Vilified and idolized, William Randolph Hearst was the first media mogul in the United States, a larger-than-life figure brimming with arrogance and hubris whose appetite for power was limitless.

A man who prized innovation and was always in search of the next big thing, he accumulated an empire of daily newspapers, magazines, radio stations and news serials. His dailies were published in every major city, and at one point one in four families read them.

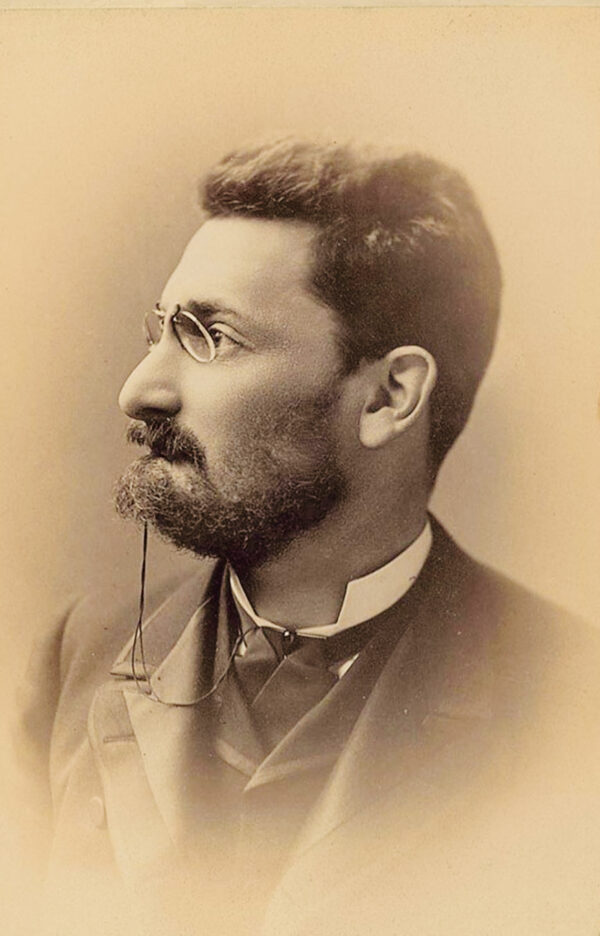

Like his Jewish rival, Joseph Pulitzer, Hearst flamboyantly changed the face of American newspapers by the bold use of layout, illustrations and color. But given to sensationalist yellow journalism, his concern for the truth was sometimes only skin deep.

Hearst is the subject of a bracing two-part series, Citizen Hearst: An American Experience Special, which will be broadcast by the PBS network on September 27 and 28 between 9 p.m. and 11 p.m. (check local listings).

The influence he wielded from the late 19th century until his death in 1951 was such that the film director Orson Welles was inspired to make a film about a fictional character loosely based on Hearst. Citizen Kane, released in 1941, is now a classic of the American cinema. But since Hearst hated it, not one of his newspapers reviewed it.

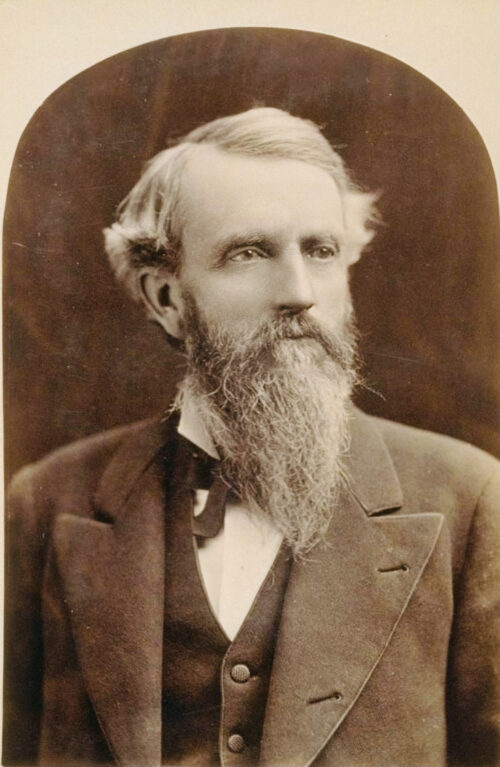

Born in 1863, he was the son of George Hearst, a millionaire who owned gold and silver mines. At Harvard University, he was the business editor of a student magazine, The Harvard Lampoon, whose circulation and revenues he increased by a substantial margin. Expelled from Harvard, he took over the reins of his father’s newspaper, The San Francisco Examiner, at the age of 24. He had bought it to further his political ambitions as a U.S. senator from California.

Hearst was a good boss, giving his reporters a lot of latitude and leeway if they followed his rules of conduct to the letter. The newspapers of his day were as dull as dishwater in terms of appearance. Hearst, known as The Chief to his employees, pumped verve and vitality into the Examiner, turning it into a punchy, lurid and irreverent daily. Within two years, the readership jumped from 5,000 to 50,000.

A white supremacist in an era when racism was extremely common, Hearst was fiercely anti-Asian, supporting the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act. Critics accused him of fanning the flames of racial animosity, but Hearst justified his views on the grounds of “race preservation.”

With his death in 1891, George Hearst left his wife, Phoebe, an inheritance of some $20 million, the equivalent of $500 million today. Being close to her son, Phoebe helped Hearst buy The Morning Journal, a New York daily with a circulation of 70,000. One of many dailies in the city, it was puny compared to The World, Pulitzer’s flagship newspaper with a readership of 250,000.

Determined to unseat Pulitzer as the city’s leading publisher, he poached his top reporters and editors and dropped the price of the paper from two cents to one cent. Soon enough, the circulation of The Morning Journal more than doubled to 170,000.

Like The World, The Morning Journal was mostly read by immigrants and fancied itself as a champion of working-class Americans. Hearst carried a disproportionate number of crime stories and railed against the corrupt trusts, the wealthy companies that gouged consumers. But at the same time, he underpaid the newsboys who distributed his newspaper, and he dehumanized African Americans in his comics.

Lambasting Spanish colonial rule in Cuba, The Morning Journal printed outright lies about conditions on the Caribbean island. Following the still mysterious destruction of the battleship U.S.S Maine in 1898, Hearst whipped up a frenzy of anti-Spanish fervor in manufactured news and drove the president to declare war on Spain. By then, The Morning Journal had surpassed The World as New York’s biggest daily.

Incredibly restless and ambitious, Hearst successfully ran for a seat in the U.S. Congress before deciding to seek the mayoralty of New York, a contest he lost thanks to Tammany Hall shenanigans. In the meantime, he purchased two newspapers in Chicago and married the chorus girl Millicent Willson, who would give birth to his five sons.

In 1909, he bought yet more newspapers in Los Angeles, Denver and Atlanta and founded a string of magazines ranging from Town & Country to Cosmopolitan. His media machine was financed by borrowed money from his mother, the most important person in his life. In nearly all cases, she forgave the loans. With Phoebe’s passing in 1919, he lost a mother but gained a fortune.

Awash in dollars and oblivious to costs, Hearst hired the architect Julia Morgan to build a fabulous castle complex at San Simeon, a working cattle ranch north of Los Angeles his father had bought.

He placed his collection of paintings, sculptures, Moorish columns, pottery, tapestries, carpets and antiques at San Simeon, which became one of his residences and the venue of parties that attracted guests from movie stars to intellectuals.

Hearst met the love of his life, the actress Marion Davies, in the early 1920s. She was the star of his silent film, When Knighthood Was In Flower, the most expensive movie to date. Smitten by Davies from the moment he met the blonde bombshell, she became his mistress and muse, much to the indignation of his wife. He advanced Davies’ film career, which flourished for a while despite her stutter, but which sputtered and died after a few box office bombs.

Although he initially backed President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda of progressive legislation, he denigrated it as the Raw Deal after a falling out with him. Hearst portrayed himself as a supporter of the working class, but he hypocritically opposed unionization efforts in his company.

As he grew older, he became more conservative, more dogmatic and increasingly anti-communist. He met Adolf Hitler, Germany’s new chancellor, in 1934, but raised no public objection to his antisemitic Nazi regime.

Hearst’s right-wing views alienated some of his readers, who stopped buying his newspapers and magazines. He lost millions of dollars and fell into debt, forcing him to cede control to trustees.

Politically, Hearst was a staunch isolationist. While he believed the United States should not embroil itself in European intrigues, he claimed that Japan posed a threat to American interests. During World War II, he called for the internment of Japanese Americans.

The war saved Hearst. Circulation increased and newsprint costs dropped, enabling Hearst to reclaim his empire.

He secretly gave Davies a controlling share in his company, but after Hearst’s death in 1951 at the age of 88, she sold it back to his wife for the princely sum of $1.

Citizen Hearst is a lively and fascinating account of a unique American entrepreneur. His innovative ideas and notions revolutionized journalism in the United States, but his disregard for balance in news coverage and his disdain for the absolute truth in storytelling remain dark legacies.