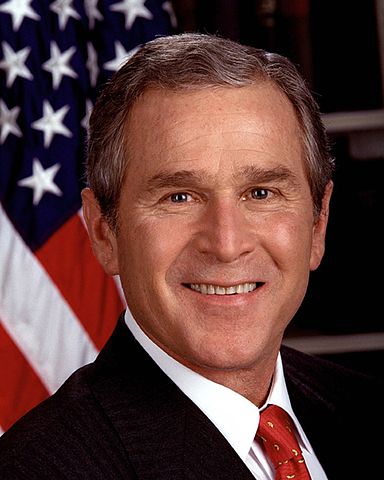

In the spring of 2001, George W. Bush, the then president of the United States, asked his friend, Robert W. Jordan, a Dallas lawyer, to be America’s 25th ambassador to Saudi Arabia, a major U.S. ally in the Middle East and an active participant in regional developments, its autocratic system of government and its intolerance of dissent and religious minorities notwithstanding.

Jordan arrived in Riyadh, the Saudi capital, in October, about a month after Arab hijackers crashed commercial airliners into the World Trade Center in Manhattan and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

It was an extremely sensitive moment in U.S.-Saudi relations.

Fifteen of the Arab terrorists who had wreaked havoc in the United States on September 11, 2001 were Saudi nationals. As the United States prepared to attack Afghanistan in punishment for 9/11, the Bush administration sought to enlist the Saudis in the war effort. The problem was that the ruling House of Saud fretted about the optics of allowing American aircraft to bomb a neighboring Muslim country from bases in Saudi Arabia.

Bilateral tensions increased after the Bush administration, having decided to invade Iraq, requested yet more military facilities from the Saudi authorities.

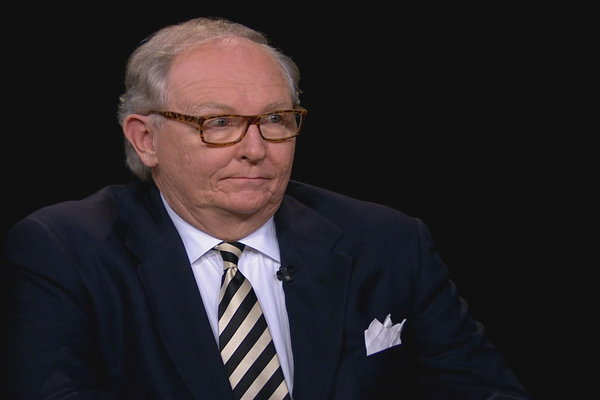

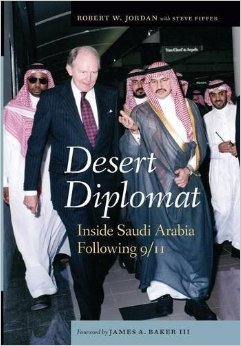

During this eventful two-year period, Jordan was the face of American diplomacy in the vast kingdom. What he experienced there is set out in his lucid and candid memoir, Desert Kingdom, published by the University of Nebraska Press.

Jordan is the first to acknowledge he was not a career diplomat when he accepted the posting. But, as he points out, the Saudis prefer U.S. envoys to be political appointees rather than foreign service officers. As he explains, “The Saudis want the ambassador to be a friend of the president who can get the White House on the phone at a moment’s notice.”

James Baker, the former U.S. secretary of state who contributes a brief essay to Desert Diplomat, believes Jordan was well suited to carry out his mission. “He was intelligent, savvy and street smart,” writes Baker in the foreword.

Although Jordan was inclined to accept Bush’s job offer, he had reservations about “the Saudi state’s view of women and Jews.” He left his doubts at the door, hoping he could use his powers of persuasion to nudge the Saudis into a better place.

Not long after his arrival in Riyadh, Jordan learned that his task in Saudi Arabia would be very challenging. “First, a number of senior Saudi royals were in utter denial that 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudis. Worse, a significant number of those hijackers had obtained their visas to enter the States legally, through our consular offices…” To make matters worse, he adds, U.S. officials were denied permission to interrogate Saudi terrorist suspects or even to examine their cell phones.

Jordan’s chief Saudi interlocutors were Crown Prince Abdullah, who eventually ascended to the throne, and Adel al-Jubeir, a diplomat who would be appointed foreign minister after having been ambassador to the United States.

“I frequently expressed to the crown prince my support for his reform agenda and began to press further on issues of human rights, religious freedom and women’s rights,” he says. “He was open to discussing these issues but clearly did not want to appear to be acceding to U.S. pressure to liberalize.”

One of the issues on Jordan’s radar revolved around Saudi Arabia’s propensity of turning a blind eye to local donors who supported extremist Muslim causes in the Arab world. “After more than a dozen years of seeking answers, there still has been no evidence directly linking high-level royals or officials to international funding of terrorists,” he claims.

This issue, however important, was eclipsed by Iraq.

On December 11, 2002, Jordan learned from Bush himself that the United States intended to depose the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein. “Bob, we’re fixin’ to do regime change in Iraq,” Bush said. The president expressed doubts that the Saudis would support a U.S. invasion, but Jordan soothed his fears. As he told Bush, “They might condemn us in public, but in private we would get assistance in using bases, logistics, border crossings and intelligence.”

Jordan was not entirely confident that diplomacy and sanctions had been fully exhausted before the United States struck Iraq in 2003, but he supported the war effort nonetheless.

Abdullah despised the Iraqi regime, but hoped that a war could be averted. The Saudis, he says, “hated Saddam and wanted him gone. But they were wary of creating a vacuum into which their mortal enemy, Iran, could move.”

As Jordan had predicted, the United States received Saudi assistance. “We got basically all we had seriously asked for,” he writes. “Questions have been raised about whether the Bush administration ‘sold out’ to the Saudis to secure their cooperation. I saw no evidence that we softened our positions on terrorism, human rights or religious freedom.”

During the leadup to the war, the Saudis demanded a quid pro quo from the United States — a commitment that the Arab-Israeli conflict would be resolved. “Their message was, ‘Look, if we’re going out on a limb to help you in Iraq, we need to show the Arab world, and especially our own people, that we are getting something in return on the Palestinian front.'”

There are several other references to the Arab-Israeli dispute in Desert Diplomat. Abdullah, in a meeting with Bush, warned him that Saudi Arabia would reevaluate its relationship with the United States unless it showed more leadership on the Palestinian issue. At another juncture, the Saudis expressed dissatisfaction with Washington’s “tepid” response to Israel’s siege of Yasser Arafat’s headquarters in Ramallah and of the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem. Nor were the Saudis pleased by Bush’s characterization of Ariel Sharon, the then Israeli prime minister, as a “man of peace.”

The Palestinian question, Jordan observes, was a “recurring theme and source of Saudi anger at me.” In the Saudi view, the United States should have no trouble resolving it. “All Washington had to do was to snap its fingers and Israel would come to heel, do whatever we commanded it to do.”

Jordan says the Saudis “went ballistic” when the United States neglected to show them an advance copy of the 2003 “road map” Arab-Israeli peace plan. “Adding fuel to the fire was the fact that Abdullah had offered his own peace plan in early 2002 and had received only tepid support from the United States,” he observes.

Jordan says the Saudi government never objected to American Jews working in the U.S. embassy or in the private sector. “A number of our embassy officials over the years were Jewish, including one very senior official who served after I departed. The Saudis reserved their antipathy for ‘Zionists,’ generally meaning the Israelis.”

Top-ranking Saudis treated Senator Joe Lieberman, an observant Jew, with the utmost respect when he visited the country on a fact-finding tour. At the royal palace, Abdullah personally led Lieberman through the buffet tables, “pointing out all the halal dishes, which are essentially kosher.”

During a trip to New York City, Jordan was invited to lunch at a fancy French restaurant by a wealthy Saudi businessman and an influential Saudi political advisor. A woman approached their table and began chatting with the advisor. She was Judith Miller, a New York Times reporter who would cover the war in Iraq. Miller said she was waiting for her party to arrive. Much to Jordan’s surprise, one of her guests was Shimon Peres, the former prime minister of Israel.

“Our two parties were fascinated by each other. We moved our chairs together and had a remarkable round-table discussion. The conversation was civil, thoughtful and provocative. It was clear to me that these Israelis and Arabs had much in common, including a desire to solve the problems that divided their constituencies.”

Jordan resigned in October 2003, exactly two years after having been appointed ambassador.

Ticking off a list of what he will miss and not miss in Saudi Arabia, Jordan says he will miss the desert and the food, among other things. But he will not miss (1) the rivalries and backbiting among the White House, State Department and Defence Department, (2) the dysfunctional Saudi government, (3) the Saudi intolerance of any religion other than Sunni Islam, (4) the textbooks that “denigrate Jews in coarse terms” and (5) the treatment of women.

Jordan, in closing, claims that Saudi Arabia’s greatest concern is Iran, its Shiite rival. In light of Iran’s fierce reaction to Saudi Arabia’s recent execution of 47 dissidents, including the Shiite preacher Nimr al-Nimr, Jordan’s assessment of their intense rivalry seems accurate enough.