Despite her status as one of America’s greatest movie critics, Pauline Kael was regarded as a persona non-grata by certain Hollywood movers and shakers.

Diverging from mainstream tastes, she would pan popularly acclaimed films such as The Sound of Music, Lawrence of Arabia and West Side Story, thereby enraging high-powered film executives, who barred her from some press screenings. In another instance, she was sacked from a mass-circulation magazine, whose editor expected conventional appraisals of movies.

These are among the nuggets a viewer gleans from Rob Garver’s one-and-a-half hour documentary, What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael, which opens in Toronto at the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on Friday, January 17.

Garver’s absorbing biopic takes us from Kael’s birthplace on a chicken farm in Petaluma, California, to her final years in New York City, where she died in September 2001, just eight days short of the Arab terrorist attack on the World Trade Center.

Born in 1919, the daughter of Polish Jewish immigrants, Kael studied philosophy, literature and art at the University of California in Berkeley, but dropped out before she could acquire a degree. She and her boyfriend, a poet, migrated to Manhattan and lived like bohemians. Kael worked as a nanny on Park Avenue and wrote copy for an advertising agency. These were not pleasant experiences, she recalls.

Soon enough, she was a single mother, a predicament that emboldened her to make something of herself, her daughter, Gina James, says in an interview.

Feisty, energetic, intellectually-inclined and endowed with a phenomenal memory, Kael wrote her first review for City Lights, a minor magazine in California. She composed her reviews in longhand, never having learned to use a typewriter. It was a hand-to-mouth existence. “We were very short on money,” James recalls.

During her formative years as a critic, Kael tried to loosen her ponderous academic style, being opposed to the “snobbish” art house film school of criticism.

She wrote her first book, I Lost It At the Movies, the first of 13, in the mid-1960s, and it was a commercial success. One of her last books, Deeper into the Movies, won the National Book Award in the early 1970s.

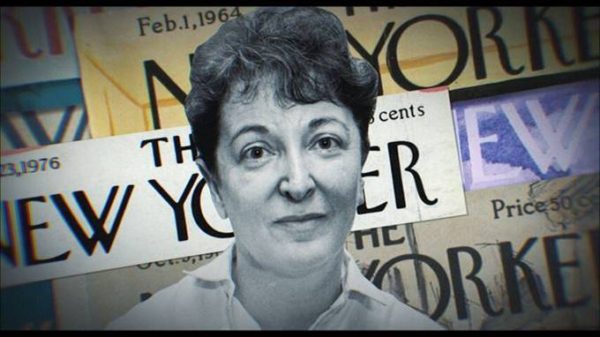

McCall’s, a major magazine, hired her as its film critic, but Kael’s tendency to lambaste popular movies cost Kael her job. As Garver says, she had the greatest “bullshit detector” in the industry. Kael moved to The New Republic, but disenchantment set in. Her reviews were rewritten without her permission, and a glowing review of Bonnie and Clyde she submitted was rejected.

William Shawn, the legendary editor of The New Yorker, admired her style and approach to movies and offered Kael a position as a critic. She would hold it from 1968 until her retirement in 1991. Yet even there, she could barely earn a living wage, James says.

Throughout much of her career, Kael was enormously influential. By Garver’s estimate, she “discovered” Brian de Palma, Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese. Kael, however, disliked Shoah, Claude Lanzmann’s much-applauded epic about the Holocaust, finding it exhausting. Kael’s critique prompted some to accuse her of being a self-hating Jew, a flimsy accusation at best.

Despite such barbs, Kael was widely appreciated in the film community.

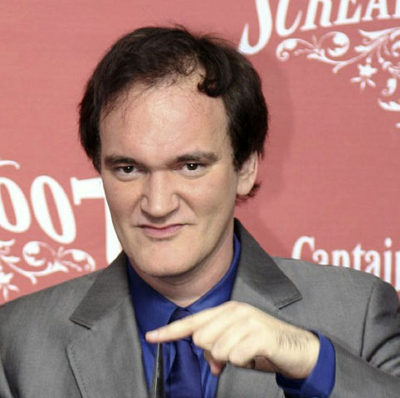

“We grew up reading Pauline Kael,” says filmmaker Quentin Tarantino in a succinct tribute of the clout she wielded. The film director John Boorman believes she influenced other critics.

Bottom line: She was a one-of-a-kind critic.