Bolesław Prus, a central figure in Polish literature and journalism in the second half of the 19th century and the first years of the last century, was drawn into the complexity of the “Jewish question” in Congress Poland, or the Kingdom of Poland. In his essays and novels, he addressed this issue fleetingly or in detail.

Prus (1847-1912), whose real name was Aleksander Glowacki, had an ambivalent attitude toward Polish Jews, leading observers to speculate whether he was a philosemite or an antisemite.

In what is described as the first book-length work to address this topic, Polish scholar Agnieszka Friedrich examines it in Boleslaw Prus and the Jews (Academic Studies Press), which was originally published in Polish.

Friedrich, a lecturer at the University of Gdansk, states that his position on Jewish issues changed over time. She cites the Polish historian Alina Cala as a reference. According to Cala, a specialist in Polish-Jewish affairs, Prus was favorably disposed toward Jews until the late 1880s. In keeping with the temper of the times, he moved into an antisemitic mode, portraying Jews as “the enemy of the Polish nation” in his novel Children.

As Friedrich observes, Prus was acutely conscious of the peculiar “love-hate relationship” between Poles and Jews. She explains it this way: “Aversion and an inclination to encumber Jews with all possible deficiencies are woven into an unbreakable knot with the awareness that they are useful, or even indispensable …”

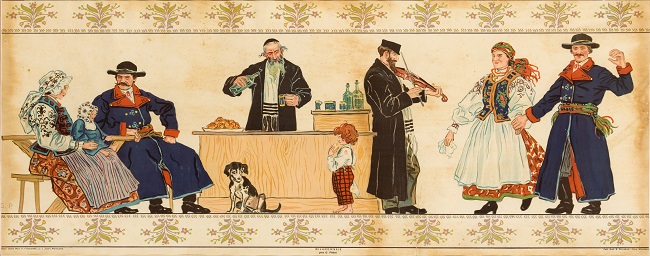

Prus condemned the “religious fanaticism” of Orthodox Jews, even as he acknowledged the virtues of the Talmud and accepted their distinct clothing. In the 1870s, he wrote, “Much has been written about Jews and their dress (and) sidelocks … As for me, I am happiest to leave that to them and would advise others to do the same.”

He had contempt for Yiddish, branding it as a “disfigured German patois” and a “foreign vernacular.”

He was an ardent advocate of Jewish assimilation, calling it “a natural and essential process that a healthy human soul cannot resist.” For Prus, an assimilated Jew could join Polish society, while an unassimilated Jew had “to adapt to Polish requirements.”

His belief in the assimilation of Jews was connected to a conviction that Jews and Poles were joined by an “organic bond.” He rejected the notion that Polish Jews constituted a nation within a nation and believed that they were a part of the greater whole of Poland.

He condemned antisemitism as an affliction, yet in 1910 he published a newspaper piece containing anti-Jewish rhetoric. While he praised assimilated Jews as “granules of gold and precious stones,” he claimed that the Jewish masses were alien to Poland and that some Jews were spreading “horrendous depravity” in their roles as “usurious pimps, retainers of brothels, thieves, acquirers of stolen items, organizers of bands of robbers and bandits, money counterfeiters (and) dishonest traders …”

Strangely enough, he played down the antisemitic aspect of the Dreyfus affair. “One might even get the impression that he deliberately turned a blind eye to it,” writes Friedrich.

Prus supported the Zionist movement’s objective of statehood as “noble” and “praiseworthy” and urged Jews “to regain your age-old homeland.”

In summarizing Prus’ dual attitude to Jews, Friedrich points out that he never called for anti-Jewish laws or restrictions, and claims that he “never incited racial hatred.” But as she herself noted earlier, his belief that Jews were spreading “depravity” is surely a form of antisemitism.

It would seem that Prus could only embrace assimilated Jews who had strayed from their traditions and customs, and that he looked down on the majority of Polish Jews with hostility, if not contempt.