Until my first visit to Israel shortly after the Six Day War, I knew absolutely nothing about the magnificence of Middle Eastern cuisine.

Raised on a steady diet of Jewish-style Polish food, lovingly cooked and baked to perfection by my mother, Genia, I could look forward to such simple and tasty dishes as lima bean-and-onion dip, kreplach, sauerkraut-and-potato soup, kugel, meatballs in tomato sauce, candied turkey legs and apple cake.

I expanded my gastronomic horizons after visiting Israel in the summer of 1967. Living and working on a kibbutz near Netanya, and travelling around the country, I discovered the delights of hummus, felafel, pita bread, tabbouleh, olives and the array of wonderful local spices and herbs that can enliven practically any meal.

Several years later, having met the amazing Bulgarian-born, Israeli woman who would become my wife and the mother of my lovely two daughters, my knowledge of Israel’s culinary scene grew exponentially. I learned to love bourekas, stuffed vegetables, and a scrumptious dessert from the Balkans known as Creme Bavaria, whipped up effortlessly by my solicitous mother-in-law, Rene Lazarov of Jaffa.

Bless her soul, Rene also introduced me to Turkish coffee, which I still faithfully drink every morning with my breakfast of a sliced pumpernickel roll slathered with a generous and rotating coating of ajvar, peanut butter, jam, cheese or herring.

Israeli food, of course, is derivative, having been shaped by waves of immigrants from every corner of the globe. But I would argue that the Palestinians have exerted the greatest influence on it.

There are 12 million Palestinians around the world, concentrated in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and several neighboring Arab countries. Two million Israeli citizens of Palestinian descent live in Israel. Their culinary traditions having seeped deeply into Israeli society. Palestinian food is ubiquitous and Palestinian restaurants are increasingly popular. One of my favorite ones, Abu Hassan in Jaffa, serves excellent hummus.

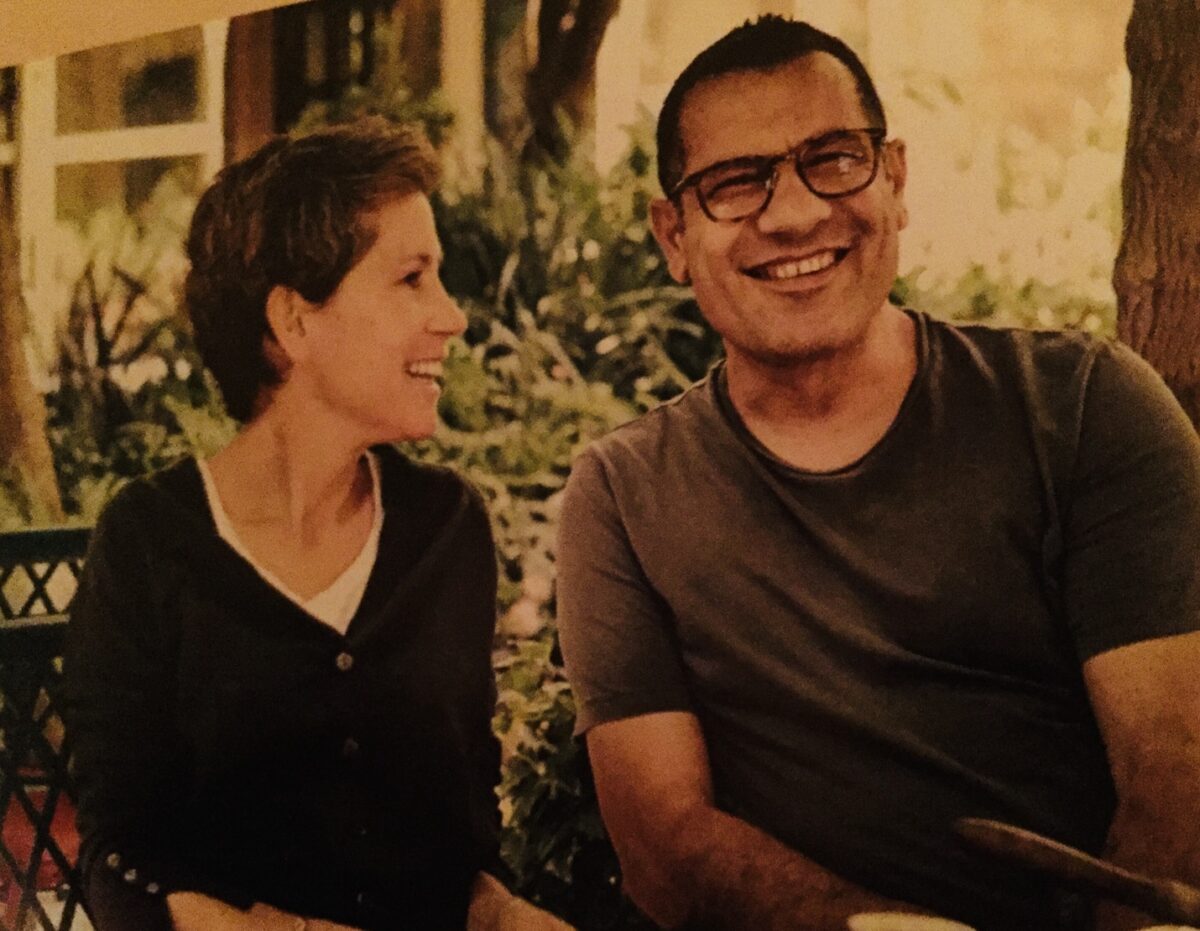

Falastin, a lavishly-illustrated coffee-table volume co-written by Sami Tamimi and Tara Wigley and published by Appetite, an imprint of Penguin Random House, showcases the range and depth of Palestinian fare. “This is a book about Palestine — its food, its produce, its history, its future,” they write.

Tamimi, a Palestinian chef from East Jerusalem, learned his trade in Tel Aviv and has lived in London for the past two decades. He and an Israeli food maven, Yotam Ottolenghi, run a chain of restaurants and have written a series of cookbooks, most notably Jerusalem and Ottolenghi Simple. Wigley, a graduate of a cooking school in Ireland, has worked with Tamimi and Ottolenghi since 2010.

“In Falastin, Tara and Sami have picked up the baton where it was a left after Jerusalem,” Ottolenghi writes in the foreword. “Once again, this is a purely delicious affair … It is based on Sami’s childhood in Palestine and Tara’s journey into the universe of tahini, zaatar and precarious savory rice cakes (maqlubeh).”

There are 120 recipes in Falastin, covering appetizers, mains and sweets, and they’re brought to life by an array of sharp color photographs.

Shakshuka, a dish of scrambled eggs, crushed tomatoes, red peppers, feta cheese and spices, as well as three versions of hummus, are listed. Falafel is made with sumac and onions. Kubbeh, tightly packed balls of bulgar and ground meat, pairs exceedingly well with a finely chopped salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, onions, parsley, mint and a lemon dressing.

The braised fava bean dish, slathered with olive oil and lemon, is pungent and rich. The charred eggplant and lemon soup, topped with walnuts, looks divine. Bulgar mejadra, a seemingly humble concoction of lentils, chickpeas, bulgur or rice and crispy onions, is comfort food par excellence.

Lamb and beef kofta, tossed with tahini, potatoes and florets of cauliflower, is optically appealing, as is roasted cod with a cilantro crust.

The Palestinians’ national dish, chicken musakhan, explodes with an intoxicating mixture of cumin, sumac, cinnamon, allspice, black pepper, pine nuts, red onions, parsley leaves and flatbread.

Maftoul, a Palestinian favorite, is a melange of chicken legs or breasts, couscous, olive oil, butternut squash and spices. Sambousek, the Arabic version of Indian samosas, is filled to bursting with chickpeas, sirloin steak and a melange of spices.

If you’re an aficionado of bread, the Palestinian sesame bagel, fresh out of the oven, appears irresistible. It’s chewy and great as is, or as a platform for a sandwich.

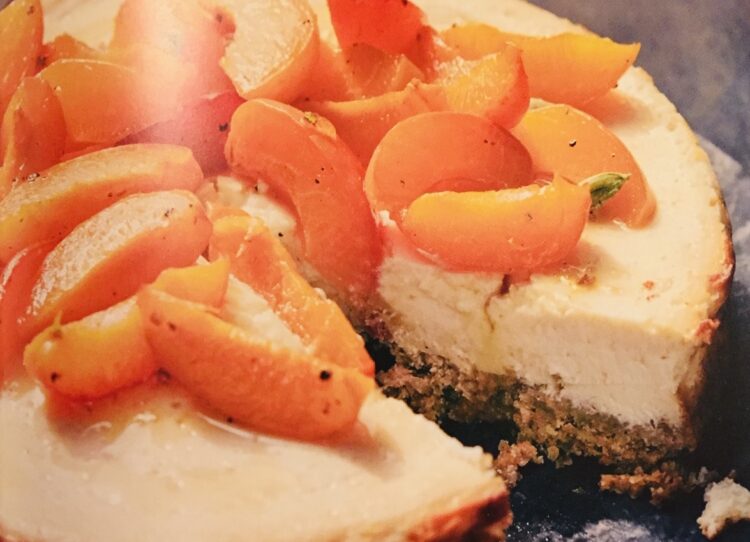

If you’re partial to dessert, you may well be drawn to knafeh, a warm, soft, sugar/syrup-drenched cheesy pastry, the finest of which are apparently produced in the West Bank town of Nablus. Alternatively, you can feast on labneh cheesecake, which is layered with roasted apricots, honey and cardamom.

Tamimi and Wigley deal, in the main, with Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. But they pause in Haifa and Nazareth, both of which are mixed Jewish-Arab cities in Israel. In Haifa, near Mount Carmel, they drop in at the Lux, a restaurant owned by Alla Musa. In Nazareth, they stop at Daher Zeidani’s restaurant, where meals are served with “a very large side order of politics.”

The contentious and protracted Arab-Israeli conflict is a recurring theme throughout Falastin, as it must inevitably be.

A sub-chapter deals with the question of land ownership in Area C of the West Bank, which has fallen under Israel’s full control since the 1993 Oslo peace accord. As Tamimi and Wigley observe in understated style, “Area C contains most of the West Bank’s natural resources and open areas, but the distribution of these resources — most noticeably water and the freedom to build — is far from equal.”

Half of the farmed land in the West Bank is planted with olive trees, which produce succulent olives and superb olive oil. Some of these plots, which support ancient trees, have been uprooted to make way for the expansion of Israeli settlements, they note. Still others have been damaged by Jewish settlers.

The authors profess to understand why the United Nations granted Jews a homeland in Palestine in 1947. As they put it, “Starting a national state for a population who had been persecuted, killed and tortured over centuries was not just an understandable necessity; it was a global imperative. The big mistake, of course, was ignoring the rights of the Palestinians who were already living there.”

The 1917 Balfour Declaration is described in the same vein.

These are big, divisive issues better left to historians and politicians. Tamimi and Wigley touch on them in passing. But what they do best is to provide readers with a lucid and panoramic survey of the Palestinians’ wholesome and delectable cuisine.

Tahini, a paste fashioned out of roasted and pressed sesame seeds, is at the base of Mediterranean cooking. Creamy and nutty, it is one of the key ingredients of hummus, a popular Middle East snack.

Amy Zitelman’s book, The Tahini Table (Agate), is a celebration of this sublime paste in words and photographs. She and her sisters, the principals of Soom Foods in the United States, have promoted tahini tirelessly and effectively.

“The Zitelmans have done more than anyone to rescue tahini from the dusty back shelves of Middle Eastern groceries and present it to mainstream America as a healthy and delicious ingredient,” opines the celebrity chef Michael Solomonov in the foreword. “The quality of their tahini is without comparison.”

As Zitelman says, “The secret of great tahini is in the seed.” She imports hers from Ethiopia’s Humera region. Consistently buttery, they are the world’s most prized sesame seeds.

In this accessible book, she offers readers a panoply of mouth-watering recipes with the accent on tahini, from tahini barbecue sauce and cauliflower tahini spread to maple tahini granola to tahini sweet potatoes.

Yotam Ottolenghi is a big fan of vegetables. “I have never been shy of my love of vegetables,” he says in his newest book, Flavor (Appetite), which is co-written with Ixta Belfrage.”I have been singing the praises of cauliflowers, tomatoes, lemons and my old friend the mighty eggplant for over a decade.”

Still, he confesses, how many more ways are there to fry an eggplant, to slice a tomato and to squeeze a lemon? “The answer, I am delighted to report, is many.”

Ottolenghi has devised a sensible and foolproof method of maximizing the flavors and aromas of vegetables. And in this volume, he shows us how to do it with the help of ingredients like Aleppo chilis, anchovies, fish sauce, miso, mango pickle and tamarind paste.

The recipes are eclectic.

Chilled avocado soup with crunchy garlic oil. Sweet potato in tomato, lime and cardamom sauce. Israeli couscous and squash in tomato and star anise sauce. Asparagus salad with tamarind and lime. Spicy mushroom lasagne. Fried onion rings with buttermilk and turmeric. Spicy roast potatoes with tahini and soy.

With this innovative and addictive book in hand, vegetarianism emerges as a realistic and attainable option.