Should the Allies have bombed the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland and the railway tracks leading to it? This is one of the most burning moral questions of the 20th century, and it’s examined in some depth in Bombing Auschwitz, a taut and absorbing documentary by Tim Dunn due to be broadcast by the PBS network on Tuesday, January 21 at 9 p.m. (check local listings).

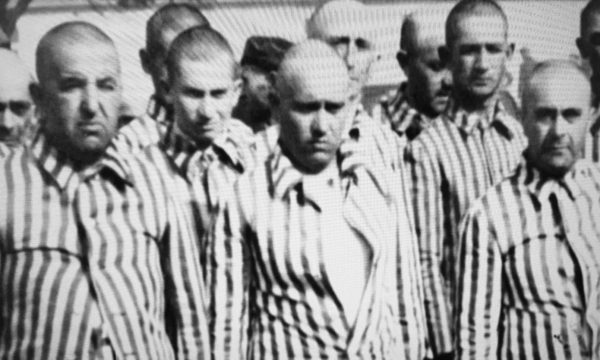

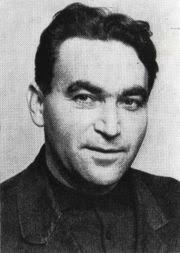

This question arose after two Jewish prisoners miraculously escaped from the camp in April 1944 and let it be known that Nazi Germany was preparing the gas chambers and crematoria of Auschwitz for a massive influx of Jews from Hungary. Nearly one million European Jews already had been murdered there when Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler made their daring escape, and now the Nazi commanders of Auschwitz were waiting to kill a further 400,000 Hungarian Jews expected to arrive in May.

The genocide of Hungarian Jewry was set into motion with Germany’s occupation of Hungary in March 1944. Within two months of the invasion, the Germans, in collaboration with Hungary’s fascist government, began deporting Jews to Auschwitz by train. These deportations started on May 15 and ended on July 9.

Vrba and Wetzler, Slovakian by nationality, were sent to Auschwitz in 1942, and there they witnessed the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews from countries ranging from Poland to Greece. Their knowledge of the camp and its killing facilities was second to none, and they were eager to share this damning information with the outside world.

The pair reached a safe house in neighboring Slovakia, where many Jews had already been murdered, and warned their Jewish interlocutors that Auschwitz was an extermination camp. By then, the Polish underground had acquired second-hand fragmentary data about Auschwitz thanks to Witold Pilecki, an officer of the Polish Army who escaped from the camp in April 1943. But Vrba and Wetzler were the first eyewitnesses to convey the full horror of it.

Their findings were contained in the Auschwitz Protocol, a detailed report that included drawings of the killing facilities. It was released on April 27, a little more than two weeks before the first transport of Hungarian Jews arrived in Auschwitz on their one-way journey of death.

Bombing Auschwitz, one hour in length, skillfully reconstructs by various means the events that transpired in the wake of their escape: dramatizations in which two British actors portray the escapees, interviews with survivors and historians, and World War II file footage. What’s missing is an interview with either Vrba or Wetzler. Despite the glaring omission, this is a documentary well worth one’s time.

One of the first Jewish officials to read the report was Michael Weissmandl, a Slovakian rabbi who forwarded an incomplete version of it to Roswell McClelland, the representative of the War Refugee Board in neutral Switzerland. The WRB had been established earlier that year by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to rescue and assist Jews in Nazi-occupied countries. Weissmandl, having urged the Allies to bomb Auschwitz, asked McClelland to pass it on to WRB’s head office in Washington, D.C.

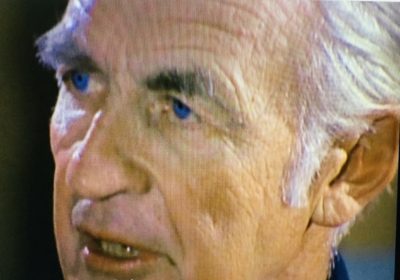

John Pehle, the WRB’s director, sent the report to John McCloy, the assistant secretary of war, in June. By this point, 55,000 Hungarian Jews were being murdered per week and the Holocaust had reached its frenzied climax.

The report reached British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden around this juncture. Two senior officials from the Jewish Agency in Palestine, Chaim Weizmann and Moshe Shertok, pleaded with Eden to bomb Auschwitz. He was initially receptive to their plea, as was his boss, Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Since the release of the Auschwitz Protocols coincided with Allied plans to invade France, held by Germany, the commander of the Royal Air Force was loathe to divert aircraft to bomb Auschwitz. As the film suggests, this was an unconvincing argument.

The Allies, having acquired air supremacy in 1944, were hitting targets in the vicinity of Auschwitz. The I.G. Farben plant, which manufactured synthetic oil for the German war effort, was bombed. And remarkably enough, Auschwitz itself was unintentionally hit, causing the deaths of 40 Jewish prisoners and 15 SS officers.

Jewish leaders in the United States, meanwhile, launched a campaign, spearheaded by Rabbi Stephen Wise, to persuade the Roosevelt administration to bomb Auschwitz. They were waging an uphill battle. U.S. officials from McCloy on down claimed that bombing Auschwitz would be militarily unfeasible and a diversion from the overarching objective of defeating Nazi Germany. Some opponents argued that many Jewish prisoners would be accidentally killed. In fact, Jewish inmates in Auschwitz would have welcomed an Allied air raid despite collateral damage, says one of the Holocaust survivors.

Two of the historians who appear in the documentary claim that the Allies’ reluctance to bomb Auschwitz was a moral failure. Another historian ascribes their position to antisemitism, which was deeply embedded in American society in the 1930s and 1940s.

Pehle, having read the full report some months later, disputed McCloy’s assessment. In November, he leaked the Auschwitz Protocol to the media. The story got so much attention that the Nazis destroyed Auschwitz’s four gas chambers.

Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945, by which point it had claimed more than one million victims. Years later, Pehle said in sorrow, “It’s tragic we didn’t bomb Auschwitz.”

Exactly.