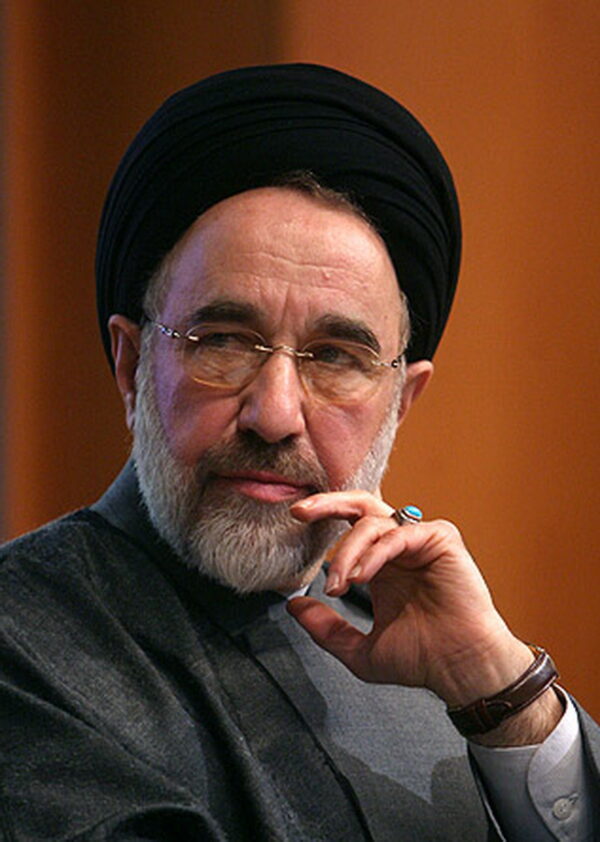

Iranian politicians after Khomeini’s death in 1989 generally treated Jews with respect. President Mohammad Khatami paid an official visit to a synagogue in Tehran. The current president, Hassan Rouhani, has sent Rosh Hashanah greetings to the Jewish community. Rouhani’s predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was an exception to the rule. His descent into Holocaust denial was met with resistance by Maurice Motamed, the Jewish deputy in parliament.

To prove their undying loyalty to Iran, Jewish leaders supported the Iranian war effort against Iraq from 1980 to 1988 and adopted a strong pro-Palestinian position.

Jewish youths were encouraged to join the armed forces. Jewish soldiers killed in the line of duty are memorialized in a mural in Tehran unveiled in 2014.

The Jewish community aligned itself with Iran’s harsh policy toward Israel, staging protests against Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and publishing articles in a community magazine comparing Zionists to Nazis.

Iran recognized Israel in 1950, allowing Zionist organizations to operate openly and granting exit visas to Jews making aliyah. From 1947 to 1951, some 25,000 Jews, the poorest in the community, immigrated to Palestine and Israel. Iran also permitted Indian, Pakistani, Iraqi and Afghan Jews to cross Iranian territory en route to Israel.

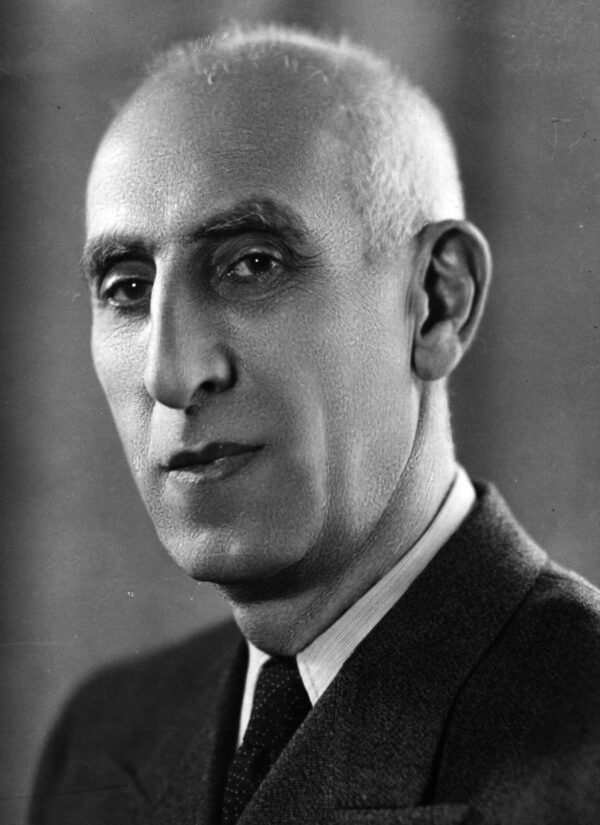

Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq, severed relations with Israel in 1951 in the hope of garnering Arab endorsement for his nationalization policy. Jews continued to immigrate to Israel during this period. When he realized that Arab states would not support him, he tried to establish trust with the Israeli government by offering Israel cheap oil for 25 years. Israel declined his offer.

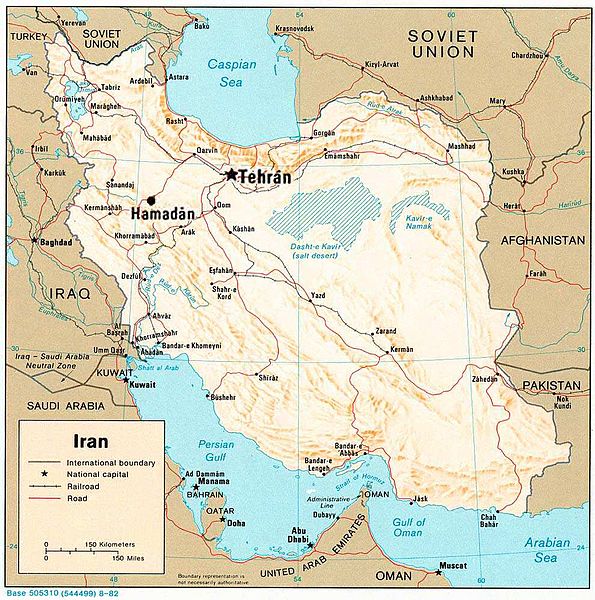

After Mosaddeq’s fall, Iran formed an alliance with the United States. “Iran would become a key outpost for the West in the Middle East, providing strategic access to the Caspian Sea and Persian Gulf and standing as an ally directly on the Soviet Union’s southern border,” says Sternfeld.

Iran’s relations with Israel improved considerably after the 1967 Six Day War. By the 1970s, a myriad of Israeli companies maintained offices in Iran, while El Al Airlines operated 18 flights per week between Tel Aviv and Tehran.

On a grassroots level, however, Israel was unpopular. Sternfeld claims that the Israeli flag was never flown over Israel’s embassy in Tehran. And he cites a 1968 incident during which the Israeli national soccer team was escorted by police out of a stadium to avoid mob violence.

With the downfall of the monarchy, Iran broke diplomatic relations and handed over the Israeli embassy to the Palestine Liberation Organization. Since then, Iran has been one of Israel’s most vocal, persistent and dangerous enemies.

In closing, Sternfeld suggests that the remaining Jews of Iran do not plan to leave, barring some disaster. As he puts it, “They choose to stay because Iran is their homeland and Zion is their direction of prayers.”