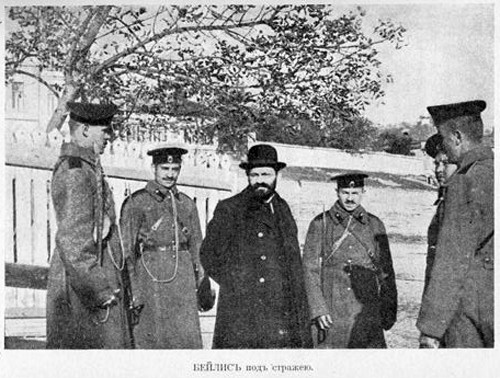

In 1913, in the most sensational trial of its kind until then, Menachem Mendel Beilis, a 39-year-old Jewish factory manager in Kiev, went on trial for ritual murder, a crime dredged from the twisted fantasies of Russian reactionaries. An international cause celebre, the trial confirmed once and for all that Czar Nicholas II’s autocratic regime was a bastion of deep-seated antisemitism.

Robert Weinberg, in Blood Libel in Late Imperial Russia (Indiana University Press), skillfully reconstructs the events that led to this appalling miscarriage of justice.

It all began on a Sunday morning on March 20, 1911 when the blood-soaked body of a 13-year-old boy, Andrei Iushchinskii, was found by a group of children playing in Kiev’s Lukianovka district.

Police investigators suspected his parents of the killing, having learned that his mother, a petty thief, and his stepfather had abused him. Right-wing groups in Kiev seized on the incident, falsely claiming that it was a ritual murder perpetrated by Jews and circulating an inflammatory flyer intended to whip up hysteria and hatred.

The myth of ritual murder, turning on the outlandish assertion that Jews need the blood of Christians to bake unleavened bread, emerged in 12th century Britain and spread to the European continent.

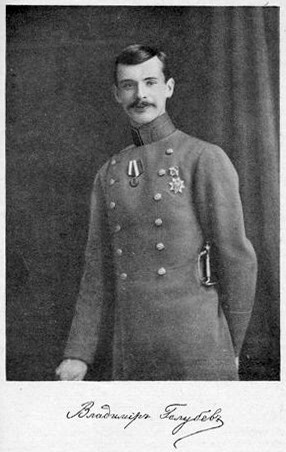

Vladimir Golubev, a Kiev University student whose father was a teacher at a Russian Orthodox seminary, called on the local prosecutor’s office to treat the case as a ritual murder. The authorities acceded to Golubev’s request, and in July of that year, Beilis was arrested and detained.

By the early 20th century, Kiev — the historic cradle of Christianity in Russia — was home to 58,000 of the more than five million Jews living in the Russian empire.

Anti-Jewish riots had rocked Kiev in 1881 and 1905, but had not erupted after Beilis’ arrest. This was odd, since Kiev’s city council was a nest of the antisemitic Union of the Russian People, known as the Black Hundred.

An autopsy found no evidence that the boy’s killer had drained his blood, but antisemites persisted in their campaign to frame Beilis. A second autopsy reached an identical conclusion, but that didn’t deter them either.

Liberal and progressive forces rallied behind Beilis, but the antisemites prevailed. In January 1912, the government officially indicted Beilis, despite protests from police and judicial officials that there was a lack of credible evidence. Indeed, the assistant police chief urged the government to focus on the boy’s mother as the real culprit.

The trial began on Sept. 25, 1913 and ended 34 days later.

Beilis was defended by Oskar Gruzenberg, a renowned Jewish criminal lawyer. He was assisted by a team of non-Jewish lawyers. The prosecutors were known antisemites.

Weinberg says that the case against Beilis was built on a foundation of “false testimony, flights of fancy and willful rejection of the truth,” while the trial itself was “a comedy of errors.”

The jury reached a verdict on two counts. The murder bore the hallmarks of a ritual murder, the jury announced in a 7-5 decision, but it was split evenly on the issue of Beilis’ involvement. “Under Russian law, a tied vote went in favor of the defendant, and so Beilis was a free man,” writes Weinberg.

While Beilis was exonerated, the antisemitic accusation against him was not laid to rest. “The jury’s decision that the killing resembled a ritual murder was significant,” Weinberg says. “Even though Beilis was not held responsible, the government`s strategy of demonstrating that a ritual murder had occurred had worked.”

In a demonstrable gesture of appreciation for their services, the government rewarded the prosecutors handsomely. But as Weinberg points out, the trial exposed the czarist regime, highlighting its harsh treatment of Jews and its utter contempt for the rule of law.

Beilis, a liberated but chastened man, left Russia after the trial, first settling in Palestine and then in the United States, where he worked as a printer and a salesman without much success. He wrote his memoirs, The Story of My Sufferings, which appeared in Yiddish and English. He died in 1934 at the age of 70, his funeral attracting several thousand mourners.

The minister of justice who had orchestrated the case was executed by the Bolsheviks. Golubev, the student who had led the charge against Beilis, died in battle during World War I.

Disturbingly enough, the grave of Andrei Iushchinskii has become a pilgrimage site for nationalists and antisemites, who view him as a martyr and a victim of a Jewish conspiracy to destroy Russian and Ukrainian culture and society.

More than a century after Beilis was wrongfully convicted of a crime he did not commit, the antisemites are still crying foul.