Coffee, perhaps the most common word on the planet, is a lucrative cash crop that provides employment for more than 25 million people in over 7o countries. Originally gathered from wild plants in Ethiopia in the 15th century, it was first cultivated commercially in Yemen, its supply strictly controlled by a clique of Arab merchants who called the product gahwah, the wine of Islam.

But as coffee plantations sprouted in tropical countries like Indonesia, Brazil, Cuba and Haiti, and as international trade expanded exponentially, the Arab monopoly was irretrievably broken and coffee morphed into the most valuable agricultural crop in the world’s poorest regions.

A useful stimulant and a source of instant energy, coffee was a luxury for society’s privileged classes until 200 years ago. But today it is a mass beverage and an unrivalled work drug, consumed by billions of people. By one estimate, nearly two-thirds of Americans drink at least one cup a day.

For the past 150 years, coffee has become an exceptionally valuable commodity in global capitalism, despite its boom and bust pricing cycles. Exports are now worth some $25 billion annually, and retail sales in shops and cafes are even higher.

The cultivation of coffee took hold in 18th century Latin America, where there was “sufficient sun, rain and forced labor to make it pay,” writes Augustine Sedgewick in Coffeeland: One Man’s Dark Empire And The Making Of Our Favorite Drug (Penguin Press), an impressive work of scholarship.

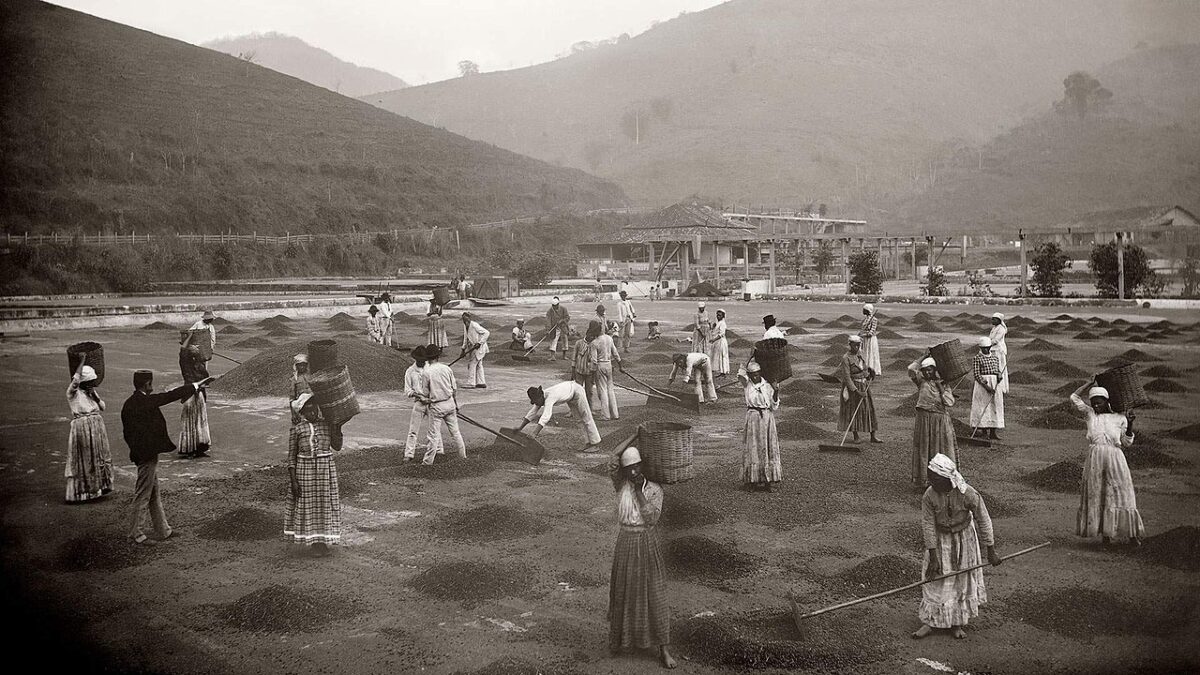

By the middle of the 19th century, Brazil produced half the world’s supply of coffee, which was planted, nurtured and harvested by an army of enslaved laborers. By the turn of the 20th century, Latin America was “the unchallenged global center of coffee production,” says Sedgewick, a City of New York scholar specializing in the history of food, work and capitalism.

El Salvador, the focus of his erudite and lucidly-written book, came relatively late to coffee. Until the 1840s, commercial agriculture in El Salvador — the smallest country in Central America — centered on indigo, which enlivened cotton goods.

“Compared with indigo, coffee was a temperamental and expensive crop, requiring abundant rain on a consistent schedule, enough sun to keep frosts at bay, and plenty of labor,” says Sedgewick. “Even under the best conditions, coffee trees yield mature harvests only after four to seven years of attentive cultivation.”

Furthermore, arable land in El Salvador was scarce, with one-quarter of it already farmed by Indian and peasant subsistence farmers.

In spite these problems, the El Salvadoran government persisted, its appetite whetted by the prospect of collecting export taxes and developing the economy. Having taken note of the profits generated by coffee plantations in neighboring states like Guatemala, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, El Salvador distributed free land to those who agreed to grow coffee, offered tax breaks to planters who had more than 5,000 trees, and exempted plantation workers from military service.

The state-led campaign promoting the cultivation of coffee focused on the northern highlands around the fertile Santa Ana volcano. By the 1860s, more than three million coffee trees had been planted in and around Santa Ana — the nation’s second-largest city — and El Salvador had been converted into a major hub of the coffee trade. The Santa Ana region would become a beehive of activity, with more than 500 producers and some 20 mills churning out tons of coffee per year.

Three decades later, in 1889 to be exact, an 18-year-old working-class youth from Manchester, James Hill, arrived in El Salvador. Starting out as a travelling textile salesman, he segued into coffee after marrying Maria Delores Bernal, the daughter of a successful local planter. “From this unlikely beginning,” as Sedgewick notes, he built a coffee empire his neighbors and rivals considered the finest in El Salvador and, therefore, the world.

By the 1920s, he was widely regarded as the “king of coffee.” At his death in 1951, he ruled an archipelago of 18 plantations on 3,000 acres that employed 5,000 workers at the height of the season. Hill’s mill, Las Tres Puertas, produced about 2,000 tons of export-ready coffee beans in a good year. His children inherited J. Hill Coffee Company after he died.

According to Sedgewick, Hill — an innovator who refined the Bourbon and peaberry varieties of Arabica coffee — did more than anyone else to transform his adopted country “into one of the most intensive monocultures in modern history. By the second half of the 20th century, due in part to practices Hill introduced on his plantations and in his coffee mill, coffee covered a quarter of El Salvador’s arable land and employed a fifth of its population.”

In time, coffee accounted for more than 90 percent of its exports and a quarter of its gross domestic product. But as Sedgewick points out, there was a dark side to coffee. As the owners of bigger plantations acquired still more land, they dislodged peasants from their ancestral holdings, and the end result was disastrous.

Coffee trees not only supplanted citrus, mango and yucca orchards, but uprooted vegetable gardens and maize, rice and bean fields, spreading hunger and misery. “The conquest of territory by the coffee industry is alarming,” Sedgewick quotes one 19th century observer as saying.

The gap between the very rich and the very poor widened tremendously and was such that, by the early 20th century, 80 percent of the children in El Salvador were malnourished, while a small number of extraordinarily wealthy families, including the Hills, achieved a near monopoly over the country’s land, resources, economy and politics.

“Thirty or 40 families own nearly everything in the country,” a U.S. military attache wrote in the 1930s. “They live in almost regal style with many attendants, send their children to Europe or the United States to be educated, and spend money lavishly … I imagine the situation in El Salvador today is very much like France was before its revolution (and) Russia was before its revolution.”

Hill used food rather than wages to attract laborers, offering them a free breakfast of tortillas and beans. And being more enlightened, if not more pragmatic, than some of his myopic and callous contemporaries, he insisted that all food served would be clean and healthful.

“He discouraged direct physical violence as a strategy of labor management on his plantations, and he specifically sought to hire managers who would not be rough with the people under their charge,” adds Sedgewick.

Yet coffee planters were not loathe to deploy violence against workers who sought better conditions and against so-called “outside agitators” who worked on their behalf.

Coffee played an integral role in generating wealth and creating the phenomenon of globalization, but in El Salvador, in particular, it exacted a heavy human price, as Sedgewick emphasizes in his highly readable book.