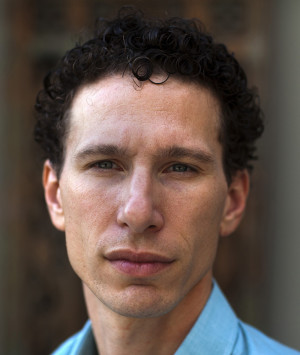

The fifth anniversary of the seminal uprising in Egypt is upon us. On January 25, 2011, thousands of Egyptians from all walks of life converged on Cairo’s Tahrir Square to demand an end to autocracy, a staple in Egypt’s governance. “They weren’t merely trying to overthrow a despicable regime,” writes the American journalist Thanassis Cambanis in Once Upon A Revolution: An Egyptian Story, published by Simon & Schuster. “They were trying to invent a new kind of democracy that would improve on the existing models around the world. They were ambitious idealists.”

After 18 days of non-stop protests, Hosni Mubarak, the long-serving president of Egypt, resigned, having been abandoned by the armed forces and his chief superpower patron, the United States. Mubarak’s resignation, however, did not bring salvation. An interim military council that replaced him was supplanted by a Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohammed Morsi, who became the first democratically-elected president in modern Egyptian history. He, in turn, was deposed by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the minister of defence, in a coup d’etat in 2013 accompanied by massive bloodshed.

Egypt had come full circle.

In Once Upon A A Revolution, a cogent blow-by-blow account of a leaderless people’s revolution, Cambanis examines these momentous chain of events through the eyes of two participants. The first, Moaz Abdelkarim, was a 26-year-old pharmacist who grew up in the Muslim Brotherhood. Basem Kamel, 41, was an architect who represented the revolution’s secular complexion.

As he suggests, one of the prime reasons for the ultimate failure of the revolution was its lack of an overriding objective. Some of the protesters sought top-to-bottom change, a cleansing of the old guard. Others would have been content with a patina of reform: an open political system, an end to emergency rule, a restoration of civil liberties, less corruption and more jobs. Still others, like Mohammed ElBaradei — a diplomat — merely demanded cosmetic modifications from Mubarak.

Apart from a general desire to rid Egypt of Mubarak’s authoritarian regime, the demonstrators had no common vision for the future. As a result, Cambanis says, the army and the Muslim Brotherhood were the chief beneficiaries of Egypt’s revolutionary transition.

Being an astute operator, Mubarak had tried to head off discontent long before it boiled over. As Cambanis correctly points out, he tolerated “some trappings of a democratic society,” permitting a modicum of press freedom and limited criticism of his government.

A grand manipulator, he cowed Egyptians into believing that he stood between stability and chaos, as exemplified by the Muslim Brotherhood or more radical variants of it. In the wake of a jihadist attack on the Temple of Hatshepsut in Luxor in 1997, which claimed the lives of 62 foreign tourists and Egyptians, Mubarak cracked down hard on an Islamist rebellion that threatened to spin out of control. “By 1998, the insurgency was over, and Mubarak enjoyed a rare and final moment of popularity,” Cambanis observes.

With the outbreak of protests on January 25, the Muslim Brotherhood remained on the sidelines, but eventually, it joined the fray, providing know-how, personnel, medicine and food.

In Cambanis’ estimation, “the inchoate revolutionary movement was led by no one, but its vanguard consisted of independent youth and small new factions operating without support of Egypt’s tired old politicians.”

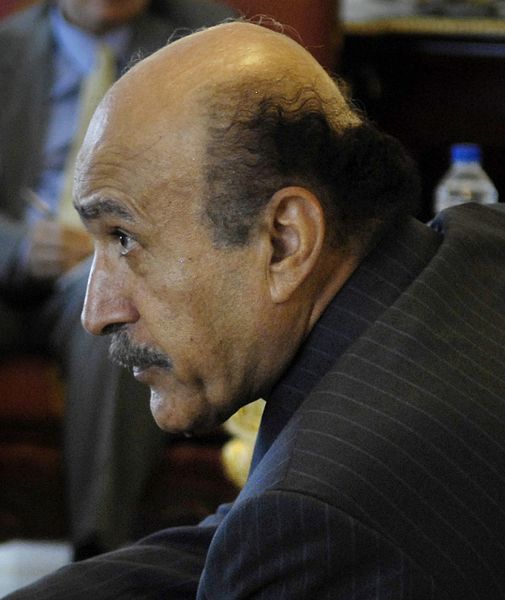

There was no going back after the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, issued a communique on February 10 endorsing the “legitimate demands of the protesters.” It was a transformational moment. Mubarak appeared on television to deliver his final speech, but “the president spoke from a place of deep denial.” The following day, the director of intelligence, Omar Suleiman, formally announced Mubarak’s resignation.

SCAF, with Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi at its head, was now in charge. “Egypt still labored under a dictatorship, one with a greater concentration of power and even less transparency than Mubarak’s,” Cambanis notes.

Tantawi, in bowing to public sentiment, placed Mubarak under house arrest and allowed the criminal justice system to charge him with a plethora of crimes. But at the same time, SCAF imposed greater censorship on the media and extended the state of emergency by one year.

With Mubarak’s overthrow, the position of Egypt’s Christian minority worsened considerably, says Cambanis. Islamic fundamentalists torched three churches in Cairo, causing the deaths of 15 people, and ensuing riots injured 200 Egyptian Christians and Muslims.

In 2012, the Muslim Brotherhood won parliamentary and presidential elections. The new president, Mohammed Morsi, committed one error after another. “Muslim Brothers ignored major issues from the continuing state of emergency to the military trials of civilians, pushing only on matters that would increase their share of power,” writes Cambanis. Worse still, Morsi never attempted to form a unity government, preferring an ideological alliance with the more extreme Salafis, and issuing a decree granting him unlimited dictatorial powers.

One of Morsi’s most egregious mistakes was appointing Sisi defence minister. Formerly director of military intelligence, Sisi was a pious Muslim who seemed to be in alignment with Morsi. But after a bickering coalition of liberals, secularists and nationalists found common ground in opposing Morsi, Sisi turned against the president.

A new political movement, Tammarod, challenged the legitimacy of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. SCAF, meanwhile, began issuing warnings and Sisi declared he would always side with “the people.” In the face of increasing criticism, Morsi “dropped all pretense of moderation,” appointing a Muslim extremist as governor of Luxor and praising Islamic radicals seeking martyrdom. “Questions about Morsi’s competence grew, particularly in military circles,” Cambanis writes. Morsi, however, continued to believe in Sisi’s loyalty.

Looking back, Cambanis ascribes the failure of the revolution to a variety of factors: “Egypt’s revolution was defeated so readily because it wasn’t organized, it wasn’t political enough, and, most fatally, it didn’t have a compelling, constructive idea at its center.”

Lest he be misunderstood, Cambanis places ultimate responsibility on the shoulders of the Egyptian elite: the armed forces, the Muslim Brotherhood and Mubarak’s National Democratic Party, in that order. “They did the damage; they ruined the country. But the revolutionaries are to blame for failing to make a coherent, plausible revolution.”

Saving the remainder of his critique for Sisi, the current president, Cambanis leaves a reader with a disturbing reminder: Sisi, in his first year of power after deposing Morsi, killed and arrested more dissidents/opponents than Mubarak did in almost three decades as president.

Five years on, Egyptian idealists like Moaz Abdelkarim and Basem Kamel must be very disappointed and disillusioned.