The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the most consequential American foreign policy decision of the 21st century, is scrutinized in minute detail by the historian Melvyn Leffler in Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq (Oxford University Press).

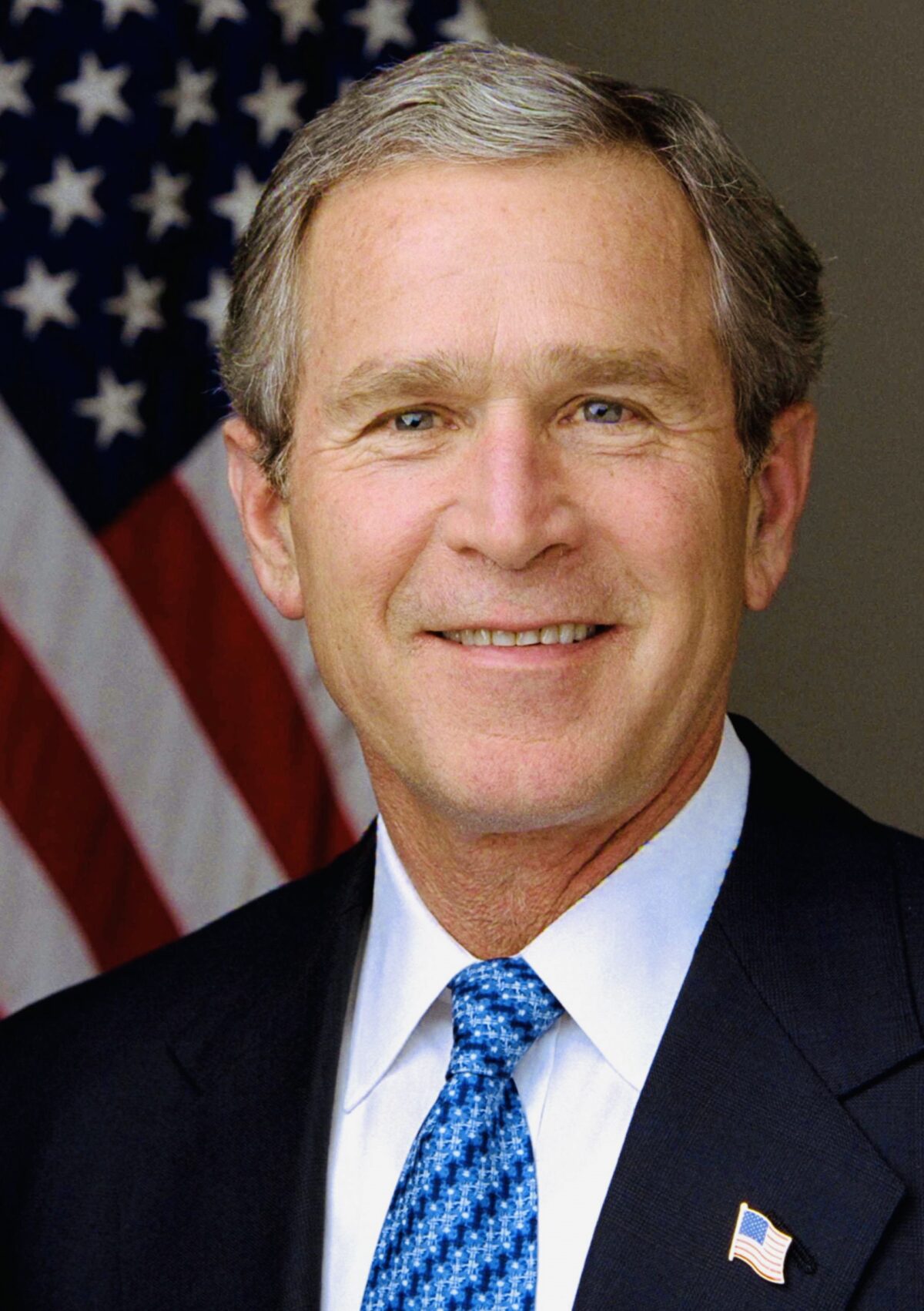

Leffler, an emeritus professor of American history at the University of Virginia, methodically examines why Bush decided to invade Iraq and why the second Gulf War in 12 years went awry so quickly and turned into a “tragedy.”

In Leffler’s considered opinion, the war was a fiasco from every conceivable angle.

Internally, it demoralized the American people and intensified partisan divisions. Externally, it aroused widespread anti-Americanism, alienated key allies, devastated the moral authority of the United States, and distracted attention from the challenges posed by the turmoil in Afghanistan and the rise of China.

And rather than concretely contributing to the overall war on terrorism, it complicated that struggle, fueling Muslim grievance and attracting new recruits to that cause, he adds in a somber analysis.

Leffler, in chapter one, introduces a reader to Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi dictator who sealed his fate and that of his nation with his foolhardy invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Iraq’s naked aggression triggered the first Gulf War in 1991 and sowed the conditions that prompted the U.S. to invade Iraq, which led to Saddam Hussein’s demise.

Born into an impoverished family in 1937, he was a tough and cunning operator whose burning ambition as a young man was to topple the Iraqi monarchy and the Sunni elite. His ascent in Iraqi politics was facilitated by his uncle, Khairallah, and his cousin, Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr, who would become the leader of the Ba’ath Party and the president of the Baathist regime in 1968.

Although he was not driven by strong ideological convictions, he sought to consolidate Ba’athist rule, modernize Iraq, reclaim its glorious past, suppress Shi’a and Kurdish opponents, contain Iran, unify the Arab world under his banner, and destroy Israel.

Pushing aside Bakr in a bloodless coup, he seized total control in the summer of 1979. Little more than a year later, he invaded Iran, Iraq’s regional rival, in what would be a futile war that cost the lives of 125,000 Iraqis and many more Iranians.

On the heels of that war, which ended inconclusively in 1988, he set his sights on Kuwait, which, territorially, had once been part of Iraq, and which was allied to the United States. Saddam’s adventure in Kuwait backfired badly, placing Iraq, a relatively underdeveloped Arab country, on a collision course with the world’s greatest superpower.

Fast forward to the new century.

In his State of the Union address to Congress on January 20, 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush focused on domestic issues like reforming the social welfare system and cutting taxes. But after Al Qaeda’s attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, which resulted in the deaths of 1,466 people in New York City alone, Bush’s priorities were completely upended.

By Leffler’s estimation, Al Qaeda’s leader, Osama bin Laden, was animated by grievances that resonated with many Arabs: contempt for U.S. hegemony in the Middle East, revulsion at the presence of U.S. troops stationed there, and a loathing for Israel.

Al Qaeda had not really been on the Bush administration’s radar until then, though an analyst on the staff of Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security advisor, had warned in a memorandum that it was a danger to U.S. interests in the Middle East. That prescient official, Richard Clarke, wrote that Al Qaeda sought to drive the U.S. out of the Muslim world and supplant friendly regimes with theocracies. Clarke also recommended that Al Qaeda’s sanctuary in Afghanistan, ruled by the Taliban, should no longer be tolerated.

Neither Rice nor Secretary of State Colin Powell shared Clarke’s appraisal. They were preoccupied with, among other issues, Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, and the tensions between India and Pakistan.

Iraq, though, loomed large as an issue. The Bush administration was focused on Iraq’s stockpile of weapons of mass destruction, the Iraqi threat to countries in the region like Israel, and the sanctions that had crippled Iraq’s economy.

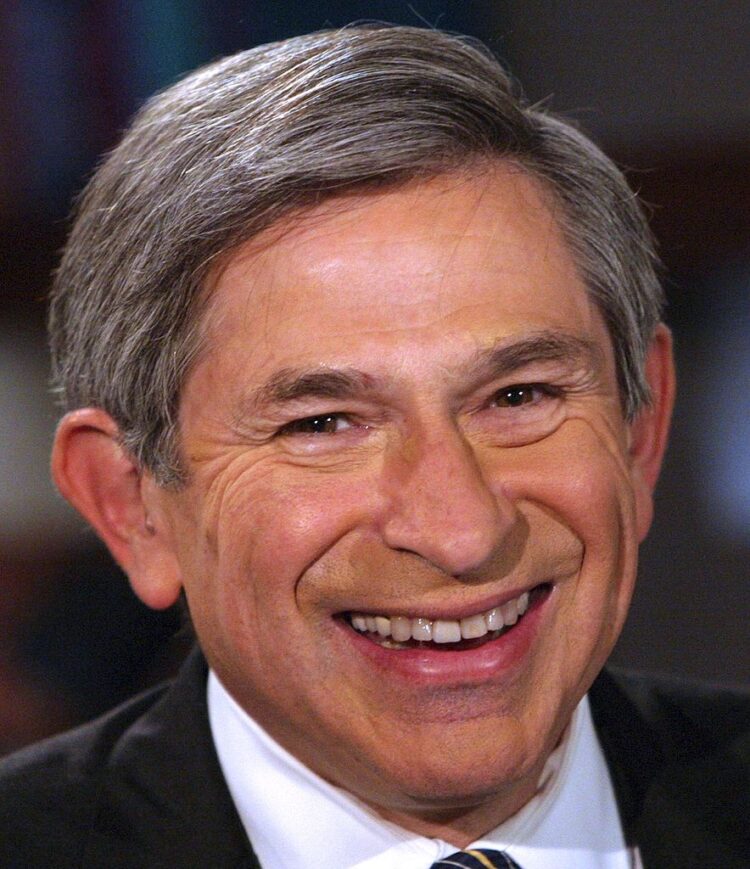

Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld’s deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, who hated Saddam as a repressive tyrant and who believed that he threatened U.S. interests, advocated a long-term policy to topple Saddam and usher in regime change. Rather than calling for an invasion, he wanted to arm the Iraqi opposition, enforce a safe haven in Shi’a-dominated southern Iraq, and recognize a provisional Iraqi government in areas outside Saddam’s control.

Bush, however, rejected suggestions that Iraq be attacked, contending that Saddam was not involved in 9/11. Bush, whose father had been the object of an Iraqi assassination attempt in 1993, received this information from George Tenet, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and Michael Morell, Bush’s daily intelligence briefer.

Bush was laser focused on Afghanistan and the global war on terrorism, which he framed as a civilizational battle against the forces of darkness rather than against Muslims per se. Neither Rumsfeld not Wolfowitz could convince Bush to pay greater attention to Iraq. He was fixated on Afghanistan and the broader war on terror.

Nonetheless, Bush was haunted by the specter that Iraq — the only Arab nation which had not condemned 9/11 — might be in possession of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons of mass destruction. Since the Central Intelligence Agency could not officially confirm this suspicion, Iraq was deemed to be a “gathering” rather than an “imminent” threat that could be contained. U.S. knowledge of Iraq, however, was based on imprecise intelligence and remained skimpy.

Cognizant of this significant contraint, Bush sought to intimidate Saddam by using the threat of force to achieve two objectives: to remove him from power and pressure him to allow United Nations monitors to resume the inspection of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. Bush was not certain whether he wanted to go to war in pursuit of these goals. Tenet and Vice-President Dick Cheney argued that only an invasion could remove Saddam.

In Leffler’s view, Saddam did not do much to allay U.S. fears. Iraq invested enormous funds in its military industrial complex and acquired dual-use items and materials that could be transferred to chemical and biological weapons. Iraq, too, financially supported the Palestinian cause.

With his State of the Union speech in 2002, during which he claimed that Iraq, Iran and North Korea constituted “an axis of evil,” Bush’s attitude toward Saddam hardened. And while his attention was deflected by the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising, he was certain that Saddam had to be ousted. Bush’s certitude was bolstered by British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who thought that Saddam was a looming threat and must be dealt with now.

In August of that year, Bush green lighted an invasion plan submitted to him by General Tommy Franks and began sending soldiers and equipment to the Middle East. Bush temporarily pressed the pause button after the Wall Street Journal published an article by Brent Scowcroft, who had been President George H.W. Bush’s national security advisor, advising against such a drastic move. Scowcroft claimed that an invasion would inflame the Middle East and alienate U.S. allies.

Chastened by Scowcroft’s warning, Bush resorted to a policy of “coercive diplomacy.” As Leffler explains, “The president hoped that (Saddam) would yield to the united pressure of the international community, and the buildup of U.S. forces would make that pressure credible.”

Bush told the United Nations that a war could be avoided if Iraq destroyed all its weapons of mass destruction and long-range missiles, agreed to United Nations inspections, ended all support for terrorism, and stopped circumventing economic sanctions.

Saddam underestimated Bush, believing he could outsmart the United States. He assumed Washington would not resort to force to topple him and counted on Russia and France to check Bush’s bellicose instincts. To assuage the West, he said he would permit United Nations inspectors to return to Iraq and reiterated his claim that he had no weapons of mass destruction.

Bush discounted Saddam’s public relations blitz, fearing he would share his weapons of mass destruction with terrorists.

In January 20o3, he told Rice that coercive diplomacy was not working and that Saddam had succeeded in concealing his weapons of mass destruction. By the end of that month, Bush had decided he had no alternative but to wage war, despite Iraq’s cooperation with the United Nations.

Leffler contends that the United States had no solid plan to govern Iraq after Saddam’s fall and was surprised by the ensuing chaos. While Bush announced the end of combat operations on May 1, anarchy prevailed in Iraq. U.S. military commanders there were completely unprepared for the lawlessness and disorder.

“The occupation intensified sectarian strife and insurrectionary activity in Iraq,” writes Leffler.

An already bad situation was exacerbated by two major U.S. decisions — the de-Ba’athification of Iraq and the disbandment of the Iraqi army, both of which threw thousands of Iraqis into the ranks of the unemployed and into the arms of insurrectionists waging guerrilla warfare.

The wave of terrorism made it all the more difficult for U.S. administrators to rebuild Iraq and revitalize its economy.

No weapons of mass destruction were ever unearthed, but Saddam was found hiding in a hole on a farm on December 13, 2003. He was hung three years later. Before his execution, he was interviewed extensively by an American interrogator. Saddam told him his aspirations were to thwart Iran, defeat Israel and dominate the Arab world.

In the wake of the invasion, the Islamic State organization emerged, taking over a significant swath of Iraq and Syria, and Iran’s power and influence increased dramatically.

The defanging of Iraq seemed like a sensible idea, but in practice it proved to be less than a wise course of action, as Leffler demonstrates in his illuminating book.