Anthony Bourdain, the bestselling author and successful television host, hanged himself in a rustic hotel in Kaysersberg, France, on June 8, 2018 at the height of his fame. He was 61. At his death, he was in the midst of filming the latest episode of his immensely popular food and travel show, Parts Unknown, which was carried by CNN, the cable TV network.

Talented and charismatic, Bourdain seemed to have everything going for him. Yet beneath the veneer lay a troubled spirit who had been addicted to alcohol and drugs.

Charles Leerhsen, an American journalist, tracks the trajectory of his life and career in Down and Out in Paradise, a wide-ranging and sympathetic biography published by Simon & Schuster. Leerhsen’s book is based on two major sources: interviews with Bourdain’s friends and associates and his personal files.

Bourdain was the eldest son of Gladys Sacksman, a Jewish journalist, and Pierre Bourdain, a French salesman who rose to merchandising manager at Columbia Records. He identified as Jewish, but regarded himself as non-observant.

According to Leerhsen, he detested his mother, a New York Times editor who could be harsh, bossy, judgmental and difficult, but loved his father, a shy and unpretentious person who had a sense for the absurd and ironic.

Bourdain, raised in Leonia, a town in New Jersey near New York City, was a good student. He had a strong flair for creative writing and was mainly interested in journalism. As he recalls, the years immediately following his graduation from high school were almost not worth remembering, “a crap existence of confused longing.”

He studied at Vassar College, following his girlfriend and first wife there. He amassed an execrable scholastic record, and dropped out in his final year to work temporarily in a restaurant in Provincetown, Massachusetts. His mother introduced him to the wonders of food, but he never liked her because she had relentlessly shamed and denigrated his beloved father.

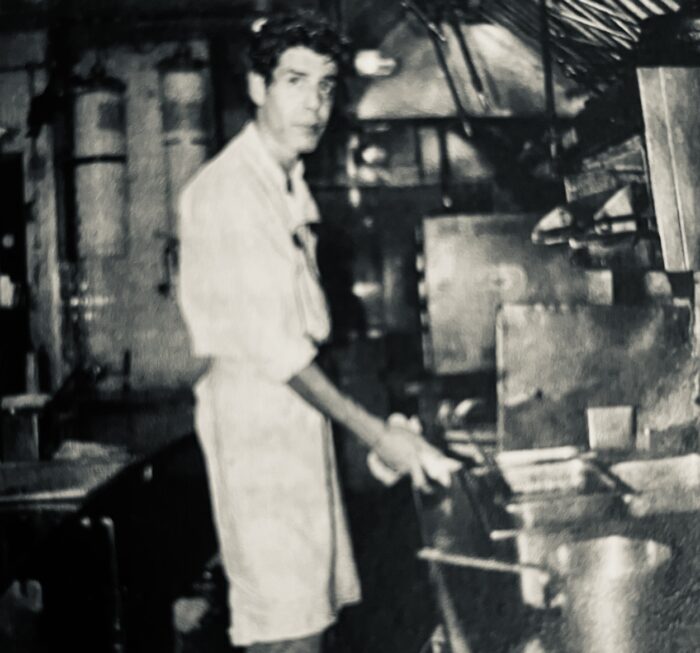

After Vassar, he attended the Culinary Institute of America, after which he toiled in a succession of restaurants. Leerhsen, unfortunately, skips over this phase very quickly.

“Opinions on Tony’s cooking skills vary and, not surprisingly, tend to rise and fall depending on the state of his relationship with the opinion giver,” he writes.

His ambition, though, was to be a writer. He may have been a tortured soul, but he was not a tortured writer, judging by his brilliant article in The New Yorker. A long piece about his days as a restaurant chef, it was submitted to the magazine’s editor, David Remnick, by Gladys Bourdain and Remnick’s wife, her colleague at The New York Times. “I immediately found myself entertained and riveted,” Remnick would later say of Bourdain’s article.

Bourdain lengthened the piece, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Kitchen Underbelly, into a book, and it catapulted him into stardom.

At about that point, Bourdain gravitated into television as the host of a series of cooking shows beginning with Cook’s Tour. Early on, says Leerhsen, he knew what his winning formula would be: “I travel around the world, eat a lot of shit, and basically do whatever the fuck I want.”

Bourdain’s flippant attitude toward management notwithstanding, his work ethic was second to none. As Leerhsen puts it, “His goal from the start was to arrive at every stop on the schedule steeped in the history, high on the literature, and hungry for the signature dish he’d heard about so much.”

Parts Unknown was “the deluxe version” of his previous television shows. In Leerhsen’s estimation, it was “one of the best-looking and most engaging on TV,” and before too long it was “the highest-rated hour on CNN.”

In one of Bourdain’s most watched episodes, he had lunch with U.S. President Barack Obama in a simple restaurant in Hanoi where none of the diners appeared to recognize the heavyweight dignitary in their midst.

Throughout his television career, Bourdain enjoyed his fame, attaching a Google Alert for “Anthony Bourdain” on his cell phone.

Bourdain was twice married, to a Polish American and an Italian, but the love of his life was the Italian starlet Asia Argento, who was allegedly raped by the movie producer Harvey Weinstein. Bourdain scathingly described her as “a cancer that has taken over my whole body and which I can’t get rid of.”

Leerhsen suggests that Bourdain’s fraying relationship with Argento may have caused his suicide. Whatever the reason, Bourdain’s premature death was a severe blow not only to CNN but to foodies everywhere who appreciated his depth of research, his literate approach, and his undiminished gusto for food in all its wonderful and unexpected permutations.