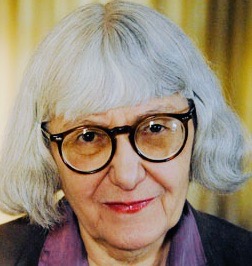

Lucy Dawidowicz was one of the eminent historians of the twentieth century. She was the author of three critically-acclaimed books — The Golden Tradition: Jewish Life and Thought in Eastern Europe (1967), The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945 (1975) and From That Place and Time: A Memoir, 1938-1947 (1989). She was also the first recipient of an American university chair devoted to the study of the Holocaust.

Born as Lucy Schildkret in New York City in 1915, and reared in a Yiddish-speaking socialist home, she was the eldest daughter of Polish Jews who immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s.

As a college student, she dallied with communism, only to turn against it to embrace liberalism. By the mid-1960s, she was a neo-conservative, writing articles for Commentary magazine, which was edited by Norman Podhoretz.

Like the New York intellectuals in his circle — Irving Kristol, Milton Himmelfarb, Midge Decter and Nathan Perlmutter — she questioned the assumption that “intellectual Jewishness and liberal political values were synonymous,” writes Nancy Sinkoff in From Left To Right (Wayne State University Press), an invigorating intellectual biography of Dawidowicz which explores her political journey from communism to conservatism and traces her career as an academic.

Sinkoff, a Rutgers University historian, succinctly describes Dawidowicz as “an American Jew, an East European immigrant daughter, a Polish Jew by choice, and a Jew singed but not consumed by the fires of the Holocaust.”

As Sinkoff explains, Dawidowicz’s life was bookended by World War I and the fall of Soviet communism and buffeted by Nazism and the mass murder of European Jews.

“When she rejected the liberal tilt of American Jewish politics, she did so from within the tradition of Jewish political conservatism deeply informed by her experiences in Europe, her lifelong involvement with Yiddish culture, and her commitment to Jewish cultural autonomy.”

Long associated with the Yiddish Scientific Institute, or YIVO, Dawidowicz lived and studied in Vilna, Poland, from September 1938 until August 1939, a formative period that left a lasting impact on her.

Dawidowicz’s parents, Max and Dora, were financially insecure. When they failed to pay the mortgage on a newly-purchased home in the West Bronx, they were forced to move to a dismal apartment in the dilapidated East Bronx.

At Hunter College, Dawidowicz was an English major and contributed short stories and book reviews to the campus newspaper and literary magazine. She was also a member of the Young Communist League. Unemployed after graduation, she joined the Sholem Aleichem Youth Organization and immersed herself in Yiddish literature.

She broke with communism in 1938, blasting the Bolshevik revolution as “a trick pulled by a gang of crooks, thugs and murderers.”

She enrolled in Columbia University’s graduate school to study English literature, but withdrew two weeks later. Transferring to its history department, she decided to write her MA thesis on the Yiddish press in nineteenth century Britain.

At the urging of an advisor, she applied to YIVO’s graduate program in Vilna, known as the Aspirantur. “When she left New York City of August 10, 1938, (she) travelled against the patterns of modern Jewish migration. She went from west to east, from the New world to Jewish Eastern Europe.”

In Vilna, two major figures, Max Weinreich and Zelig Kalmanovitch, became her intellectual, psychological and personal mentors.

She pursued her MA dissertation at YIVO, but the topic did not “captivate” her, says Sinkoff. Yet her experience as a research fellow shaped Dawidowicz as a historian. “She learned how to conceptualize a viable research project, do the research, and present findings in a systematic and engaging manner.”

Although Weinreich played a key role in her development, Kalmanovitch exerted the greatest influence, unsettling her ideological assumptions and her lingering leftist orientation.

Dawidowicz encountered antisemitism in Vilna, which permeated the most educated sectors of Polish society. To many Polish Catholics, Jews were not regarded as real Poles.

She left Poland on the eve of World War II, transiting through a sea of swastika flags in Berlin en route to Copenhagen, where she boarded a ship bound for New York. For the next six years, she worked with Weinreich, who had been able to leave Europe. Kalmanovitch was not as fortunate, perishing during the Holocaust.

Weinreich worked tirelessly to transplant YIVO in America. “This placed (Dawidowicz) directly at the center of some of the earliest scholarly efforts on U.S. soil to analyze the fate of Jews under German occupation, inform the world of what had befallen them, and begin the process of historicizing what would later be called the ‘khurban’ by Yiddish-speaking Jews and the Holocaust by English speakers.”

By 1943, her relationship with YIVO began to sour, but the reasons are not completely clear. As a result, she returned to Columbia University to complete her post-graduate degree. But this interlude was of short duration. The American Joint Distribution Committee hired her to work as an educational officer among Jewish displaced persons in Germany, where she was employed for 15 months. “Her postwar European sojourn intensified her identification with Europe’s vanished Jewish communities,” says Sinkoff.

One of her tasks was to rummage through YIVO’s library and archives at the Offenbach Archival Depot and to tranship them to New York.

During this time, she married Szymon Dawidowicz, a Polish refugee who would be a YIVO copy editor.

Returning to New York, she worked with the novelist John Hersey on The Wall, a fictional account of the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising.

In the winter of 1949, she started working for the American Jewish Committee’s Information and Research Services Department. This position gave her an institutional home to develop her interests, which ranged from Soviet communism to the role of the Soviet Union in the Middle East.

Around this time, Commentary began publishing her book reviews and commentaries on Jewish issues. And she finally finished her MA, turning in a thesis on Louis Marshall, the president of the American Jewish Committee from 1912 to 1929.

By this point, she considered Stalinist and Nazi totalitarianism as twin antisemitic evils. In accordance with her views, she condemned Julius and Ethel Rosenberg as Soviet spies and lauded their conviction as traitors.

Dawidowicz’s anthology, The Golden Tradition: The Jewish Experience in Eastern Europe, earned her instant acclaim and launched her public career.

The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945 established her as an authority on the Holocaust. In the school of Holocaust historiography, she was an “intentionalist” rather than a “functionalist.” She believed the Holocaust was inevitable, given Hitler’s antisemitic ideology. Functionalists, more persuasively, argued that the Nazi genocide emerged as an evolutionary process due to the exigencies of war with the Soviet Union and the competition between German bureaucracies.

She never wavered from her “intentionalist” perspective, notwithstanding the scathing reviews of some critics, who labelled her approach as amateurish and parochial. Yet Dawidowicz’s focus on German antisemitism as a root cause of the Final Solution was partially vindicated by the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer, who agreed that “Nazi racial antisemitic ideology was the central factor in the development” of the Holocaust.

Dawidowicz wrote The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945 after she was appointed to teach at Stern College and the Wurzweiler School of Social Work at Yeshiva University. At Stern College, she was the Leah and Paul Lewis Professor of Holocaust Studies — the first chair in an American university to specialize in the Shoah. She held that job for five years.

She accepted a U.S. government position as a member of President Jimmy Carter’s Holocaust commission, but was a thorn in its side, as Sinkoff notes. She maintained that the proposed Holocaust museum should be in New York City rather than in Washington, D.C. And she believed that museums of Jewish history celebrating Jewish creativity were more important than museums chronicling the Holocaust.

After William Styron’s novel, Sophie’s Choice, was published, she wrote that Polish Catholic suffering was not representative of the Holocaust. According to Sinkoff, she never forgave Polish Christians for their behavior during the German occupation, whether as collaborators or bystanders.

She was of the opinion that Jewish life in Poland essentially ended after the Polish regime’s antisemitic campaign following the 1967 Six Day War in the Middle East. “Antisemitism was “endemic” to Poland, she wrote in one of her lesser known books, The Holocaust and the Historians.

Dawidowicz defended President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s efforts to save European Jews and rejected the notion that the American Jewish leadership had been indifferent to the plight of Jews under Nazi captivity.

A right-wing Zionist after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, she rejected all public criticism of Israel and claimed that “Peace Now people were motivated by narrow partisan politics.”

A Republican by this juncture, she claimed that the Democratic Party had been hijacked by a New Left agenda that threatened Jewish interests by its tolerance of African American antisemitism and the anti-Zionism of the United Nations.

Unlike liberals, she did not fear the Moral Majority, the Christian fundamentalist organization run by Jerry Falwell, and was certain it would not erode America’s tolerance of religious pluralism.

A year before her death, From That Place and Time: A Memoir, 1938-1947, was published. An ode to the murdered Jews of Vilna and the Yiddish language, it won the National Jewish Book Award. The novelist/Yiddishist Cynthia Ozick praised it as “a great and moving book.”

Dawidowicz died on December 5, 1990 from complications related to cancer. Since her death, Sinkoff points out, the fissures between liberal and conservative American Jews have grown, underscoring the “political polarities and cultural challenges” she anticipated during her lifetime.